CHAPTER I.

MINNIE AND HER PARROT.

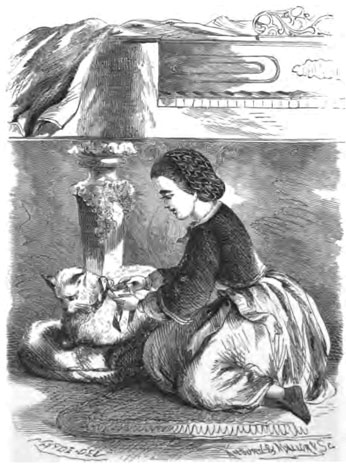

In these little books, I am going to tell you about Minnie, her home, and her pets; and I hope it will teach every boy and every girl who reads them to be kind to animals, as Minnie was. Minnie Lee had a pleasant home. She was an only child, and as her parents loved to please her, they procured every thing which they thought would make her happy. The first pet Minnie had was a beautiful tortoise-shell kitten, which she took in her baby arms and hugged tightly to her bosom. After a time, her father, seeing how much comfort she took with kitty, bought her a spaniel. He already had a large Newfoundland dog; but Mrs. Lee was unwilling to have him come into the house, saying that in summer he drew the flies, and in winter he dirtied her hearth rugs. So Leo, as the great dog was called, was condemned to the barn, while Tiney could rove through the parlors and chambers whenever he pleased.

In Minnie’s seventh year, her father bought her a Shetland pony and a lamb, which he told her was called a South Down —a rare and valuable breed. The little girl now thought her hands quite full; but only the next Christmas, when her uncle came home from sea, he told her he had brought an addition to her pets; and true enough, when his luggage came from town, there was a bag containing a real, live monkey, named Jacko.

These, with the silver-gray parrot, which had been in the family for years, gave Minnie employment from morning till night.

You will wonder, perhaps, that one child should have so many pets; and, indeed, the parrot belonged to her mother; but when I tell you that, though her parents had had six children, she was the only one remaining to them, and that in her infancy she was very sickly, you will not wonder so much. The doctor said that their only hope of bringing her up was to keep her in the open air as much as possible.

“Let her have a run with Leo,” he used to say; or, “Get her a horse, and teach her to ride. That will do her more good than medicine.”

When her father came home from town, if he did not see his little daughter on the lawn, playing with Fidelle, the cat, and Tiney, the dog, he was almost sure to find her in the shed where Jacko’s cage was kept, with Miss Poll perching on her shoulder.

When visitors called and asked to see her, her mother would laugh, as she answered, “I’m sure I don’t know where the child is, she has so many pets.”

Minnie was not allowed to study much in books; indeed, she scarcely knew how to read at all; yet she was not an ignorant child, for her father and mother took great pains to teach her. She knew the names of all the different trees on her father’s place, and of all the flowers in her mother’s garden; but her favorite study was the natural history of beasts and birds; and nothing gave her so much pleasure as to have her father relate anecdotes of their intelligence and sagacity.

He had a large, well-selected library, where were many rare volumes on her favorite subject, illustrated with pictures of different animals. When Mr. Lee could not recall a story as often as she wished, she would take his hand and coax him to the library. Then she would run up the steps to her favorite shelf, and taking down a book almost as large as she could lift, say, playfully, “Now, father, I’m ready for you to read.”

Mrs. Lee often found them sitting together, talking over the wonderful feats of some dog, cat, horse, or monkey, and laughed as she said to her husband, “I believe Minnie comes naturally by her love for animals, for you seem as much interested in the stories as she does.”

Mr. Lee lived in a very handsome house about seven miles from the city where he did business. He had made a great deal of money by sending ships to foreign lands, freighted with goods, which he sold there in exchange for others which were needed at home. He now lived quite at his ease, with plenty of servants to do his bidding, and horses and carriages to carry him wherever he wished to go.

But in this volume I shall speak of himself, his family, equipage, and estate, only as they are connected with my object, which is to tell you about Minnie’s pet parrot, and also to relate stories of other parrots, all of which are strictly true.

Poll was brought from the coast of Africa by a sea captain, who presented her to a lady, aunt to Mrs. Lee. At the lady’s death it was given to her niece, and had been an important member of the family ever since. It was not known how old she was when she was brought to America; but she had been in the family for fifteen years, and therefore was old enough to know how to behave herself properly on all occasions.

Miss Poll had a plumage of silver-gray feathers, with a brilliant scarlet tail. Her eyes were a bright yellow, with black pupils, and around them a circle of small white feathers. Her beak was large and strong, hooked at the end. Her tongue was thick and black. Her claws were also black, and she could use them as freely as Minnie used her hands. When her mistress offered her a cup of tea,—a drink of which she was very fond,—she took it in her claws, and drank it as gracefully as any lady.

In the morning, when her cage was cleaned, she always had a cup of canary seed; but at other times she ate potato, cracker, bread, apple, and sometimes a piece of raw meat. She liked, too, to pick a chicken bone, and would nibble away upon it, laughing and talking to herself in great glee.

Miss Poll, I am sorry to say, was very proud and fond of flattery. If Mrs. Lee went to the cage, and put out her finger for the bird to light upon it, and did not praise her, she would often bite it. But if she said, “Sweet Poll! dear Poll! she is a darling!” she would arch her beautiful neck, and look as proud as any proud miss. Then she would tip her head, and put her claws in her mouth, just like a bashful little girl.

