Once upon a time there lived an old man who had three sons. The two elder sons were well-favoured young men who liked to wear fine clothes and were thrifty husbandmen, but the youngest, Ivan the Fool, was none of those things. He spent most of his time at home sitting on the stove ledge and only going out to gather mushrooms in the forest.

When the time came for the old man to die, he called his three sons to his side and said to them:

“When I die, you must come to my grave every night for three nights and bring me some bread to eat.”

The old man died and was buried, and that night the time came for the eldest brother to go to his grave. But he was too lazy or else too frightened to go, and he said to Ivan the Fool:

“If you will only go in my stead to our father’s grave tonight, Ivan, I shall buy you a honey-cake.”

Ivan readily agreed, took some bread and went to his father’s grave. He sat down by the grave and waited to see what would happen. On the stroke of midnight the earth crumbled apart and the old father rose out of his grave and said:

“Who is there? Is it you, my first-born? Tell me how everything fares in Rus: are the dogs barking, the wolves howling or my child weeping?”

And Ivan replied:

“It is I, your son, Father. And all is quiet in Rus.”

Then the father ate his fill of the bread Ivan had brought and lay down in his grave again. As for Ivan, he went home, stopping to gather some mushrooms on the way.

When he reached home, his eldest brother asked:

“Did you see our father?”

“Yes, I did,” Ivan replied.

“Did he eat of the bread you brought?”

“Yes. He ate till he could eat no more.”

Another day passed by, and it was the second brother’s turn to go to the grave. But he was too lazy or else too frightened to go, and he said to Ivan:

“If only you go in my stead, Ivan, I shall make you a pair of bast shoes.”

“Very well,” said Ivan, “I shall go.”

He took some bread, went to his father’s grave and sat there waiting. On the stroke of midnight the earth crumbled apart and the old father rose out of the grave and said:

“Who is there? Is it you, my second-born? Tell me how everything fares in Rus: are the dogs barking, the wolves howling or my child weeping?”

And Ivan replied:

“It is I, your son, Father. And all is quiet in Rus.”

Then the father ate his fill of the bread Ivan had brought and lay down in his grave again. And Ivan went home, stopping to gather some mushrooms on the way. He reached home and his second brother asked him:

“Did our father eat of the bread you brought?”

“Yes,” Ivan replied. “He ate till he could eat no more.”

On the third night it was Ivan’s turn to go to the grave and he said to his brothers:

“For two nights I have gone to our father’s grave. Now it is your turn to go and I will stay home and rest.”

“Oh, no,” the brothers replied. “You must go again, Ivan, for you are used to it.”

“Very well,” Ivan agreed, “I shall go.”

He took some bread and went to the grave, and on the stroke of midnight the earth crumbled apart and the old father rose out of the grave.

“Who is there?” said he. “Is it you, Ivan, my third-born? Tell me how everything fares in Rus: are the dogs barking, the wolves howling or my child weeping?”

And Ivan replied:

“It is I, your son Ivan, Father. And all is quiet in Rus.”

The father ate his fill of the bread Ivan had brought and said to him:

“You were the only one to obey my command, Ivan. You were not afraid to come to my grave for three nights. Now you must go out into the open field and shout: ‘Chestnut-Grey, hear and obey! I call thee nigh to do or die!’ When the horse appears before you, climb into his right ear and come out of his left, and you will turn into as comely a lad as ever was seen. Then mount the horse and go where you will.”

Ivan took the bridle his father gave him, thanked him and went home, stopping to gather some mushrooms on the way. He reached home and his brothers asked him: “Did you see our father, Ivan?”

“Yes, I did,” Ivan replied. “Did he eat of the bread you brought?”

“Yes, he ate till he could eat no more and he bade me not to go to his grave any more.”

Now, at this very time the Tsar had a call sounded abroad for all handsome, unmarried young men to gather at court. The Tsar’s daughter, Tsarevna Lovely, had ordered a castle of twelve pillars and twelve rows of oak logs to be built for herself. And there she meant to sit at the window of the top chamber and await the one who would leap on his steed as high as her window and place a kiss on her lips.

To him who succeeded, whether of high or of low birth, the Tsar would give Tsarevna Lovely, his daughter, in marriage and half his tsardom besides.

News of this came to the ears of Ivan’s brothers, who agreed between them to try their luck.

They gave a feed of oats to their goodly steeds and led them from the stables, and themselves put on their best apparel and combed down their curly locks. And Ivan, who was sitting on the stove ledge behind the chimney, said to them:

“Take me with you, my brothers, and let me try my luck, too.”

“You silly sit-on-the-stove!” laughed they. “You will only be mocked at if you go with us. Better go and hunt for mushrooms in the forest.”

The brothers mounted their goodly steeds, cocked their hats, gave a whistle and a whoop and galloped off down the road in a cloud of dust. And Ivan took the bridle his father had given him, went out into the open field and shouted as his father had told him:

“Chestnut-Grey, hear and obey! I call thee nigh to do or die!” And, lo and behold! a charger came running towards him. The earth shook under his hoofs, his nostrils spurted flame, and clouds of smoke poured from his ears. The charger galloped up to Ivan, stood stockstill and said: “What is your wish, Ivan?”

Ivan stroked the steed’s neck, bridled him, climbed into his right ear and came out through his left. And lo! he was turned into a youth as fair as the sky at dawn, the handsomest youth that ever was born.

He got up on Chestnut-Grey’s back and set off for the Tsar’s palace.

