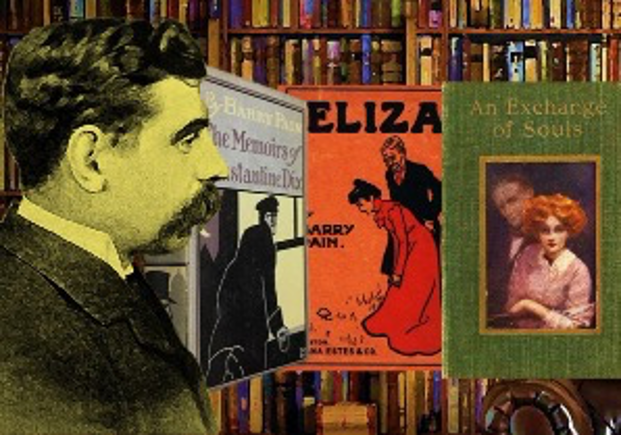

THE END OF A SHOW

by Barry Pain

It was a little village in the extreme north of Yorkshire, three miles from a railway-station on a small branch line. It was not a progressive village; it just kept still and respected itself. The hills lay all round it, and seemed to shut it out from the rest of the world. Yet folks were born, and lived, and died, much as in the more important centres; and there were intervals which required to be filled with amusement. Entertainments were given by amateurs from time to time in the schoolroom; sometimes hand-bell ringers or a conjurer would visit the place, but their reception was not always encouraging. “Conjurers is nowt, an ringers is nowt,” said the sad native judiciously; “ar dornt regard ’em.” But the native brightened up when in the summer months a few caravans found their way to a piece of waste land adjoining the churchyard. They formed the village fair, and for two days they were a popular resort. But it was understood that the fair had not the glories of old days; it had dwindled. Most things in connection with this village dwindled.

The first day of the fair was drawing to a close. It was half-past ten at night, and at eleven the fair would close until the following morning. This last half-hour was fruitful in business. The steam roundabout was crowded, the proprietor of the peep-show was taking pennies very fast, although not so fast as the proprietor of another, somewhat repulsive, show. A fair number patronized a canvas booth which bore the following inscription: POPULAR SCIENCE LECTURES, Admission Free.

At one end of this tent was a table covered with red baize; on it were bottles and boxes, a human skull, a retort, a large book, and some bundles of dried herbs. Behind it was the lecturer, an old man, gray and thin, wearing a bright, coloured dressing-gown. He lectured volubly and enthusiastically; his energy and the atmosphere of the tent made him very hot, and occasionally he mopped his forehead.

“I am about to exhibit to you,” he said, speaking clearly and correctly, “a secret known to few, and believed to have come originally from those wise men of the East referred to in Holy Writ.”

Here he filled two test-tubes with water, and placed some bluish-green crystals in one and some yellow crystals in the other. He went on talking, quoting scraps of Latin, telling stories, making local and personal allusions, finally coming back again to his two test-tubes, both of which now contained almost colourless solutions. He poured them both together into a flat glass vessel, and the mixture at once turned to a deep brownish purple. He threw a fragment of something on to the surface of the mixture, and that fragment at once caught fire. This favourite trick succeeded; the audience were undoubtedly impressed, and before they quite realized by what logical connection the old man had arrived at the subject, he was talking to them about the abdomen. He seemed to know the most unspeakable and intimate things about the abdomen. He had made pills which suited its peculiar needs, which he could, and would sell in boxes at sixpence and one shilling, according to size. He sold four boxes at once, and was back in his classical and anecdotal stage, when a woman pressed forward. She was a very poor woman. Could she have a box of these pills at half-price? Her son was very bad, very bad. It would be a kindness.

He interrupted her in a dry, distinct voice:

“Woman, I never yet did anyone a kindness, not even myself.”

However, a friend pushed some money into her hand, and she bought two boxes. It was past twelve o’clock now. The flaring lights were out in the little group of caravans on the waste ground. The tired proprietors of the shows were asleep. The gravestones in the churchyard were glimmering white in the bright moonlight. But at the entrance to that little canvas booth the quack doctor sat on one of his boxes, smoking a clay pipe. He had taken off the dressing-gown, and was in his shirt-sleeves; his clothes were black, much worn. His attention was arrested–he thought that he heard the sound of sobbing.

“It’s a God-forsaken world,” he said aloud. After a second’s silence he spoke again. “No, I never did a kindness even to myself, though I thought I did, or I I shouldn’t have come to this.”

He took his pipe from his mouth and spat. Once more he heard that strange wailing sound; this time he arose, and walked in the direction of it.

Yes, that was it. It came from that caravan standing alone where the trees made a dark spot.

The caravan was gaudily painted, and there were steps from the door to the ground. He remembered having noticed it once during the day. It was evident that someone inside was in trouble–great trouble. The old man knocked gently at the door.

“Who’s there? What’s the matter?”

“Nothing,” said a broken voice from within.

“Are you a woman?”

There was a fearful laugh.

“Neither man nor woman–a show.”

“What do you mean?”

“Go round to the side, and you’ll see.”

The old man went round, and by the light of two wax matches caught a glimpse of part of the rough painting on the side of the caravan. The matches dropped from his hand. He came back, and sat down on the steps of the caravan.

“You are not like that,” he said.

“No, worse. I’m not dressed in pretty clothes, and lying on a crimson velvet couch. I’m half naked, in a corner of this cursed box, and crying because my owner beat me. Now go, or I’ll open the door and show myself to you as I am now. It would frighten you; it would haunt your sleep.”

“Nothing frightens me. I was a fool once, but I have never been frightened. What right has this owner over you?”

“He is my father,” the voice screamed loudly; then there was more weeping; then it spoke again: “It’s awful; I could bear anything now–anything–if I thought it would ever be any better; but it won’t. My mind’s a woman’s and my wants are a woman’s, but I am not a woman. I am a show. The brutes stand round me, talk to me, touch me!”

“There’s a way out,” said the old man quietly, after a pause. An idea occurred to him.

“I know–and I daren’t take it–I’ve got a thing here, but I daren’t use it.”

“You could drink something–something that wouldn’t hurt?”

“Yes.”

“You are quite alone?”

“Yes; my owner is in the village, at the inn.”

“Then wait a minute.”

The old man hastened back to the canvas booth, and fumbled about with his chemicals. He murmured something about doing someone a kindness at last. Then he returned to the caravan with a glass of colourless liquid in his hand.

“Open the door and take it,” he said.

The door was opened a very little way. A thin hand was thrust out and took the glass eagerly.

The door closed, and the voice spoke again.

“It will be easy?”

“Yes.”

“Good-bye, then. To your health–”

The old man heard the glass crash on the wooden floor, then he went back to his scat in front of the booth, and carefully lit another pipe.

“I will not go,” he said aloud. “I fear nothing–not even the results of my best action.”

He listened attentively.

No sound whatever came from the caravan. All was still. Far away the sky was growing lighter with the dawn of a fine summer day.