Poll was exceedingly fond of music, and learned a tune by hearing it played a few times; but she had a queer habit of leaving off in the middle of a line, when she would whistle for the dog, or call out, “Leo, come here! lie down, you rascal!”

Poll was very fond of Minnie, and indeed of all children.

When she saw the little girl come into the room with her bonnet on, she exclaimed, in a natural tone, “Going out, hey?” When Minnie laughed, she would laugh too, and keep repeating, “Going out? Good by.”

Parrots are said to be very jealous birds, and are displeased to have any attention shown to other pets.

I think Poll was so, and that she was angry when she saw Minnie show so much kindness to Fidelle. One day she thought she would punish the kitty; so she called, “Kitty, kitty,” in the most sweet, coaxing tones. Puss seemed delighted, and walked innocently up to the cage, which happened to be set in a chair.

“Kitty, kitty,” repeated Poll, until she had the little creature within reach of her claws, when she suddenly caught her, and bit her ears and her tail, Fidelle crying piteously at this unexpected ill treatment, until some one came to rescue her. Then puss crept softly away to the farther end of the room, and hid under a chair, where she began to lick her wounded tail, while Poll laughed and chuckled over the joke.

CHAPTER II.

THE PARROT AND THE TRAVELLER.

One morning when the whole family were in the breakfast room, Poll began to talk to herself, imitating exactly the manner of a lady who had recently visited the house with her children.

“Little darling beauty, so she is; she shall have on her pretty new bonnet, and go ridy, ridy with mamma; so she shall.”

In the midst of this, the bird stopped and began to cry like an impatient child.

“Don’t cry, sweet,” she went on, changing her voice again; “there, there, pet, don’t cry; hush up, hush up.”

This conversation she carried on in the most approved baby style, until, becoming excited by the laughter of the company, she stopped, and began to laugh too.

After this, whenever she wanted to be very cunning, she would repeat this performance, much to the amusement of all who heard her.

Poll was a very mischievous bird, and on this account was not let out of her cage, unless Minnie or some one was at liberty to watch her.

Mrs. Lee, who usually sat in the back parlor, from which place she could hear Poll talk, was sure to know if the bird was doing any great mischief, for she always began to scold herself on such occasions.

“Ah, ah!” she exclaimed, one day; “what are you about, Poll?”

Mrs. Lee rose quickly, and advanced on tiptoe to the door, where she saw the parrot picking at some buttons on the sofa, which she had often been forbidden to touch. Much amused at the sight, she listened to an imitation of her own voice, as follows:—

“Go away, I tell you, Poll! I see you! Take care!”

Finding her buttons fast disappearing, she suddenly entered, when the bird went quickly back to her perch.

In the afternoon, when her husband returned from town, she related the incident to him and to Minnie.

“That shows us,” answered the gentleman, laughing, “how careful we ought to be what we say before her; we shall be sure to hear it again.”

After tea, when Minnie and her father were in the library, they heard Poll singing a variety of tunes in her merriest tones. They stopped talking a while to listen, and then both laughed heartily to see how quickly she struck into a whistle, as Tiney walked deliberately into the room in search of her little mistress.

“What a funny bird she is!” cried Minnie; “she runs on so from one thing to another.”

“In that respect she shows a want of judgment,” replied her father; “but, by the way, I have a story for you of a curious parrot, which I will read.

“A gentleman who had been visiting a friend near the sea shore, and concluded to return by way of a ferry boat, walked to the beach to see whether there was one ready to start. As he stood looking over the water, much disappointed that there was none in sight, he was surprised to hear the loud cry of the boatman,—

“‘Over, master? Going over?’

“‘Yes, I wish to go,’ he answered, looking eagerly about.

“‘Over, master? Going over?’ was asked again in a more earnest tone; and again he repeated,—

“‘Yes, I wish to go as soon as possible.’

“The questions were repeated constantly, and yet no preparation was made for granting his request. He began to be somewhat indignant, and seeing no one near upon whom he could vent his wrath, he walked rapidly toward a public house near by. Here his anger was speedily changed to mirth, for on going near the door he saw a parrot hanging in a cage over the porch, from whom all the noise had proceeded.”

“Oh, father,” exclaimed Minnie, greatly delighted, “that was a real good story. Isn’t there another one?”

“Yes; here is one where a man made his bird revenge his insults.

“There was once a distiller who had long suffered in his business by a neighbor, who had several times reported him to the public authorities as one who made and sold rum without a license to do so. At last he became very angry at being interfered with, and, as no ready means offered to revenge himself, he adopted the following singular method.

“He had a large green parrot, which could speak almost anything. This parrot he taught to repeat, in a clear, loud, and distinct voice, the ninth commandment,—‘Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.’

“Having committed this lesson satisfactorily, the owner of the parrot hung him outside one of the front windows of the house, where his troublesome neighbor, who lived directly opposite, would be able to have the full benefit of the inspired words.

“The first time the neighbor came in sight, the parrot began, ‘Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor;’ and this was repeated on every occasion, to the great delight of the neighborhood.”

