by Richard Harding Davis

Young Latimer stood on one of the lower steps of the hall stairs, leaning with one hand on the broad railing and smiling down at her. She had followed him from the drawing-room and had stopped at the entrance, drawing the curtains behind her, and making, unconsciously, a dark background for her head and figure. He thought he had never seen her look more beautiful, nor that cold, fine air of thorough breeding about her which was her greatest beauty to him, more strongly in evidence.

“Well, sir,” she said, “why don’t you go?”

He shifted his position slightly and leaned more comfortably upon the railing, as though he intended to discuss it with her at some length.

“How can I go,” he said, argumentatively, “with you standing there—looking like that?”

“I really believe,” the girl said, slowly, “that he is afraid; yes, he is afraid. And you always said,” she added, turning to him, “you were so brave.”

“Oh, I am sure I never said that,” exclaimed the young man, calmly. “I may be brave, in fact, I am quite brave, but I never said I was. Some one must have told you.”

“Yes, he is afraid,” she said, nodding her head to the tall clock across the hall, “he is temporizing and trying to save time. And afraid of a man, too, and such a good man who would not hurt any one.”

“You know a bishop is always a very difficult sort of a person,” he said, “and when he happens to be your father, the combination is just a bit awful. Isn’t it now? And especially when one means to ask him for his daughter. You know it isn’t like asking him to let one smoke in his study.”

“If I loved a girl,” she said, shaking her head and smiling up at him, “I wouldn’t be afraid of the whole world; that’s what they say in books, isn’t it? I would be so bold and happy.”

“Oh, well, I’m bold enough,” said the young man, easily; “if I had not been, I never would have asked you to marry me; and I’m happy enough—that’s because I did ask you. But what if he says no,” continued the youth; “what if he says he has greater ambitions for you, just as they say in books, too? What will you do? Will you run away with me? I can borrow a coach just as they used to do, and we can drive off through the Park and be married, and come back and ask his blessing on our knees—unless he should overtake us on the elevated.”

“That,” said the girl, decidedly, “is flippant, and I’m going to leave you. I never thought to marry a man who would be frightened at the very first. I am greatly disappointed.”

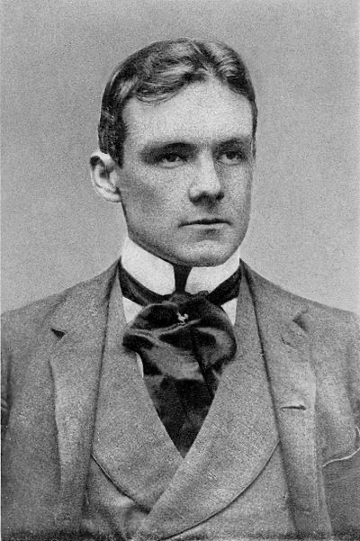

She stepped back into the drawing-room and pulled the curtains to behind her, and then opened them again and whispered, “Please don’t be long,” and disappeared. He waited, smiling, to see if she would make another appearance, but she did not, and he heard her touch the keys of the piano at the other end of the drawing-room. And so, still smiling and with her last words sounding in his ears, he walked slowly up the stairs and knocked at the door of the bishop’s study. The bishop’s room was not ecclesiastic in its character. It looked much like the room of any man of any calling who cared for his books and to have pictures about him, and copies of the beautiful things he had seen on his travels. There were pictures of the Virgin and the Child, but they were those that are seen in almost any house, and there were etchings and plaster casts, and there were hundreds of books, and dark red curtains, and an open fire that lit up the pots of brass with ferns in them, and the blue and white plaques on the top of the bookcase. The bishop sat before his writing-table, with one hand shading his eyes from the light of a red-covered lamp, and looked up and smiled pleasantly and nodded as the young man entered. He had a very strong face, with white hair hanging at the side, but was still a young man for one in such a high office. He was a man interested in many things, who could talk to men of any profession or to the mere man of pleasure, and could interest them in what he said, and force their respect and liking. And he was very good, and had, they said, seen much trouble.

