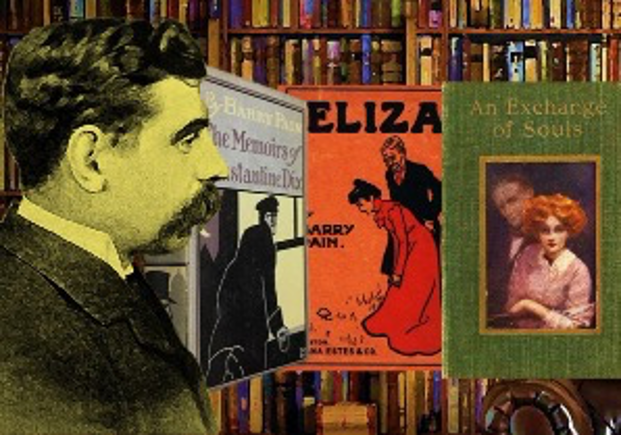

THE DIARY OF A GOD

By Barry Pain

During the week there had been several thunderstorms. It was after the last of these, on a cool Saturday evening, that he was found at the top of the hill by a shepherd. His speech was incoherent and disconnected; he gave his name correctly, but could or would add no account of himself. He was wet through, and sat there pulling a sprig of heather to pieces. The shepherd afterwards said that he had great difficulty in persuading him to come down, and that he talked much nonsense. In the path at the foot of the hill he was recognised by some people from the farmhouse where he was lodging, and was taken back there. They had, indeed, gone out to look for him. He was subsequently removed to an asylum, and died insane a few months later.

*****

Two years afterwards, when the furniture of the farmhouse came to be sold by auction, there was found in a little cupboard in the bedroom which he had occupied an ordinary penny exercise-book. This was partly filled, in a beautiful and very regular handwriting, with what seems to have been something in the nature of a diary, and the following are extracts from it:

June 1st.—It is absolutely essential to be quiet. I am beginning life again, and in quite a different way, and on quite a different scale, and I cannot make the break suddenly. I must have a pause of a few weeks in between the two different lives. I saw the advertisement of the lodgings in this farmhouse in an evening paper that somebody had left at the restaurant. That was when I was trying to make the change abruptly, and I may as well make a note of what happened.

After attending the funeral (which seemed to me an act of hypocrisy, as I hardly knew the man, but it was expected of me), I came back to my Charlotte Street rooms and had tea. I slept well that night. Then next morning I went to the office at the usual hour, in my best clothes, and with a deep band still on my hat. I went to Mr. Toller’s room and knocked. He said, ‘Come in,’ and after I had entered: ‘Can I do anything for you? What do you want?’

Then I explained to him that I wished to leave at once. He said:

‘This seems sudden, after thirty years’ service.’

‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘I have served you faithfully for thirty years, but things have changed, and I have now three hundred a year of my own. I will pay something in lieu of notice, if you like, but I cannot go on being a clerk any more. I hope, Mr. Toller, you will not think that I speak with any impertinence to yourself, or any immodesty, but I am really in the position of a private gentleman.’

He looked at me curiously, and as he did not say anything I repeated:

‘I think I am in the position of a private gentleman.’

In the end he let me go, and said very politely he was sorry to lose me. I said good-bye to the other clerks, even to those who had sometimes laughed at what they imagined to be my peculiarities. I gave the better of the two office-boys a small present in money.

I went back to the Charlotte Street rooms, but there was nothing to do there. There were figures going on in my head, and my fingers seemed to be running up and down columns. I had a stupid idea that I should be in trouble if Mr. Toller were to come in and catch me like that. I went out and had a capital lunch, and then I went to the theatre. I took a stall right in the front row, and sat there all by myself. Then I had a cab to the restaurant. It was too soon for dinner, so I ordered a whisky-and-soda, and smoked a few cigarettes. The man at the table next me left the evening paper in which I saw the advertisement of these farmhouse lodgings. I read the whole of the paper, but I have forgotten it all except that advertisement, and I could say it by heart now—all about bracing air and perfect quiet and the rest of it. For dinner I had a bottle of champagne. The waiter handed me a list, and asked which I would prefer. I waved the list away and said:

‘Give me the best.’

He smiled. He kept on smiling all through dinner until the end; then he looked serious. He kept getting more serious. Then he brought two other men to look at me. They spoke to me, but I did not want to talk. I think I fell asleep. I found myself in my rooms in Charlotte Street next morning, and my landlady gave me notice because, she said, I had come home beastly drunk. Then that advertisement flashed into my mind about the bracing air. I said:

‘I should have given you notice in any case; this is not a suitable place for a gentleman.’