At this moment, Mrs. Lee opened the door, to tell Minnie that Anne, the nurse, was waiting to put her to bed.

“It’s too early,” began the child, impatiently; “I don’t want to go yet.”

Her mother only answered by pointing to the little French timepiece on the mantel.

“I was having such a good time,” sobbed Minnie; “I always have to go just when I’m enjoying myself the most.”

Hearing this, Poll instantly began to whine, “I don’t want to go,” and then, putting her claw up to her mouth, sobbed, for all the world, just like her little mistress.

Minnie wanted to laugh, but she felt ashamed, and did not like to have her parents see her; so she said, “Keep still, Poll; you’ve nothing to do with it.”

This reproof only excited the bird the more, and in a loud, angry tone, she went on,—

“Keep, still, Poll! don’t meddle! don’t meddle! Ah, Poll,what are you about? Take care; I see you!”

Mr. Lee watched his daughter anxiously, to see whether she would recover her temper, and was pleased to observe that she presently advanced to the cage, when she held out her finger to say “Good night” to her pet, as usual.

“Good night; say your prayers,” repeated the bird, holding out her claw.

She then gave her parents their good-night kiss, and snatching Tiney in her arms, went gayly from the room.

CHAPTER III.

POLL’S FUNNY TRICKS.

In summer, Poll lived mostly out of doors, hung in a cage at the top of the piazza. Here she seemed very much amused at the various operations she witnessed.

In the morning, she was placed in front of the house on account of the shade; but after dinner, the cage was carried round to a porch, where the shed and barn were in full view.

From the front porch, she could salute all the early visitors, and watch the butcher’s cart as it passed, often startling him with the inquiry,—

“What have you to-day?” Then, if no one answered, she would quickly reply, “Veal,” or, “Only veal to-day.”

But her greatest amusement was to watch a family of children, who lived nearly opposite. There was one child just commencing to go to school—a duty which he disliked exceedingly.

As soon as Poll saw him she would begin, “You must go, or you’ll grow up a dunce.”

Then she would whine, and cry, “I won’t go, I say I won’t.”

“Go right along, you naughty boy, or I shall tell your father.”

Poll now begins to sob and sniffle in earnest, when she suddenly stops and begins the whole conversation over again, greatly to the merriment of her hearers.

There is, however, one trick that Poll has learned, which is quite inconvenient.

Near Mr. Lee’s house, the ground rises, his residence being on a hill. Teams loaded with coal, and other heavy articles, continually pass by, it being of course quite an object with the drivers to get the horses to the top of the hill without stopping on the way.

But this would spoil Miss Poll’s fun. When they are about half way up, and just in the steepest part, she calls out, “Whoa,” in a loud, authoritative voice, so exactly in imitation of the driver that they obey at once. This she repeats as often as he attempts to start them forward, until, greatly vexed, I am sorry to say, he sometimes swears at both the horses and the bird.

Nor is this all. When the teams have reached the top of the hill, and the driver wishes to let them stop and breathe, Poll begins to cluck for them to go on, and will not let them rest until they are out of her sight, when she begins a hearty laugh over her own joke. In the mean time, the driver frets and fumes, and wishes that bird had the driving of those horses for once.

Poll has formed quite an acquaintance with most of the children of the neighborhood. At one time, there was a great excitement among the boys in regard to a company of soldiers they were forming. On Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, they marched up and down the street, past Mr. Lee’s, beating a drum, and singing, “Rub-a-dub, dub! rub-a-dub, dub! Hurrah, hurrah!” As soon as they were out of hearing, Poll began the story, and went through the drill with great glee.

From the back porch, Poll witnessed the grooming of the horses, when, as was often the case, they were taken out for Mrs. Lee and Minnie to ride. Indeed, she did her best, as far as words could go, to assist in the operation. While the har ness was being put on, she continually called out, “Back, sir! Stand still! What are you about there?” This was often done, greatly to the discomfiture of the hostler, who was obliged generally to countermand these orders.

I have told you that Poll was very fond of her friends, and jealous of their affection. She was also very strong in her dislikes. There was one member of the family whom she could not endure, and she took every occasion to vent her spite against him. This was the colored boy who blacked the boots, scoured the knives, and ran errands.

Early one morning, when Poll was hanging up at a back window, she saw Tom polishing the boots, and whistling a merry tune, never once thinking of his enemy near him. Squeezing herself, as she often did, through the wires of her cage, she crept silently along through an inner room into the shed, when she flew directly at him, caught him by the legs, and held him fast.

Poor Tom was frightened nearly out of his senses, and yelled for some one to take the parrot away. The servants enjoyed the fun too well, however, to release him. They laughed heartily, telling him to shake her off; but he was paralyzed with fright, and stood the picture of horror until the cook coaxed Poll away.

At another time, she took a great dislike to the groom, who was an Irishman. Watching a favorable opportunity, she flew at him, caught hold of his shirt bosom, and held it so tightly with her strong beak, that it was some time before Mrs. Lee, who was attracted to the kitchen by the noise, could make her let go her hold of the astonished object of her hatred.

After this, whenever the women servants were displeased with the man, they would slyly let Poll out of her cage, when she darted directly toward him, and was thus the means of his losing many a dinner.

When his grievances became too heavy, he complained to his mistress, who soon put a stop to such unjust proceedings.

