GUSTAVO ADOLFO BECQUER

A Provençal Ballad.

“I was the true Teobaldo de Montagut, Baron of Fortcastell. Lord or serf, noble or commoner, thou, whosoever thou mayst be, who pausest an instant beside my sepulchre, believe in God, as I have believed, and pray for me.”

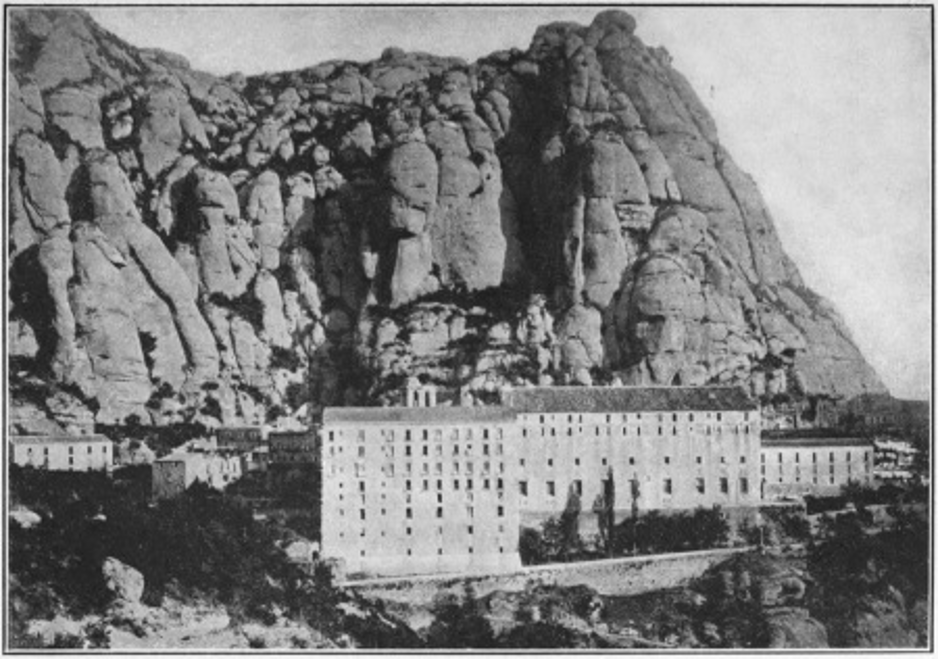

Ye gallant Knights Errant, who, lance in rest, vizor closed, mounted on powerful charger, ride the world over with no more patrimony than your illustrious name and your good sword, seeking honor and glory in the profession of arms,—if on crossing the rugged valley of Montagut you have been overtaken by night and storm and have found a refuge in the ruins of the monastery still to be seen in its bosom, hearken to me!

Ye Shepherds, who follow with slow step your herds that go grazing far and wide over the hills and plains, if on leading them to the border of the transparent rivulet which runs, struggling and leaping, amid the great rocks of the valley of Montagut in the drought of summer, ye have found, on a fiery afternoon, shade and slumber beneath the broken monastery arches, whose mossy pillars kiss the waves, hearken to me!

Little Daughters of the hamlets roundabout, ye wild lilies who bloom happy in the shelter of your humbleness, if on the morning of the Patron Saint of this locality, coming down into the valley of Montagut to gather clovers and daisies to deck his shrine, conquering the fear which the sombre monastery, rising on its rocks, strikes to your childish hearts, ye have ventured into its silent and deserted cloister to wander amid its forsaken tombs, on whose edges grow the fullest-petaled daisies and the bluest harebells, hearken to me!

Thou, Noble Knight, perchance by the gleam of a lightning flash; thou, Wandering Shepherd, bronzed by the fierce heat of the sun; thou, Lovely Child, still besprent with drops of dew like tears, all ye would have seen in that holy place a tomb, a lowly tomb. Formerly it consisted of an unhewn stone and a wooden cross; the cross has disappeared and only the stone remains. In this tomb, whose inscription is the motto of my song, rests in peace the last baron of Fortcastell, Teobaldo de Montagut, whose strange history I am about to tell.

I.