“I am afraid I interrupted you,” said the young man, tentatively.

“No, I have interrupted myself,” replied the bishop. “I don’t seem to make this clear to myself,” he said, touching the paper in front of him, “and so I very much doubt if I am going to make it clear to any one else. However,” he added, smiling, as he pushed the manuscript to one side, “we are not going to talk about that now. What have you to tell me that is new?”

The younger man glanced up quickly at this, but the bishop’s face showed that his words had had no ulterior meaning, and that he suspected nothing more serious to come than the gossip of the clubs or a report of the local political fight in which he was keenly interested, or on their mission on the East Side. But it seemed an opportunity to Latimer.

“I have something new to tell you,” he said, gravely, and with his eyes turned toward the open fire, “and I don’t know how to do it exactly. I mean I don’t just know how it is generally done or how to tell it best.” He hesitated and leaned forward, with his hands locked in front of him, and his elbows resting on his knees. He was not in the least frightened. The bishop had listened to many strange stories, to many confessions, in this same study, and had learned to take them as a matter of course; but to-night something in the manner of the young man before him made him stir uneasily, and he waited for him to disclose the object of his visit with some impatience.

“I will suppose, sir,” said young Latimer, finally, “that you know me rather well—I mean you know who my people are, and what I am doing here in New York, and who my friends are, and what my work amounts to. You have let me see a great deal of you, and I have appreciated your doing so very much; to so young a man as myself it has been a great compliment, and it has been of great benefit to me. I know that better than any one else. I say this because unless you had shown me this confidence it would have been almost impossible for me to say to you what I am going to say now. But you have allowed me to come here frequently, and to see you and talk with you here in your study, and to see even more of your daughter. Of course, sir, you did not suppose that I came here only to see you. I came here because I found that, if I did not see Miss Ellen for a day, that that day was wasted, and that I spent it uneasily and discontentedly, and the necessity of seeing her even more frequently has grown so great that I cannot come here as often as I seem to want to come unless I am engaged to her, unless I come as her husband that is to be.” The young man had been speaking very slowly and picking his words, but now he raised his head and ran on quickly.

“I have spoken to her and told her how I love her, and she has told me that she loves me, and that if you will not oppose us, will marry me. That is the news I have to tell you, sir. I don’t know but that I might have told it differently, but that is it. I need not urge on you my position and all that, because I do not think that weighs with you; but I do tell you that I love Ellen so dearly that, though I am not worthy of her, of course, I have no other pleasure than to give her pleasure and to try to make her happy. I have the power to do it; but what is much more, I have the wish to do it; it is all I think of now, and all that I can ever think of. What she thinks of me you must ask her; but what she is to me neither she can tell you nor do I believe that I myself could make you understand.” The young man’s face was flushed and eager, and as he finished speaking he raised his head and watched the bishop’s countenance anxiously. But the older man’s face was hidden by his hand as he leaned with his elbow on his writing-table. His other hand was playing with a pen, and when he began to speak, which he did after a long pause, he still turned it between his fingers and looked down at it.

“I suppose,” he said, as softly as though he were speaking to himself, “that I should have known this; I suppose that I should have been better prepared to hear it. But it is one of those things which men put off—I mean those men who have children, put off—as they do making their wills, as something that is in the future and that may be shirked until it comes. We seem to think that our daughters will live with us always, just as we expect to live on ourselves until death comes one day and startles us and finds us unprepared.” He took down his hand and smiled gravely at the younger man with an evident effort, and said, “I did not mean to speak so gloomily, but you see my point of view must be different from yours. And she says she loves you, does she?” he added, gently.

Young Latimer bowed his head and murmured something inarticulately in reply, and then held his head erect again and waited, still watching the bishop’s face.