One evening, when Mr. Lee drove into the yard, he heard Minnie laughing heartily. Approaching nearer, he saw her sitting on the piazza; Leo, looking rather ashamed, crouching at her feet; and Poll talking, in great excitement, in exact imitation of his own tones—

“Leo, come here! good fellow! Down, sir! Leo, Leo! Hurrah, boys; what fun!”

As it was near the time for his master’s return, the dog had been more readily deceived by the parrot’s call, and had run rapidly toward the house, when he perceived that he had been made a fool of, as he often had been before.

A few hours later, they were talking it over in the library, when Mr. Lee said he thought he had read an incident very similar.

Minnie joyfully clapped her hands, while her father took down the book, and read,—

“A parrot belonging to a gentleman in Boston was once sunning himself in his cage, at the door of a shop. Seeing a dog in the distance, he began to whistle, when the animal, imagining it to be the call of his master, ran swiftly toward the house.

“At this moment, the bird exclaimed, ‘Get out, you brute! ’ when the astonished dog hastily retreated, leaving the parrot laughing and enjoying the joke.”

“That reminds me,” added Mrs. Lee, “of a story a lady once told me of a parrot she owned, and which was really a wonderfully intelligent bird. A new family moved into the neighborhood, consisting, among others, of two young ladies, who always dressed very gayly.

“Polly had a bad habit of making remarks upon the passers by, as she hung in her cage overlooking the main street. If, as was sometimes the case, persons engaged in conversation stopped near the house, they would often be startled by the cry,—

“‘Go home, now! Want to quarrel?’

“But when she saw ladies dressed fashionably, she gave utterance to a most contemptuous laugh, which would have been insult enough by itself; but she often accompanied it by the words,—

“‘La, how smart I do feel!’

“My friend called at once on her new neighbors, but unfortunately found they were out; she waited a long time for the call to be returned, and at last began to wonder that no notice was taken of her politeness, when the cause of the neglect was explained by a mutual friend.

“It appeared that on several occasions the young ladies had passed the house, and had heard the insulting laugh and words, which they attributed to my friend; so that when asked whether they had become acquainted with Mrs. G., they answered, coolly, ‘We have no wish to make her acquaintance.’

“Being pressed for a reason, they at last confessed that they had been repeatedly insulted, and narrated in what manner it had happened.

“This answer caused such a burst of merriment that they were surprised, until, being told that it was the chattering of a tame parrot, they soon joined in the laugh, and went at once to make her acquaintance, and also that of her mistress.”

CHAPTER IV.

POLL AT THE PARTY.

“Please, mamma, tell me all you can remember about Mrs. G.’s parrot,” cried Minnie, a few days later. “Was she as wonderful as our Poll? and was she as handsome?”

Mrs. Lee smiled. “If I should answer all your questions,” she said presently, “I should have work for the rest of the day.My friend’s parrot was green, with a brilliant red neck and tail. She was a great talker, and seemed to understand the meaning of much of what was said in her presence. I can recollect now two or three incidents which are well worth repeating.

“Polly was very fond of children, and enjoyed being let out of her cage to play with them as much as our Poll does. One day, when Mrs. G. had company, they were all startled by hearing loud and repeated screams of distress. Recognizing the voice of her favorite bird, my friend ran hastily into the yard, expecting to see Polly in some dreadful trouble. To her surprise, there was the bird perched safely on the clothes line; but going a few steps farther, she saw her youngest child, a darling girl between two and three years old, just balancing over the edge of a hogshead of water, and entirely unable to recover herself, or to utter one sound. Situated as she was, the poor child could not have remained long in that position, and, but for the alarm given by the watchful bird, must have fallen into the water and drowned.”

“O, wasn’t that a good bird, mamma? I’m sure they all must have loved her better than ever. Will you please tell the rest?”

“Mr. G. was for a long time ill, and was unable to rest well at night. Polly, who always remained in their chamber at night, was in the habit of rising early, and practising all her accomplishments by herself as soon as she could see. She would begin, ‘Mr. G.,’ and then go on, ‘My dear,’ the name he always called his wife, ‘Francis, Maria,’ until she had repeated the name of every member of the family; after which she chattered away a strange mixture of sense and nonsense until called to breakfast. After the gentleman was so ill, his best hours for rest were soon after dawn, and my friend would whisper, ‘Still, Polly! keep still!’

“This caution the parrot tried to enforce on herself by softly repeating the words away down her throat—‘Keep still; Polly! keep still!’ and ever after until Mr. G.’s death, whenever she saw her mistress point to the bed, and put her finger on her lip, she began to whisper, ‘Keep still, Polly! Keep still!’

“At Mr. G.’s funeral, the clergyman, who was an Episcopalian, read with great solemnity the funeral service.

“The strangeness of the scene, the great concourse of people, and the sound of weeping, so interested Polly that she did not utter a word; but no sooner had the family returned from the grave than she began to utter sounds in sentences so nearly like what she had heard at the funeral, that it was recognized at once as the service for the dead.

“I forgot to tell you that, having been in the habit of hearing the children when they repeated the Lord’s prayer, she had long ago learned it, and never went to sleep on her perch without uttering the words with apparent solemnity.

