Young Van Bibber came up to town in June from Newport to see his lawyer about the preparation of some papers that needed his signature. He found the city very hot and close, and as dreary and as empty as a house that has been shut up for some time while its usual occupants are away in the country.

As he had to wait over for an afternoon train, and as he was down town, he decided to lunch at a French restaurant near Washington Square, where some one had told him you could get particular things particularly well cooked. The tables were set on a terrace with plants and flowers about them, and covered with a tricolored awning. There were no jangling horse-car bells nor dust to disturb him, and almost all the other tables were unoccupied. The waiters leaned against these tables and chatted in a French argot; and a cool breeze blew through the plants and billowed the awning, so that, on the whole, Van Bibber was glad he had come.

There was, beside himself, an old Frenchman scolding over his late breakfast; two young artists with Van Dyke beards, who ordered the most remarkable things in the same French argot that the waiters spoke; and a young lady and a young gentleman at the table next to his own. The young man’s back was toward him, and he could only see the girl when the youth moved to one side. She was very young and very pretty, and she seemed in a most excited state of mind from the tip of her wide-brimmed, pointed French hat to the points of her patent-leather ties. She was strikingly well-bred in appearance, and Van Bibber wondered why she should be dining alone with so young a man.

“It wasn’t my fault,” he heard the youth say earnestly. “How could I know he would be out of town? and anyway it really doesn’t matter. Your cousin is not the only clergyman in the city.”

“Of course not,” said the girl, almost tearfully, “but they’re not my cousins and he is, and that would have made it so much, oh, so very much different. I’m awfully frightened!”

“Runaway couple,” commented Van Bibber. “Most interesting. Read about ‘em often; never seen ‘em. Most interesting.”

He bent his head over an entree, but he could not help hearing what followed, for the young runaways were indifferent to all around them, and though he rattled his knife and fork in a most vulgar manner, they did not heed him nor lower their voices.

“Well, what are you going to do?” said the girl, severely but not unkindly. “It doesn’t seem to me that you are exactly rising to the occasion.”

“Well, I don’t know,” answered the youth, easily. “We’re safe here anyway. Nobody we know ever comes here, and if they did they are out of town now. You go on and eat something, and I’ll get a directory and look up a lot of clergymen’s addresses, and then we can make out a list and drive around in a cab until we find one who has not gone off on his vacation. We ought to be able to catch the Fall River boat back at five this afternoon; then we can go right on to Boston from Fall River to-morrow morning and run down to Narragansett during the day.”

“They’ll never forgive us,” said the girl.

“Oh, well, that’s all right,” exclaimed the young man, cheerfully. “Really, you’re the most uncomfortable young person I ever ran away with. One might think you were going to a funeral. You were willing enough two days ago, and now you don’t help me at all. Are you sorry?” he asked, and then added, “but please don’t say so, even if you are.”

“No, not sorry, exactly,” said the girl; “but, indeed, Ted, it is going to make so much talk. If we only had a girl with us, or if you had a best man, or if we had witnesses, as they do in England, and a parish registry, or something of that sort; or if Cousin Harold had only been at home to do the marrying.”

The young gentleman called Ted did not look, judging from the expression of his shoulders, as if he were having a very good time.

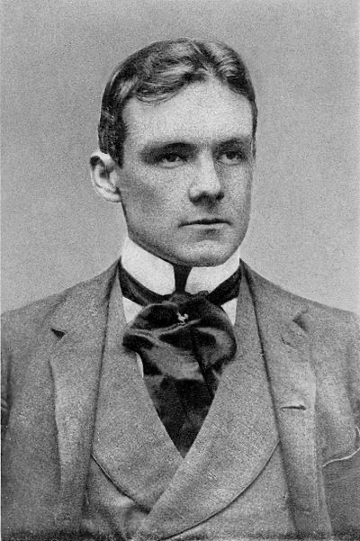

He picked at the food on his plate gloomily, and the girl took out her handkerchief and then put it resolutely back again and smiled at him. The youth called the waiter and told him to bring a directory, and as he turned to give the order Van Bibber recognized him and he recognized Van Bibber. Van Bibber knew him for a very nice boy, of a very good Boston family named Standish, and the younger of two sons. It was the elder who was Van Bibber’s particular friend. The girl saw nothing of this mutual recognition, for she was looking with startled eyes at a hansom that had dashed up the side street and was turning the corner.

“Ted, O Ted!” she gasped. “It’s your brother. There! In that hansom. I saw him perfectly plainly. Oh, how did he find us? What shall we do?”

Ted grew very red and then very white.

“Standish,” said Van Bibber, jumping up and reaching for his hat, “pay this chap for these things, will you, and I’ll get rid of your brother.”

Van Bibber descended the steps lighting a cigar as the elder Standish came up them on a jump.

“Hello, Standish!” shouted the New Yorker. “Wait a minute; where are you going? Why, it seems to rain Standishes to-day! First see your brother; then I see you. What’s on?”

“You’ve seen him?” cried the Boston man, eagerly. “Yes, and where is he? Was she with him? Are they married? Am I in time?”