“I think she might have told me,” said the older man; “but then I suppose this is the better way. I am young enough to understand that the old order changes, that the customs of my father’s time differ from those of to-day. And there is no alternative, I suppose,” he said, shaking his head. “I am stopped and told to deliver, and have no choice. I will get used to it in time,” he went on, “but it seems very hard now. Fathers are selfish, I imagine, but she is all I have.”

Young Latimer looked gravely into the fire and wondered how long it would last. He could just hear the piano from below, and he was anxious to return to her. And at the same time he was drawn toward the older man before him, and felt rather guilty, as though he really were robbing him. But at the bishop’s next words he gave up any thought of a speedy release, and settled himself in his chair.

“We are still to have a long talk,” said the bishop. “There are many things I must know, and of which I am sure you will inform me freely. I believe there are some who consider me hard, and even narrow on different points, but I do not think you will find me so, at least let us hope not. I must confess that for a moment I almost hoped that you might not be able to answer the questions I must ask you, but it was only for a moment. I am only too sure you will not be found wanting, and that the conclusion of our talk will satisfy us both. Yes, I am confident of that.”

His manner changed, nevertheless, and Latimer saw that he was now facing a judge and not a plaintiff who had been robbed, and that he was in turn the defendant. And still he was in no way frightened.

“I like you,” the bishop said, “I like you very much. As you say yourself, I have seen a great deal of you, because I have enjoyed your society, and your views and talk were good and young and fresh, and did me good. You have served to keep me in touch with the outside world, a world of which I used to know at one time a great deal. I know your people and I know you, I think, and many people have spoken to me of you. I see why now. They, no doubt, understood what was coming better than myself, and were meaning to reassure me concerning you. And they said nothing but what was good of you. But there are certain things of which no one can know but yourself, and concerning which no other person, save myself, has a right to question you. You have promised very fairly for my daughter’s future; you have suggested more than you have said, but I understood. You can give her many pleasures which I have not been able to afford; she can get from you the means of seeing more of this world in which she lives, of meeting more people, and of indulging in her charities, or in her extravagances, for that matter, as she wishes. I have no fear of her bodily comfort; her life, as far as that is concerned, will be easier and broader, and with more power for good. Her future, as I say, as you say also, is assured; but I want to ask you this,” the bishop leaned forward and watched the young man anxiously, “you can protect her in the future, but can you assure me that you can protect her from the past?”

Young Latimer raised his eyes calmly and said, “I don’t think I quite understand.”

“I have perfect confidence, I say,” returned the bishop, “in you as far as your treatment of Ellen is concerned in the future. You love her and you would do everything to make the life of the woman you love a happy one; but this is it. Can you assure me that there is nothing in the past that may reach forward later and touch my daughter through you—no ugly story, no oats that have been sowed, and no boomerang that you have thrown wantonly and that has not returned—but which may return?”

“I think I understand you now, sir,” said the young man, quietly. “I have lived,” he began, “as other men of my sort have lived. You know what that is, for you must have seen it about you at college, and after that before you entered the Church. I judge so from your friends, who were your friends then, I understand. You know how they lived. I never went in for dissipation, if you mean that, because it never attracted me. I am afraid I kept out of it not so much out of respect for others as for respect for myself. I found my self-respect was a very good thing to keep, and I rather preferred keeping it and losing several pleasures that other men managed to enjoy, apparently with free consciences. I confess I used to rather envy them. It is no particular virtue on my part; the thing struck me as rather more vulgar than wicked, and so I have had no wild oats to speak of; and no woman, if that is what you mean, can write an anonymous letter, and no man can tell you a story about me that he could not tell in my presence.”

There was something in the way the young man spoke which would have amply satisfied the outsider, had he been present; but the bishop’s eyes were still unrelaxed and anxious. He made an impatient motion with his hand.