“After the funeral, whenever a number of persons were assembled and began to talk in a mournful tone, Polly always seemed to think this a proper occasion to repeat her funeral service, often occupying an hour in the recital. There were no distinct words; but the sentences were so similar in length, and the tone so exactly that of the clergyman, that many persons recognized it without being told who the parrot wished to imitate.”

“I think Polly is the very best parrot I ever knew,” exclaimed Minnie. “I wish Mrs. G. would bring her here. I wonder what Poll would say to her.”

“Mrs. G.’s bird is dead, my dear; and a sad death it was too. I will tell you about it. After her husband’s decease, my friend had a little Blenheim spaniel presented her—a beautiful creature, with long white hair like satin, and salmon ears. She was naturally fond of pets, and soon became greatly attached to the dog, who returned her affection with all his heart. As soon as she entered the room, he ran joyfully to meet her, licking her hands, and showing his pleasure in every possible way.

“For some days she noticed that the bird seemed dull, and talked very little; yet she did not connect it with the fact of her attention to the dog. But at last as Polly refused to eat, and seemed uneasy when the spaniel was present, she was convinced that the bird was jealous. Every means was tried to reconcile the old friend to the new one, but in vain. Polly knew that children must of course be loved and cared for. She herself loved the children of her mistress; but she could not endure that any other favorite should divide the affection she had so long enjoyed. From this time she drooped; and upon consulting a physician, he said she had every symptom of consumption. Her feet swelled, and at last she died on my friend’s breast, seeming ‘happy in being allowed to die in the arms of one she so dearly loved.’”

A few weeks later, Mrs. Lee invited a small party of friends to take tea at her house. They were all seated in the parlor, and Poll, who was out of her cage, perched on the back of a chair in the next room, and listened with the greatest curiosity to the hum of so many voices.

Presently one of the ladies related a precious bit of scandal then running through the town. She had scarcely finished her narration, when a shrill exclamation,—

“Possible!” in a tone of incredulity, came through the open doors.

The relator blushed deeply, but went on to prove that her statement must be true, while Mrs. Lee was so much amused, she was obliged to make a great effort to keep from laughing.

Again, as soon as the lady ceased, the exclamation, —

“Possible!” was repeated, as if in greater doubt.

This was too much of an insult, and the lady’s face kindled with anger.

Mrs. Lee quietly arose, saying, “Poll must come in and make her own apology for her rudeness;” and soon returned with the parrot clinging to her finger.

“Poll has a bad habit of interrupting conversation,” she said, playfully, “especially when she wishes to be invited to join the company, as at present.”

“Could that sound come from a bird?” inquired the lady; “I certainly thought it was a human voice.”

Many of the company tried to make Poll talk, but she declined for the present. After a while, however, when some witty remark was made which caused a general laugh, Poll laughed too, both loud and long, and then, as if perfectly exhausted with so much emotion, exclaimed,—

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear me!”

Two or three of the company had been invited to bring their children, and just at this time Minnie returned with her young friends, having introduced them to Jacko and her other pets.

The little girls gathered eagerly around Mrs. Lee, begging her to make Poll talk to them.

“Perhaps you would like to play a game of hide-and-seek with her,” cried Minnie; “she plays that real nice.”

“Yes, oh, yes indeed!” was the united response.

“Come, Poll,” called Minnie, extending her finger.

The parrot went at first with seeming reluctance, but presently entered into the spirit of the play, running after the children around the tables and chairs, laughing as merrily as any of them, and every once in a while repeating that curious “Oh, dear! Oh, dear me!” as if quite worn out.

Minnie then called the little girls into the next room, shutting the door behind them, when Poll, putting her head down close to the crack, seemed trying to listen to what they said. She well understood the game, however, for she presently called, “Whoop,” and then hid behind the door, to catch them when they came along, crying out, as she did so, “Ah, you little rogue!”

After this, she laughed so heartily that none could help joining her,—certainly the ladies could not; but all agreed she knew altogether too much for a bird, and was the most wonderful parrot they had ever seen.

CHAPTER V.

POLL AND THE BACON.

Minnie went one day with her parents to a neighboring town, to visit some friends. She had no sooner alighted from the carriage, than she heard the familiar sound of a parrot’s voice.

“How do you do, miss?” cried the bird, arching its superb neck.

“I am very well, thank you,” answered Minnie, laughing. “How are you?”

“I’m sick, very sick.” The funny creature hung her head, and assumed a plaintive, whining tone. “Got a bad cough. Oh, dear!” (Coughing violently.) “I’m sick, very sick. Call the doctor.”

“I’m glad you have a parrot,” the little girl said to her companion, who stood by laughing. “I have one too; I should admire to hear them talk to each other.”

“Yes, I should; but mother thinks one such noisy bird is more than she can endure. Father had Poll given to him when he was a little boy, and he says he couldn’t keep house without her. She is very old indeed, and is often sick, though now she is only making believe. Father will tell you how many years she has been in the family.”

“There is nothing I like so well,” exclaimed Minnie, enthusiastically, “as to hear stories about birds and beasts.”

“Oh, I’ll get father, then, to tell you a funny one about Polly when he was a little boy. He knows all about parrots, because he once went to the country where they live.”