While the noble Countess of Montagut was pregnant with her firstborn son, Teobaldo, she had a strange and terrible dream. Perchance a divine warning; mayhap a vain fantasy which time made real in later years. She dreamed that in her womb she had borne a serpent, a monstrous serpent that, darting out shrill hisses, now gliding through the short grass, now coiling upon itself for a spring, fled from her sight, hiding at last in a clump of briers.

“There it is! there it is!” shrieked the Countess in her horrible nightmare, pointing out to her servitors the brambles among which the nauseous reptile had sought concealment.

When the servitors had swiftly reached the spot which the noble lady, motionless and overwhelmed by a profound terror, was still pointing out to them with her finger, a white dove rose from out the prickly thicket and soared to the clouds.

The serpent had disappeared.

II.

Teobaldo was born. His mother died in giving him birth; his father perished a few years later in an ambuscade, warring like a good Christian against the Moors, the enemies of God.

From this time on the youth of the heir of Fortcastell can be likened only to a hurricane. Wherever he went, his way was marked by a trail of tears and blood. He hanged his vassals, he fought his equals, he pursued maidens, he beat the monks, and never ceased from oaths and blasphemies. There was no saint in peace, no hallowed thing, he did not curse.

III.

One day when he was out hunting and when, as was his custom, he had had all his devilish retinue of profligate pages, inhuman archers and debased servants, with the dogs, horses and gerfalcons, take shelter from the rain in a village church of his demesne, a venerable priest, daring the young lord’s wrath, not quailing at thought of the fury-fits of that wild nature, raised the consecrated Host in his hands and conjured the invader in the name of Heaven to depart from that place and go on foot, with pilgrim staff, to entreat of the Pope absolution for his crimes.

“Leave me alone, old fool!” exclaimed Teobaldo on hearing this,—“leave me alone! Or, since I have not come on a single quarry all day long, I will let loose my hounds and chase thee like a wild boar for my sport.”

IV.

With Teobaldo a word was a deed. Yet the priest made no answer save this:

“Do what thou wilt, but remember that there is a God who chastises and who pardons. If I die at thy hands, He will blot out my sins from the book of His displeasure, to write thy name in their place and to make thee expiate thy crime.”

“A God who chastises and pardons!” interrupted the blasphemous baron with a burst of laughter. “I do not believe in God and, by way of proof, I am going to carry out my threat; for though not much given to prayer, I am a man of my word. Raimundo! Gerardo! Pedro! Set on the pack! give me a javelin! blow the alali on your horns, since we will hunt down this idiot, though he climb to the tops of his altars.”

V.

After an instant’s hesitation and a fresh command from their lord, the pages began to unleash the greyhounds that filled the church with the din of their eager barking; the baron had strung his crossbow, laughing a Satanic laugh; and the venerable priest, murmuring a prayer, was, with his eyes raised to heaven, tranquilly awaiting death, when there rose outside the sacred enclosure a wild halloo, the braying of horns proclaiming that the game had been sighted, and shouts of After the boar! Across the brushwood! To the mountain! Teobaldo, at this announcement of the longed-for quarry, dashed open the doors of the church, transported by delight; behind him went his retainers, and with his retainers the horses and hounds.

VI.

“Which way went the boar?” asked the baron as he sprang upon his steed without touching the stirrups or unstringing his bow. “By the glen which runs to the foot of those hills,” they answered him. Without hearing the last word, the impetuous hunter buried his golden spur in the flank of the horse, who bounded away at full gallop. Behind him departed all the rest.

The dwellers in the hamlet, who had been the first to give the alarm and who, at the approach of the terrible beast, had taken refuge in their huts, timidly thrust out their heads from behind their window-shutters, and when they saw that the infernal troop had disappeared among the foliage of the woods, they crossed themselves in silence.

VII.

Teobaldo rode in advance of all. His steed, swifter by nature or more severely goaded than those of the retainers, followed so close to the quarry that twice or thrice the baron, dropping his bridle upon the neck of the fiery courser, had stood up in his stirrups and drawn the bow to his shoulder to wound his prey. But the boar, whom he saw only at intervals among the tangled thickets, would again vanish from view to reappear just out of reach of the arrow.