Van Bibber answered these different questions to the effect that he had seen young Standish and Mrs. Standish not a half an hour before, and that they were just then taking a cab for Jersey City, whence they were to depart for Chicago.

“The driver who brought them here, and who told me where they were, said they could not have left this place by the time I would reach it,” said the elder brother, doubtfully.

“That’s so,” said the driver of the cab, who had listened curiously. “I brought ‘em here not more’n half an hour ago. Just had time to get back to the depot. They can’t have gone long.”

“Yes, but they have,” said Van Bibber. “However, if you get over to Jersey City in time for the 2.30, you can reach Chicago almost as soon as they do. They are going to the Palmer House, they said.”

“Thank you, old fellow,” shouted Standish, jumping back into his hansom. “It’s a terrible business. Pair of young fools. Nobody objected to the marriage, only too young, you know. Ever so much obliged.”

“Don’t mention it,” said Van Bibber, politely.

“Now, then,” said that young man, as he approached the frightened couple trembling on the terrace, “I’ve sent your brother off to Chicago. I do not know why I selected Chicago as a place where one would go on a honeymoon. But I’m not used to lying and I’m not very good at it. Now, if you will introduce me, I’ll see what can be done toward getting you two babes out of the woods.”

Standish said, “Miss Cambridge, this is Mr. Cortlandt Van Bibber, of whom you have heard my brother speak,” and Miss Cambridge said she was very glad to meet Mr. Van Bibber even under such peculiarly trying circumstances.

“Now what you two want to do,” said Van Bibber, addressing them as though they were just about fifteen years old and he were at least forty, “is to give this thing all the publicity you can.”

“What?” chorused the two runaways, in violent protest.

“Certainly,” said Van Bibber. “You were about to make a fatal mistake. You were about to go to some unknown clergyman of an unknown parish, who would have married you in a back room, without a certificate or a witness, just like any eloping farmer’s daughter and lightning-rod agent. Now it’s different with you two. Why you were not married respectably in church I don’t know, and I do not intend to ask, but a kind Providence has sent me to you to see that there is no talk nor scandal, which is such bad form, and which would have got your names into all the papers. I am going to arrange this wedding properly, and you will kindly remain here until I send a carriage for you. Now just rely on me entirely and eat your luncheon in peace. It’s all going to come out right—and allow me to recommend the salad, which is especially good.”

Van Bibber first drove madly to the Little Church Around the Corner, where he told the kind old rector all about it, and arranged to have the church open and the assistant organist in her place, and a district-messenger boy to blow the bellows, punctually at three o’clock. “And now,” he soliloquized, “I must get some names. It doesn’t matter much whether they happen to know the high contracting parties or not, but they must be names that everybody knows. Whoever is in town will be lunching at Delmonico’s, and the men will be at the clubs.” So he first went to the big restaurant, where, as good luck would have it, he found Mrs. “Regy” Van Arnt and Mrs. “Jack” Peabody, and the Misses Brookline, who had run up the Sound for the day on the yacht Minerva of the Boston Yacht Club, and he told them how things were and swore them to secrecy, and told them to bring what men they could pick up.

At the club he pressed four men into service who knew everybody and whom everybody knew, and when they protested that they had not been properly invited and that they only knew the bride and groom by sight, he told them that made no difference, as it was only their names he wanted. Then he sent a messenger boy to get the biggest suit of rooms on the Fall River boat and another one for flowers, and then he put Mrs. “Regy” Van Arnt into a cab and sent her after the bride, and, as best man, he got into another cab and carried off the groom.

“I have acted either as best man or usher forty-two times now,” said Van Bibber, as they drove to the church, “and this is the first time I ever appeared in either capacity in russia-leather shoes and a blue serge yachting suit. But then,” he added, contentedly, “you ought to see the other fellows. One of them is in a striped flannel.”

Mrs. “Regy” and Miss Cambridge wept a great deal on the way up town, but the bride was smiling and happy when she walked up the aisle to meet her prospective husband, who looked exceedingly conscious before the eyes of the men, all of whom he knew by sight or by name, and not one of whom he had ever met before. But they all shook hands after it was over, and the assistant organist played the Wedding March, and one of the club men insisted in pulling a cheerful and jerky peal on the church bell in the absence of the janitor, and then Van Bibber hurled an old shoe and a handful of rice—which he had thoughtfully collected from the chef at the club—after them as they drove off to the boat.

“Now,” said Van Bibber, with a proud sigh of relief and satisfaction, “I will send that to the papers, and when it is printed to-morrow it will read like one of the most orthodox and one of the smartest weddings of the season. And yet I can’t help thinking—”

“Well?” said Mrs. “Regy,” as he paused doubtfully.

“Well, I can’t help thinking,” continued Van Bibber, “of Standish’s older brother racing around Chicago with the thermometer at 102 in the shade. I wish I had only sent him to Jersey City. It just shows,” he added, mournfully, “that when a man is not practised in lying, he should leave it alone.”