At dinner, Minnie was introduced to the gentleman, whom she regarded with great interest, on account of his fondness for the bird. No sooner was the dessert brought on the table, and the servants had retired from the room, than Lizzie Monson, her young friend, began.

“Papa, will you please to tell Minnie about Poll finding out who stole the bacon?”

Mr. Lee burst into a merry laugh, but presently said,—

“I warn you it is a dangerous business. Our little daughter has such a passion for birds and beasts, that if she once finds out you are a story-teller, she won’t let you off very easily.”

Mr. Monson gazed a moment into the sparkling countenance of the child, upon which her father’s remarks had caused the roses to deepen, and said, smilingly, “She does not look very savage. Any contribution I can make,” turning to the child, “to your stock of knowledge on your favorite subject will give me great pleasure.”

His bow was so profound and his smile so arch that the little girl could not help laughing as she thanked him, while Lizzie whispered, “Isn’t papa a funny man?”

“Ask your friend to come into the library,” called out Mr. Monson, as they were leaving the dining hall.

“Father, isn’t Poll sixty years old?” cried Lizzie, pressing forward to attract his attention.

“She has been in the family ninety years,” answered the gentleman, “and was then probably one or two years of age. It is astonishing how much she knows. Lizzie, run and open her cage, and bring her here.”

“She is, indeed, a splendid bird,” remarked Mrs. Lee, gazing with delight at her richly-tinted plumage. “See, Minnie, how her neck is shaded from the most beautiful green to the richest mazarine blue.”

“And look at her breast, mother; see those elegant red feathers!”

“The parrot,” said Mr. Monson, “is an insulated bird. Its manners and general structure, and the mode of using its feet, as described by naturalists, are different from any other bird. Mr. Vigors, Mr. Swainson, and others, consider parrots the only group among birds which is completely sui generis. A parrot will, by means of its beak, and aided by its thick, fleshy tongue, clear the inside of a fresh pea from the outer skin, rejecting the latter, and performing the whole process with the greatest ease.

“In climbing, I presume you have noticed, she uses her hooked beak as well as her feet; and in feeding she rests on one foot, holding the food to her beak with the other. Her plumage is generally richly-tinted, while in some varieties, like this, it is superb. In all kinds the skin throws off a mealy powder, which saturates the feathers and makes them greasy.”

“Please, papa,” cried Lizzie, “to tell about these birds as you saw them in their own country.”

“I suppose, Minnie,” continued the gentleman, “that you know this is not the home of your favorite bird. You never see them at liberty and flying from tree to tree, as you do the robin or bluebird.”

“Yes, sir, I know that. Uncle Frank was going to bring me another parrot from South America, but mother thought one was enough.”

“I quite agree with you,” said Mrs. Monson, enthusiastically, “I can scarcely be reconciled to the noise of one, rousing me at all sorts of unreasonable hours, and keeping up such a clatter through the whole day.”

“They are confined to the warmer climates,” the gentleman went on, “and are most abundant in the tropics. I have seen a flock of them resting in a grove of trees, chattering and talking like a company of politicians at a caucus. They are indeed very noisy, keeping together in large flocks, and feeding upon fruits, buds, and seeds. At night they crowd together as closely as possible, and hiding their heads under their wings, sleep soundly. As soon as the first ray of light can be discerned, they are all awake, chatting over the business for the day. First they make their toilet, and in this they assist each other, being very fond of pluming each other’s feathers.

“One peculiarity of this bird is, that he has but one wife, and never marries again. The pairs form lasting attachments, and when one dies the mate sometimes mourns itself to death. They make a kind of nest in the hollow trees, and there bring up their young. They belong to the scansorial order of birds; that is, they have two toes forward and two backward. Some of them fly slowly; but others wing their way with the greatest rapidity, and for a long period.”

“I think,” remarked Mrs. Lee, “they are the most intelligent of the feathered race.”

“Yes, naturalists decidedly give them that character. Poll sometimes seems almost too human; and then they are so quick to learn. Did you know, Minnie, that a parrot is considered an article of delicacy for the table?”

“O, no, indeed, sir! I wouldn’t eat a parrot for any thing.”

“Nor I; but among other rare and luxurious articles on the bill of fare, described by Ælian, as entering into the feasts of the Emperor Heliogabalus, are the combs of fowls, the tongues of peacocks and nightingales, the heads of parrots and thrushes; and it is reported that with the bodies of the two latter he fed his beasts of prey.”

Minnie’s countenance expressed great distress, as she quickly exclaimed, “O, how cruel!”

“Now, papa,” said Lizzie, “please tell her about Poll and the bacon.”

“Yes, I mustn’t forget that. When I was a little boy, Minnie, my father kept a country store, where all manner of things were exposed for sale. On one counter, in the genteel part, were cambrics, calicoes, and even silks for ladies’ dresses, while at the other end were barrels of sugar, boxes of cheese, and other groceries, and above them hung large legs of bacon.

“Midway between these, a hook was driven into the beam, and there Poll used to hang as long ago as I can remember any thing.

“It was the custom for the men of the village to gather together at the store, and talk politics, or gossip about the affairs of the place. Long before town meeting, it was well understood at the store how each man in the community would vote, and who would be elected to the different offices.

“Among others who used to come there, was a man by the name of Brush. He was considered an inoffensive, well meaning man, with no force of character; but all supposed him honest. Poll, however, knew to the contrary; and after a while she convinced others that Brush was a thief.