“I know you too well, I hope,” he said, “to think of doubting your attitude in that particular. I know you are a gentleman, that is enough for that; but there is something beyond these more common evils. You see, I am terribly in earnest over this—you may think unjustly so, considering how well I know you, but this child is my only child. If her mother had lived, my responsibility would have been less great; but, as it is, God has left her here alone to me in my hands. I do not think He intended my duty should end when I had fed and clothed her, and taught her to read and write. I do not think He meant that I should only act as her guardian until the first man she fancied fancied her. I must look to her happiness not only now when she is with me, but I must assure myself of it when she leaves my roof. These common sins of youth I acquit you of. Such things are beneath you, I believe, and I did not even consider them. But there are other toils in which men become involved, other evils or misfortunes which exist, and which threaten all men who are young and free and attractive in many ways to women, as well as men. You have lived the life of the young man of this day. You have reached a place in your profession when you can afford to rest and marry and assume the responsibilities of marriage. You look forward to a life of content and peace and honorable ambition—a life, with your wife at your side, which is to last forty or fifty years. You consider where you will be twenty years from now, at what point of your career you may become a judge or give up practise; your perspective is unlimited; you even think of the college to which you may send your son. It is a long, quiet future that you are looking forward to, and you choose my daughter as the companion for that future, as the one woman with whom you could live content for that length of time. And it is in that spirit that you come to me tonight and that you ask me for my daughter. Now I am going to ask you one question, and as you answer that I will tell you whether or not you can have Ellen for your wife. You look forward, as I say, to many years of life, and you have chosen her as best suited to live that period with you; but I ask you this, and I demand that you answer me truthfully, and that you remember that you are speaking to her father. Imagine that I had the power to tell you, or rather that some superhuman agent could convince you, that you had but a month to live, and that for what you did in that month you would not be held responsible either by any moral law or any law made by man, and that your life hereafter would not be influenced by your conduct in that month, would you spend it, I ask you—and on your answer depends mine—would you spend those thirty days, with death at the end, with my daughter, or with some other woman of whom I know nothing?”

Latimer sat for some time silent, until indeed, his silence assumed such a significance that he raised his head impatiently and said with a motion of the hand, “I mean to answer you in a minute; I want to be sure that I understand.”

The bishop bowed his head in assent, and for a still longer period the men sat motionless. The clock in the corner seemed to tick more loudly, and the dead coals dropping in the grate had a sharp, aggressive sound. The notes of the piano that had risen from the room below had ceased.

“If I understand you,” said Latimer, finally, and his voice and his face as he raised it were hard and aggressive, “you are stating a purely hypothetical case. You wish to try me by conditions which do not exist, which cannot exist. What justice is there, what right is there, in asking me to say how I would act under circumstances which are impossible, which lie beyond the limit of human experience? You cannot judge a man by what he would do if he were suddenly robbed of all his mental and moral training and of the habit of years. I am not admitting, understand me, that if the conditions which you suggest did exist that I would do one whit differently from what I will do if they remain as they are. I am merely denying your right to put such a question to me at all. You might just as well judge the shipwrecked sailors on a raft who eat each other’s flesh as you would judge a sane, healthy man who did such a thing in his own home. Are you going to condemn men who are ice-locked at the North Pole, or buried in the heart of Africa, and who have given up all thought of return and are half mad and wholly without hope, as you would judge ourselves? Are they to be weighed and balanced as you and I are, sitting here within the sound of the cabs outside and with a bake-shop around the corner? What you propose could not exist, could never happen. I could never be placed where I should have to make such a choice, and you have no right to ask me what I would do or how I would act under conditions that are superhuman—you used the word yourself—where all that I have held to be good and just and true would be obliterated. I would be unworthy of myself, I would be unworthy of your daughter, if I considered such a state of things for a moment, or if I placed my hopes of marrying her on the outcome of such a test, and so, sir,” said the young man, throwing back his head, “I must refuse to answer you.”

The bishop lowered his hand from before his eyes and sank back wearily into his chair. “You have answered me,” he said.