So he pursued the chase hour after hour, traversing the ravines of the valley and the stony bed of the stream, until, plunging into a deep forest, he lost his way in its shadowy defiles, his eyes ever fixed on the coveted game he constantly expected to overtake, only to find himself constantly mocked by its marvellous agility.

VIII.

At last, he had his chance; he extended his arm and let fly the shaft, which plunged, quivering, into the loin of the terrible beast that gave a leap and a frightful snort.—“Dead!” exclaims the hunter with a shout of glee, driving his spur for the hundredth time into the bloody flank of his horse. “Dead! in vain he flees. The trail of his flowing blood marks his way.” And so speaking, Teobaldo commenced to sound upon his bugle the signal of triumph that his retinue might hear.

At that instant his steed stopped short, its legs gave way, a slight tremor shook its strained muscles, it fell flat to the ground, shooting out from its swollen nostrils, bathed in foam, a rill of blood.

It had died of exhaustion, died when the pace of the wounded boar was beginning to slacken, when but one more effort was needed to run the quarry down.

IX.

To paint the wrath of the fierce-tempered Teobaldo would be impossible. To repeat his oaths and his curses, merely to repeat them, would be scandalous and impious. He shouted at the top of his voice to his retainers, but only echo answered him in those vast solitudes, and he tore his hair and plucked at his beard, a prey to the most furious despair.—“I will run it down, even though I break every blood-vessel in my body,” he exclaimed at last, stringing his bow anew and making ready to pursue the game on foot; but at that very instant he heard a sound behind him; the thick branches of the wood opened, and before his eyes appeared a page leading by the halter a charger black as night.

“Heaven hath sent it to me,” exclaimed the hunter, leaping upon its loins lightly as a deer. The page, who was thin, very thin, and yellow as death, smiled a strange smile as he handed him the bridle.

X.

The horse whinnied with a force which made the forest tremble, gave an incredible bound, a bound that raised him more than thirty feet above the earth, and the air began to hum about the ears of the rider, as a stone hums, hurled from a sling. He had started off at full gallop; but at a gallop so headlong that, afraid of losing the stirrups and in his dizziness falling to the ground, he had to shut his eyes and with both hands clutch the streaming mane.

And still without a shake of the reins, without touch of spur or call of voice, the steed ran, ran without ceasing. How long did Teobaldo gallop thus, unwitting where, feeling the branches buffet his face as he rushed by, and the brambles tear at his clothing, and the wind whistle about his head? No human being knows.

XI.

When, recovering courage, he opened his eyes an instant to throw a troubled glance about him, he found himself far, very far from Montagut, and in a district that was to him entirely unknown. The steed ran, ran without ceasing, and trees, rocks, castles and villages passed by him like a breath. New and still new horizons opened to his view,—horizons that melted away only to give place to others stranger and yet more strange. Narrow valleys, bristling with colossal fragments of granite which the tempests had torn down from mountain-summits; smiling plains, covered with a carpet of verdure and sprinkled over with white villages; limitless deserts, where the sands seethed beneath the searching rays of a sun of fire; immeasurable wildernesses, boundless steppes, regions of eternal snow, where the gigantic icebergs, standing out against a dim grey sky, were like white phantoms reaching out their arms to seize him by the hair as he fled past; all this, and thousands of other sights that I cannot depict, he saw in his wild race, until, enveloped in an obscure cloud, he ceased to hear the tramp of his horse’s hoofs beating the ground.

I.

Noble Knights, Shepherds, Lovely Little Maids who hearken to my lay, if what I tell be a marvel in your ears, deem it not a fable woven at my whim to steal a march on your credulity; from mouth to mouth this tradition has been passed down to me, and the inscription upon the tomb which still abides in the monastery of Montagut is an unimpeachable proof of the veracity of my words.

Believe, then, what I have told, and believe what I have yet to tell, for it is as certain as the foregoing, although more wonderful. Perchance I shall be able to adorn with a few graces of poetry the bare skeleton of this simple and terrible history, but never will I consciously depart one iota from the truth.

II.