“It was noticed, when this man got excited by the conversation, that he always left the circle round the stove, and walked back and forth through the store; and it was at such times that he contrived to cut large slices from the bacon, which he carefully concealed in his pocket. My father soon began to conclude that the meat, and sundry other articles, were missing, but could not imagine who was the thief. He watched for several days, not noticing that whenever Mr. Brush made his appearance, Poll instantly screamed, ‘Bacon.’

“One evening he determined to watch, as, the day previous, a larger slice than usual had been taken, and he was hid behind a barrel, when he saw Mr. Brush coming softly toward him.

“‘Bacon! bacon! bacon!’ screamed Poll, at the top of her voice.

“‘I’d wring your neck if I dared,’ murmured the man, glancing maliciously toward the bird; and then he walked back again to the fire.

“After this, father watched the parrot, and found he made this cry only when Brush appeared. He thought it so singular that he charged him with the theft, which the man, in great confusion reluctantly confessed.

“The curious story of his detection by a parrot soon spread through the town, and for years Mr. Brush was called by the name of Bacon, while the bird received much attention and many compliments for her sagacity.”

“I suppose, then, Poll saw him take it,” said Minnie, gravely.

“O, yes! He witnessed the whole proceeding, and did his best to give warning at once; but his loud cries were not understood.”

“Wasn’t he a good bird?” asked Lizzie.

“Yes, indeed. I suppose it would be a good plan to hang a parrot in every store.”

CHAPTER VI.

PARROT SAVING THE SILVER.

Minnie was quite distressed one morning, when, on going to Poll’s cage to say “Good morning” to her pet, she found her unable to answer, only returning a feeble moan. She ran in haste to tell her mother, who thought it one of the parrot’s tricks. When she came down, however, she found Poll was really ill.

“Dear Poll! darling birdie!” she said, tenderly, stroking the beautiful head. “I’ll make you some tea, which I hope will soon cure you.”

She went at once to a side closet, and taking a little pinch of saffron from a paper, sent it to the cook, with directions to steep it at once.

Breakfast that morning was a dull affair, without Poll’s lively talk; and as, after the saffron tea, she did not at once revive, Minnie began to mourn so much lest her dear parrot would die, that her father, to occupy her attention, took her to the library, and read her some anecdotes, a few of which I will repeat.

“A tradesman in London kept two parrots, which usually hung in a cage over the porch projecting from the front door, so that when a person stood on the side of the street nearest the house, the birds could not be seen.

“One day, when the family were all absent, some one rapped at the door, when one of the parrots instantly called out,—

“‘Who’s there?’

“‘The man with the leather,’ was the reply.

“‘Oh, ho!’ retorted the parrot.

“The door not being opened as he expected, the stranger knocked again.

“‘Who’s there?’ repeated the bird.

“‘Why don’t you come down?’ cried the man, impatiently. ‘I can’t wait all day.’

“‘Oh, ho!’ was the only response.

“The man now became furious, and leaving the knocker, began to pull violently at the door bell, when the other parrot, who had not before spoken, exclaimed, ‘Go to the gate.’

“‘What gate?’ he asked, seeing no such convenience.

“‘Newgate,’ was the answer, just as the man, greatly enraged at the thought of being sent to Newgate prison, ran back into the street, and found out whom he was questioning.”

“Dr. Thornton, a benevolent physician in London, once visited the menagerie in Haymarket, where he saw a parrot confined by a chain fastened to his leg. He talked with the bird, and found he could imitate the barking of dogs, the cackling of fowls, and many sounds like the human voice. The bird, however, seemed melancholy and restless, which induced the good doctor to try and buy him of the owner. He succeeded at last in getting him for the sum of seventy-five dollars, which Dr. Thornton did not regret, since it would rescue the poor creature from her present unhappy confinement.

“The first thing he did was to loose him from the chain, and carry him home, where his diet was changed from scalded bread to toast and butter for breakfast, and potatoes, dumplings, and fruit for dinner.

“At first, his poor feet were so cramped, and the muscles so much weakened from long disuse, that he could not walk. He tottered at every step, and in a few minutes appeared greatly fatigued. But his liberated feet soon acquired uncommon agility, his plumage grew more resplendent, and he appeared perfectly happy. He no longer uttered harsh screams, but very readily learned many words, and amused himself for hours repeating them. He attached himself particularly to his kind benefactor, and always cheerfully practised his little accomplishments to please him, calling out, ‘What o’clock? Pretty fellow! Saucy fellow! Turn him out, Poll.’

“He was friendly to the children of the family, and to strangers, but exceedingly jealous of infants, from seeing them caressed.

“He was remarkably fond of music, and danced to all lively tunes, moving his wings, and also his head, backward and forward, to keep time. If any person sang or played a wrong measure, he stopped instantly. When his quick scent announced the time of meals, he ran up and down the pole, uttering a pleasing note of request.

“When any food was given him of which he was not very fond, he took it in his left claw, ate a little, and threw the rest down; but if the variety was nice and abundant, after eating what he wished, he carefully conveyed the remainder to his tin pail, saving it for another occasion.