June 3rd.—I am rather sorry that I wrote down the above. It seems so degrading. However, it was merely an act of ignorance and carelessness on my part, and, besides, I am writing solely for myself. To myself I may own freely that I made a mistake, that I was not used to the wine, and that I had not fully gauged what the effects would be. The incident is disgusting, but I simply put it behind me, and think no more about it. I pay here two pounds ten shillings a week for my two rooms and board. I take my meals, of course, by myself in the sitting-room. It would be rather cheaper if I took them with the family, but I do not care about that. After all, what is two pounds ten shillings a week? Roughly speaking, a hundred and thirty pounds a year.

June 17th.—I have made no entry in my diary for some days. For a certain period I have had no heart for that or for anything else. I had told the people here that I was a private gentleman (which is strictly true), and that I was engaged in literary pursuits. By the latter I meant to imply no more than that I am fond of reading, and that it is my intention to jot down from time to time my sensations and experiences in the new life which has burst upon me. At the same time I have been greatly depressed. Why, I can hardly explain. I have been furious with myself. Sitting in my own sitting-room, with a gold-tipped cigarette between my fingers, I have been possessed (even though I recognised it as an absurdity) by a feeling that if Mr. Toller were to come in suddenly I should get up and apologize. But the thing which depressed me most was the open country. I have read, of course, those penny stories about the poor little ragged boys who never see the green leaf in their lives, and I always thought them exaggerated. So they are exaggerated: there are the Embankment Gardens with the Press Band playing; there are parks; there are Sunday-school treats. All these little ragged boys see the green leaf, and to say they do not is an exaggeration—I am afraid a wilful exaggeration. But to see the open country is quite a different thing. Yesterday was a fine day, and I was out all day in a place called Wensley Dale. On one spot where I stood I could see for miles all round. There was not a single house, or tree, or human being in sight. There was just myself on the top of a moor; the bigness of it gave me a regular scare. I suppose I had got used to walls: I had got used to feeling that if I went straight ahead without stopping I should knock against something. That somehow made me feel safe. Out on that great moor—just as if I were the last man left alive in the world—I do not feel safe. I find the track and get home again, and I tremble like a half-drowned kitten until I see a wall again, or somebody with a surly face who does not answer civilly when I speak to him. All these feelings will wear off, no doubt, and I shall be able to enter upon the new phase of my existence without any discomfort. But I was quite right to take a few months’ quiet retirement. One must get used to things gradually. It was the same with the champagne—to which, by the way, I had not meant to allude any further.

June 20th.—It is remarkable what a fascination these very large moors have for me. It is not exactly fear any more—indeed, it must be the reverse. I do not care to be anywhere else. Instead of making this a mere pause between two different existences, I shall continue it. To that I have quite made up my mind. When I am out there in a place where I cannot see any trees, or houses, or living things, I am the last person left alive in the world. I am a kind of a god. There is nobody to think anything at all about me, and it does not matter if my clothes are not right, or if I drop an ‘h’—which I rarely do except when speaking very quickly. I never knew what real independence was before. There have been too many houses around, and too many people looking on. It seems to me now such a common and despicable thing to live among people, and to have one’s character and one’s ways altered by what they are going to think. I know now that when I ordered that bottle of champagne I did it far more to please the waiter and to make him think well of me than to please myself. I pity the kind of creature that I was then, but I had not known the open country at that time. It is a grand education. If Toller were to come in now I should say, ‘Go away. Go back to your bricks and mortar, and account-books, and swell friends, and white waistcoats, and rubbish of that kind. You cannot possibly understand me, and your presence irritates me. If you do not go at once I will have the dog let loose upon you.’ By the way, that was a curious thing which happened the other day. I feed the dog, a mastiff, regularly, and it goes out with me. We had walked some way, and had reached that spot where a man becomes the last man alive in the world. Suddenly the dog began to howl, and ran off home with its tail between its legs, as if it were frightened of something. What was it that the dog had seen and I had not seen? A ghost? In broad daylight? Well, if the dead come back they might walk here without contamination. A few sheep, a sweep of heather, a gray sky, but nothing that a living man planted or built. They could be alone here. If it were not that it would seem a kind of blasphemy, I would buy a piece of land in the very middle of the loneliest moor and build myself a cottage there.

June 23rd.—I received a letter to-day from Julia. Of course she does not understand the change which has taken place in me. She writes as she always used to write, and I find it very hard to remember and realize that I liked it once, and was glad when I got a letter from her. That was before I got into the habit of going into empty places alone. The old clerking, account-book life has become too small to care about. The swell life of the private gentleman, to which I looked forward, is also not worth considering. As for Julia, I was to have married her; I used to kiss her. She wrote to say that she thought a great deal of me; she still writes. I don’t want her. I don’t want anything. I have become the last man alive in the world. I shall leave this farmhouse very soon. The people are all right, but they are people, and therefore insufferable. I can no longer live or breathe in a place where I see people, or trees which people have planted, or houses which people have built. It is an ugly word—people.