When Teobaldo ceased to perceive the hoof-beats of his courser and felt himself hurled forth upon the void, he could not repress an involuntary shudder of terror. Up to this point he had believed that the objects which flashed before his eyes were the wild visions of his imagination, perturbed as it was by giddiness, and that his steed ran uncontrolled, to be sure, but still ran within the boundaries of his own seigniory. Now there remained no doubt that he was the sport of a supernatural power, which was hurrying him he knew not whither, through those masses of dark clouds, clouds of freakish and fantastic forms, in whose depths, lit up from time to time by flashes of lightning, he thought he could distinguish the burning thunderbolts about to break upon him.

The steed still ran, or, be it better said, swam now in that ocean of vague and fiery vapors, and the wonders of the sky began to display themselves one after another before the astounded eyes of his rider.

III.

He saw the angels, ministers of the wrath of God, clad in long tunics with fringes of fire, their burning hair loose on the hurricane, their brandished swords, which flashed the lightning, throwing out sparks of crimson light,—he saw this heavenly cavalry wheeling upon the clouds, sweeping like a mighty army over the wings of the tempest.

And he mounted higher, and he deemed he descried, from far above, the stormy clouds like a sea of lava, and heard the thunder moan below him as moans the ocean breaking on the cliff from whose summit the pilgrim views it all amazed.

IV.

And he saw the archangel, white as snow, who, throned on a great crystal globe, steers it through space in the cloudless nights like a silver boat over the surface of an azure lake. And he saw the sun revolving in splendor on golden axles through an atmosphere of color and of flame, and at its centre the fiery spirits who dwell unharmed in that intensest glow and from its blazing heart entone to their Creator hymns of praise.

He saw the threads of imperceptible light which bind men to the stars, and he saw the rainbow arch, thrown like a colossal bridge across the abyss which divides the first from the second heaven.

V.

By a mystic stair he saw souls descend to earth; he saw many come down, and few go up. Each one of these innocent spirits went accompanied by a most radiant archangel who covered it with the shadow of his wings. The archangels who returned alone came in silence, weeping; but the others mounted singing like the larks on April mornings.

Then the rosy and azure mists which floated in the ether, like curtains of transparent gauze, were rent, as Holy Saturday, the Day of Glory, rends in our churches the veiling of the altars, and the Paradise of the Righteous opened, dazzling in its beauty, to his gaze.

VI.

There were the holy prophets whom you have seen rudely sculptured on the stone portals of our cathedrals, there the shining virgins whom the painter vainly strives, in the stained glass of the ogive windows, to copy from his dreams; there the cherubim with their long and floating robes and haloes of gold; as in the altar pictures; there, at last, crowned with stars, clad in light, surrounded by all the celestial hierarchy, and beautiful beyond all thought, Our Lady of Montserrat, Mother of God, Queen of Archangels, the shelter of sinners and the consolation of the afflicted.

VII.

Beyond the Paradise of the Righteous; beyond the throne where sits the Virgin Mary. The mind of Teobaldo was stricken by terror; a fathomless fear possessed his soul. Eternal solitude, eternal silence live in those spaces that lead to the mysterious sanctuary of the Most High. From time to time a rush of wind, cold as the blade of a poniard, smote his forehead,—a wind that shriveled his hair with horror and penetrated to the marrow of his bones,—a wind like to those which announced to the prophets the approach of the Divine Spirit. At last he reached a point where he thought he perceived a dull murmur that might be likened to the far-off hum of a swarm of bees, when, in autumn evenings, they hover around the last of the flowers.

VIII.

He crossed that fantastic region whither go all the accents of the earth, the sounds which we say have ceased, the words which we deem are lost in the air, the laments which we believe are heard of none.

There, in a harmonious circle, float the prayers of little children, the orisons of virgins, the psalms of holy hermits, the petitions of the humble, the chaste words of the pure in heart, the resigned moans of those in pain, the sobs of souls that suffer and the hymns of souls that hope. Teobaldo heard among those voices, that throbbed still in the luminous ether, the voice of his sainted mother who prayed to God for him; but he heard no prayer of his own.

IX.

Further on, thousands on thousands of harsh, rough accents wounded his ears with a discordant roar,—blasphemies, cries for vengeance, drinking songs, indecencies, curses of despair, threats of the helpless, and sacrilegious oaths of the impious.