On went Chestnut-Grey with a snort and a neigh, passing mountain and dale with a swish of his tail, skirting houses and trees as quick as the breeze.

When Ivan arrived at court, the palace grounds were teeming with people. There stood the castle of twelve pillars and twelve rows of oak logs, and in its highest attic, at the window of her chamber, sat Tsarevna Lovely.

The Tsar stepped out on the porch and said:

“He from amongst you, good youths, who leaps up on his steed as high as yon window and places a kiss upon my daughter’s lips, shall have her in marriage and half my tsardom besides.”

One after another the wooers of Tsarevna Lovely rode up and pranced and leaped, but, alas, the window was out of their reach.

Ivan’s two brothers tried with the rest, but with no better success.

When Ivan’s turn came, he sent Chestnut-Grey at a gallop and with a whoop and a shout leapt up as high as the highest row of logs but two. On he came again and leapt up as high as the highest row but one. One more chance was left him, and he pranced and whirled Chestnut-Grey round and round till the steed chafed and fumed. Then,

bounding like fire past her window, he took a great leap and placed a kiss on the honey-sweet lips of Tsarevna Lovely. And the Tsarevna struck his brow with her signet-ring and left her seal on him.

The people roared: “Hold him! Stop him!” but Ivan and his steed were gone in a cloud of dust.

Off they galloped to the open field, and Ivan climbed into

Chestnut-Grey’s left ear and came out through his right, and lo! he was changed to his proper shape again. Then he let Chestnut-Grey run free and himself went home, stopping to gather some mushrooms on the way. He came into the house, bound his forehead with a rag, climbed up on the stove ledge and lay there as before.

By and by his brothers arrived and began telling him where they had been and what they had seen.

“Many were the wooers of the Tsarevna, and handsome, too,” they said. “But one there was who outshone them all. He leapt up on his fiery steed to the Tsarevna’s window and he kissed her lips. We saw him come, but we did not see him go.”

Said Ivan from his perch behind the chimney:

“Perhaps it was me you saw.”

His brothers flew into a temper and said:

“Stop your silly talk, fool! Sit there on your stove and eat your mushrooms.”

Then Ivan untied the rag that covered the seal from the Tsarevna’s signet-ring and at once a bright glow lit up the hut. The brothers were frightened and cried:

“What are you doing, fool? You’ll burn down the house!”

The next day the Tsar held a feast to which he summoned all his subjects, boyars and nobles and common folk, rich and poor, young and old.

Ivan’s brothers, too, prepared to attend the feast.

“Take me with you, my brothers,” Ivan begged.

“What?” they laughed. “You will only be mocked at by all. Stay here on your stove and eat your mushrooms.”

The brothers then mounted their goodly steeds and rode away, and Ivan followed them on foot. He came to the Tsar’s palace and seated himself in a far corner. Tsarevna Lovely now began to make the round of all the guests. She offered each a drink from the cup of mead she carried and she looked at their brows to see if her seal were there.

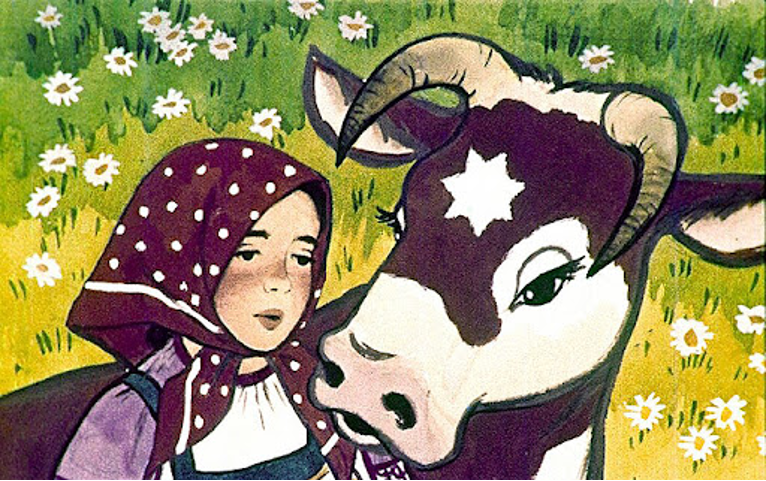

She made the round of all the guests except Ivan, and when she approached him her heart sank. He was all smutted with soot and his hair stood on end.

Said Tsarevna Lovely:

“Who are you? Where do you come from? And why is your brow bound with a rag?”

“I hurt myself in falling,” Ivan replied.

The Tsarevna unwound the rag and a bright glow at once lit up the palace.

“That is my seal!” she cried. “Here is my betrothed!”

The Tsar came up to Ivan, looked at him and said:

“Oh, no, Tsarevna Lovely! This cannot be your betrothed! He is all sooty and very plain.”

Said Ivan to the Tsar:

“Allow me to wash my face, Tsar.”

The Tsar gave him leave to do so, and Ivan came out into the courtyard and shouted as his father had taught him to:

“Chestnut-Grey, hear and obey! I call thee nigh to do or die!”

And lo and behold! Chestnut-Grey came galloping towards him.

The earth shook under his hoofs, his nostrils spurted flame, and clouds of smoke poured from his ears. Ivan climbed into his right ear and came out through his left and was turned into a youth as fair as the sky at dawn, the handsomest youth that ever was born. All the people in the palace gave a great gasp when they saw him.

No words were wasted after that.

Ivan married Tsarevna Lovely, and a merry feast was held to celebrate their wedding.