July 7th.—I was wrong in saying that I was the last man alive in the world. I believe I am dead. I know now why the mastiff howled and ran away. The whole moor is full of them; one sees them after a time when one has got used to the open country—or perhaps it is because one is dead. Now I see them by moonlight and sunlight, and I am not frightened at all. I think I must be dead, because there seems to be a line ruled straight through my life, and the things which happened on the further side of the line are not real. I look over this diary, and see some references to a Mr. Toller, and to some champagne, and coming into money. I cannot for the life of me think what it is all about. I suppose the incidents described really happened, unless I was mad when I wrote about them. I suppose that I am not dead, since I can write in a book, and eat food, and walk, and sleep and wake again. But since I see them now—these people that fill up the lonely places—I must be quite different to ordinary human beings. If I am not dead, then what am I? To-day I came across an old letter signed ‘Julia Jarvis’; the envelope was addressed to me. I wonder who on earth she was?

July 9th.—A man in a frock-coat came to see me, and talked about my best interest. He wanted me, so far as I could gather, to come away with him somewhere. He said I was all right, or, at any rate, would become all right, with a little care. He would not go away until I said that I would kill him. Then the woman at the farmhouse came up with a white face, and I said I would kill her too. I positively cannot endure people. I am something apart, something different. I am not alive, and I am not dead. I cannot imagine what I am.

July 16th.—I have settled the whole thing to my complete satisfaction. I can without doubt believe the evidence of my own senses. I have seen, and I have heard. I know now that I am a god. I had almost thought before that this might be. What was the matter was that I was too diffident: I had no self-confidence; I had never heard before of any man, even a clerk in an old-established firm, who had become a god. I therefore supposed it was impossible until it was distinctly proved to be.

I had often made up my mind to go to that range of hills that lies to the north. They are purple when one sees them far off. At nearer view they are gray, then they become green, then one sees a silver network over the green. The silver network is made by streams descending in the sunlight. I climbed the hill slowly; the air was still, and the heat was terrible. Even the water which I drank from the running stream seemed flat and warm. As I climbed, the storm broke. I took but little notice of it, for the dead that I had met below on the moor had told me that lightning could not touch me. At the top of the hill I turned, and saw the storm raging beneath my feet. It is the greatest of mercies that I went there, for that is where the other gods gather, at such times as the lightning plays between them and the earth, and the black thunder-clouds, hanging low, shut them out from the sight of men.

Some of the gods were rather like the big pictures that I have seen on the hoardings, advertising plays at the theatre, or some food which is supposed to give great strength and muscular development. They were handsome in face, and without any expression. They never seemed to be angry or pleased, or hurt. They sat there in great long rows, resting, with the storm raging in between them and the earth. One of them was a woman. I spoke to her, and she told me that she was older than this earth; yet she had the face of a young girl, and her eyes were like eyes that I have seen before somewhere. I cannot think where I saw the eyes like those of the goddess, but perhaps it was in that part of my life which is forgotten and ruled off with a line. It gave one the greatest and most majestic feelings to stand there with the gods, and to know that one was a god one’s self, and that lightning did not hurt one, and that one would live for ever.

July 18th.—This afternoon the storm returned, and I hurried to the meeting-place, but it is far away to the hills, and though I climbed as quickly as I could the storm was almost passed, and they had gone.

August 1st.—I was told in my sleep that to-morrow I was to go back to the hill again, and that once more the gods would be there, and that the storm would gather round us, and would shut us from profane sight, and the steely lightnings would blind any eye that tried to look upon us. For this reason I have refused now to eat or drink anything; I am a god and have no need of such things. It is strange that now when I see all real things so clearly and easily—the ghosts of the dead that walk across the moors in the sunlight and the concourse of the gods on the hill-top above the storm—men and women with whom I once moved before I became a god are no more to me than so many black shadows. I scarcely know one from the other, only that the presence of a black shadow anywhere near me makes me angry, and I desire to kill it. That will pass away; it is probably some faint relic of the thing that I once was in the other side of my life on the other side of the line which has been ruled across it. Seeing that I am a god it is not natural that I can feel anger or joy any more. Already all feeling of joy has gone from me, for to-morrow, so I was told in my sleep, I am to be betrothed to the beautiful goddess that is older than the world, and yet looks like a young girl, and she is to give me a sprig of heather as a token and——

It was on the evening of August 1 he was found.