“You have no right to say that,” cried the young man, springing to his feet. “You have no right to suppose anything or to draw any conclusions. I have not answered you.” He stood with his head and shoulders thrown back, and with his hands resting on his hips and with the fingers working nervously at his waist.

“What you have said,” replied the bishop, in a voice that had changed strangely, and which was inexpressibly sad and gentle, “is merely a curtain of words to cover up your true feeling. It would have been so easy to have said, ‘For thirty days or for life Ellen is the only woman who has the power to make me happy.’ You see that would have answered me and satisfied me. But you did not say that,” he added, quickly, as the young man made a movement as if to speak.

“Well, and suppose this other woman did exist, what then?” demanded Latimer. “The conditions you suggest are impossible; you must, you will surely, sir, admit that.”

“I do not know,” replied the bishop, sadly; “I do not know. It may happen that whatever obstacle there has been which has kept you from her may be removed. It may be that she has married, it may be that she has fallen so low that you cannot marry her. But if you have loved her once, you may love her again; whatever it was that separated you in the past, that separates you now, that makes you prefer my daughter to her, may come to an end when you are married, when it will be too late, and when only trouble can come of it, and Ellen would bear that trouble. Can I risk that?”

“But I tell you it is impossible,” cried the young man. “The woman is beyond the love of any man, at least such a man as I am, or try to be.”

“Do you mean,” asked the bishop, gently, and with an eager look of hope, “that she is dead?”

Latimer faced the father for some seconds in silence. Then he raised his head slowly. “No,” he said, “I do not mean she is dead. No, she is not dead.”

Again the bishop moved back wearily into his chair. “You mean then,” he said, “perhaps, that she is a married woman?” Latimer pressed his lips together at first as though he would not answer, and then raised his eyes coldly. “Perhaps,” he said.

The older man had held up his hand as if to signify that what he was about to say should be listened to without interruption, when a sharp turning of the lock of the door caused both father and the suitor to start. Then they turned and looked at each other with anxious inquiry and with much concern, for they recognized for the first time that their voices had been loud. The older man stepped quickly across the floor, but before he reached the middle of the room the door opened from the outside, and his daughter stood in the door-way, with her head held down and her eyes looking at the floor.

“Ellen!” exclaimed the father, in a voice of pain and the deepest pity.

The girl moved toward the place from where his voice came, without raising her eyes, and when she reached him put her arms about him and hid her face on his shoulder. She moved as though she were tired, as though she were exhausted by some heavy work.

“My child,” said the bishop, gently, “were you listening?” There was no reproach in his voice; it was simply full of pity and concern.

“I thought,” whispered the girl, brokenly, “that he would be frightened; I wanted to hear what he would say. I thought I could laugh at him for it afterward. I did it for a joke. I thought—” She stopped with a little gasping sob that she tried to hide, and for a moment held herself erect and then sank back again into her father’s arms with her head upon his breast.

Latimer started forward, holding out his arms to her. “Ellen,” he said, “surely, Ellen, you are not against me. You see how preposterous it is, how unjust it is to me. You cannot mean—”

The girl raised her head and shrugged her shoulders slightly as though she were cold. “Father,” she said, wearily, “ask him to go away. Why does he stay? Ask him to go away.”

Latimer stopped and took a step back as though some one had struck him, and then stood silent with his face flushed and his eyes flashing. It was not in answer to anything that they said that he spoke, but to their attitude and what it suggested. “You stand there,” he began, “you two stand there as though I were something unclean, as though I had committed some crime. You look at me as though I were on trial for murder or worse. Both of you together against me. What have I done? What difference is there? You loved me a half-hour ago, Ellen; you said you did. I know you loved me; and you, sir,” he added, more quietly, “treated me like a friend. Has anything come since then to change me or you? Be fair to me, be sensible. What is the use of this? It is a silly, needless, horrible mistake. You know I love you, Ellen; love you better than all the world. I don’t have to tell you that; you know it, you can see and feel it. It does not need to be said; words can’t make it any truer. You have confused yourselves and stultified yourselves with this trick, this test by hypothetical conditions, by considering what is not real or possible. It is simple enough; it is plain enough. You know I love you, Ellen, and you only, and that is all there is to it, and all that there is of any consequence in the world to me. The matter stops there; that is all there is for you to consider. Answer me, Ellen, speak to me. Tell me that you believe me.”