Teobaldo traversed the second circle with the rapidity of a meteor crossing the sky in a summer evening, that he might not hear his own voice which vibrated there thunderously loud, exceeding all other voices in the stress of that infernal concert.

“I do not believe in God! I do not believe in God!” still spake his tone beating through that ocean of blasphemies; and Teobaldo began to believe.

X.

He left those regions behind him and crossed other illimitable spaces full of terrible visions, which neither could he comprehend nor am I able to conceive, and finally he came to the uppermost circle of the spiral heavens, where the seraphim adore Jehovah, covering their faces with their triple wings and prostrate at His feet.

He would see God.

A waft of fire scorched his face, a sea of light darkened his eyes, unbearable thunder resounded in his ears and, caught from his charger and hurled into the void, like an incandescent stone shot out from a volcano, he felt himself falling, and falling without ever alighting, blind, burned and deafened, as the rebellious angel fell when God overthrew with a breath the pedestal of his pride.

I.

Night had shut in, and the wind moaned as it stirred the leaves of the trees, through whose luxuriant foliage was slipping a soft ray of moonlight, when Teobaldo, rising upon his elbow and rubbing his eyes as if awakening from profound slumber, looked about him and found himself in the same wood where he had wounded the boar, where his steed fell dead, where was given him that phantasmal courser which had rushed him away to unknown, mysterious realms.

A deathlike silence reigned about him, a silence broken only by the distant calling of the deer, the timid murmur of the leaves, and the echo of a far-off bell borne to his ears from time to time upon the gentle gusts.

“I must have dreamed,” said the baron, and set forth on his way across the wood, coming out at last into the open.

II.

At a great distance, and above the rocks of Montagut, he saw the black silhouette of his castle standing out against the blue, transparent background of the night sky—“My castle is far away and I am weary,” he muttered. “I will await the day in this village-hut near by,” and he bent his steps to the hut. He knocked at the door. “Who are you?” they demanded from within. “The Baron of Fortcastell,” he replied, and they laughed in his face. He knocked at another door. “Who are you and what do you want?” these, too, asked him. “Your liege lord,” urged the knight, surprised that they did not recognize him. “Teobaldo de Montagut.” “Teobaldo de Montagut!” angrily repeated the person within, a woman not yet old. “Teobaldo de Montagut, the count of the story! Bah! Go your way and don’t come back to rouse honest folk from their sleep to hear your stupid jests.”

III.

Teobaldo, full of astonishment, left the village and pursued his way to the castle, at whose gates he arrived when it was scarcely dawn. The moat was filled up with great blocks of stone from the ruined battlements; the raised drawbridge, now useless, was rotting as it still hung from its strong iron chains, covered with rust though they were by the wasting of the years; in the homage-tower slowly tolled a bell; in front of the principal arch of the fortress and upon a granite pedestal was raised a cross; upon the walls not a single soldier was to be discerned; and, indistinct and muffled, there seemed to come from its heart like a distant murmur a sacred hymn, grave, solemn and majestic.

“But this is my castle, beyond a doubt,” said Teobaldo, shifting his troubled gaze from one point to another, unable to comprehend the situation. “That is my escutcheon, still engraved above the keystone of the arch. This is the valley of Montagut. These are the lands it governs, the seigniory of Fortcastell”—

At this instant the heavy doors swung upon their hinges and a monk appeared beneath the lintel.

IV.

“Who are you and what are you doing here?” demanded Teobaldo of the monk.

“I am,” he answered, “a humble servant of God, a monk of the monastery of Montagut.”

“But”—interrupted the baron. “Montagut? Is it not a seigniory?”

“It was,” replied the monk, “a long time ago. Its last lord, the story goes, was carried off by the Devil, and as he left no heir to succeed him in the fief, the Sovereign Counts granted his estate to the monks of our order, who have been here for a matter of from one hundred to one hundred and twenty years. And you—who are you?”

“I”—stammered the Baron of Fortcastell, after a long moment of silence, “I am—a miserable sinner, who, repenting of his misdeeds, comes to make confession to your abbot and beg him for admittance into the bosom of his faith.”