He stopped and moved a step toward her, but as he did so, the girl, still without looking up, drew herself nearer to her father and shrank more closely into his arms; but the father’s face was troubled and doubtful, and he regarded the younger man with a look of the most anxious scrutiny. Latimer did not regard this. Their hands were raised against him as far as he could understand, and he broke forth again proudly, and with a defiant indignation:

“What right have you to judge me?” he began; “what do you know of what I have suffered, and endured, and overcome? How can you know what I have had to give up and put away from me? It’s easy enough for you to draw your skirts around you, but what can a woman bred as you have been bred know of what I’ve had to fight against and keep under and cut away? It was an easy, beautiful idyl to you; your love came to you only when it should have come, and for a man who was good and worthy, and distinctly eligible—I don’t mean that; forgive me, Ellen, but you drive me beside myself. But he is good and he believes himself worthy, and I say that myself before you both. But I am only worthy and only good because of that other love that I put away when it became a crime, when it became impossible. Do you know what it cost me? Do you know what it meant to me, and what I went through, and how I suffered? Do you know who this other woman is whom you are insulting with your doubts and guesses in the dark? Can’t you spare her? Am I not enough? Perhaps it was easy for her, too; perhaps her silence cost her nothing; perhaps she did not suffer and has nothing but happiness and content to look forward to for the rest of her life; and I tell you that it is because we did put it away, and kill it, and not give way to it that I am whatever I am to-day; whatever good there is in me is due to that temptation and to the fact that I beat it and overcame it and kept myself honest and clean. And when I met you and learned to know you I believed in my heart that God had sent you to me that I might know what it was to love a woman whom I could marry and who could be my wife; that you were the reward for my having overcome temptation and the sign that I had done well. And now you throw me over and put me aside as though I were something low and unworthy, because of this temptation, because of this very thing that has made me know myself and my own strength and that has kept me up for you.”

As the young man had been speaking, the bishop’s eyes had never left his face, and as he finished, the face of the priest grew clearer and decided, and calmly exultant. And as Latimer ceased he bent his head above his daughter’s, and said in a voice that seemed to speak with more than human inspiration. “My child,” he said, “if God had given me a son I should have been proud if he could have spoken as this young man has done.”

But the woman only said, “Let him go to her.”

“Ellen, oh, Ellen!” cried the father.

He drew back from the girl in his arms and looked anxiously and feelingly at her lover. “How could you, Ellen,” he said, “how could you?” He was watching the young man’s face with eyes full of sympathy and concern. “How little you know him,” he said, “how little you understand. He will not do that,” he added quickly, but looking questioningly at Latimer and speaking in a tone almost of command. “He will not undo all that he has done; I know him better than that.” But Latimer made no answer, and for a moment the two men stood watching each other and questioning each other with their eyes. Then Latimer turned, and without again so much as glancing at the girl walked steadily to the door and left the room. He passed on slowly down the stairs and out into the night, and paused upon the top of the steps leading to the street. Below him lay the avenue with its double line of lights stretching off in two long perspectives. The lamps of hundreds of cabs and carriages flashed as they advanced toward him and shone for a moment at the turnings of the cross-streets, and from either side came the ceaseless rush and murmur, and over all hung the strange mystery that covers a great city at night. Latimer’s rooms lay to the south, but he stood looking toward a spot to the north with a reckless, harassed look in his face that had not been there for many months. He stood so for a minute, and then gave a short shrug of disgust at his momentary doubt and ran quickly down the steps. “No,” he said, “if it were for a month, yes; but it is to be for many years, many more long years.” And turning his back resolutely to the north he went slowly home.