“Every Friday a scissors grinder came and worked under his window. After listening attentively, Poll tried to imitate the sound with his throat, but could not succeed. He then struck his beak against the perch; but his quick ear discerned a difference. Finally he succeeded by drawing his claw in a particular way across the tin perch, and repeated the performance of grinding every Friday, much to the amusement of those who saw him.”

Minnie was so much interested in these stories that she quite forgot her grief, until her mother opened the library door to tell her that her pet was beginning to sing.

Minnie flew to see her, and before noon had the pleasure of knowing that Poll was quite recovered. Indeed, she had never seemed more gay. She hopped first on one foot and then on the other, in curious imitation of a polka dance, tossing her head on one side in a most coquettish manner.

Then she talked and laughed with Minnie, exclaiming every now and then in a cunning tone, “What are you about, you rogue? O, you little rogue!”

The little girl was delighted. She held Poll on her lap, caressing her fondly, and calling her by all sorts of endearing and funny names.

The parrot on her part seemed desirous of showing her gratitude for relief from pain by doing all she could to please her little friend. She often heard the cook calling Tom, who was apt to run to the barn when she wanted him; and she began in a loud, impatient tone, “Tom!” her voice rising; then again, “Tom!” falling inflection; “Tom!” again; “I say, Tom; come here, you rascal!”

Finding this made Minnie laugh heartily, she began to call, “Leo, come here! Lie down, sir! Tiney, Tiney,” in a small, fine voice, like the child’s; “Tiney, Tiney, Tiney! O, you little rogue!”

After this she chattered away like Jacko, cocking her eyes and looking as if she thought herself very smart.

Once in a while Poll talked Portuguese, which she had learned from some sailors who were in the vessel when she came over, more than fifteen years before. She began now to talk what sounded to Minnie like perfect jargon, but which so much amused the bird that she kept stopping to laugh most heartily.

By and by Mrs. Lee was ready to sit down; and she said Poll had had excitement enough for a sick bird, but told Minnie if she would bring the book about birds, she would try and find some true stories to read to her.

The next hour was passed most pleasantly to both of them. Some of the stories I will tell you.

“A parrot belonging to a lady in England was fond of attending family prayers; but for fear he might take it into his head to join in the responses, he was generally removed.

“But one evening, finding the family were assembling for that purpose, he crept under the sofa, and thought himself unnoticed. For some time he maintained a decorous silence; but at length he found himself unable to keep still, and instead of ‘Amen,’ burst out with, ‘Cheer, boys; cheer!’

“The lady directed the butler to take him from the room; and the man had taken him as far as the door, when the bird, perhaps thinking he had done wrong, and had better apologize, called out,—

“‘Sorry I spoke.’

“The overpowering effect on those present can be better imagined than described.”

“Here is a story,” continued Mrs. Lee, “of a parrot who acted as a police officer.”

“In Camden, New Jersey, Mr. John Hutchinson had a very loquacious parrot, and also a well-stocked chest of silver plate. One day some robbers thought they would like to use silver forks, goblets, and spoons, as well as their rich neighbors, and watching their opportunity broke into the pantry.

“They had already picked the lock off the thick oaken chest, and were diving down among salvers, pitchers, and smaller articles, when they were terrified to hear a loud, angry voice exclaim,—

“‘You lazy rascals, I see you! John, bring me my revolver!’

“Dropping the silver, which they had taken, on the floor, the robbers made a rush for the window, which they had forced open, and in their hurry got over the wrong fence into the yard of a neighbor who kept a fierce dog.

“Bruno, not at all pleased with the appearance of his sudden visitors, sprang upon them, barking at the top of his voice.

“The noise called the police to the place, and one of the robbers was secured.

“The watchful parrot saved his owner’s silver. When he was praised for his timely interference, he would arch his head, and begin at once to call out,—

“‘You lazy rascals, I see you! John, bring me my revolver!’”

CHAPTER VII.

THE PARROT AND THE PRINCE.

“When Prince Maurice was Governor of Brazil, he was informed of an old parrot who would converse like a rational creature. His curiosity became so much roused that, though at a great distance from his residence, he directed that it should be sent for.

“When Poll was first introduced into the room where the Prince sat with several Dutch gentlemen, he instantly exclaimed in the Brazilian language,—

“‘What a company of white men are here!’

“Pointing to the prince, one gentleman asked, ‘Who is that man?’

“‘Some gentleman or other,’ Poll instantly replied.

“‘Where did you come from?’ asked the prince.

“‘From Marignan.’

“‘To whom do you belong?’

“‘To a Portuguese.’

“‘What do you do for a living?’

“‘I look after chickens.’

“The prince laughingly exclaimed, ‘You look after chickens!’

“‘Yes, I do; and I know well enough how to do it,’ clucking at the same time like a hen calling her brood.

“Prince Maurice, as well as the rest of the gentlemen, were delighted with the intelligence of the bird, and after keeping him at his residence as long as possible, the governor gave him a prize for being the most sagacious parrot in the kingdom.”

When Mr. Lee returned from the city, he found Poll as bright and cheerful as a lark. He brought with him a young man in his employ, called Theodore, to whom Minnie exhibited all her pets, and who staid till after tea, and then Mr. Lee read a few stories to Minnie, with one of which I must close my story of Minnie’s pet parrot.

“A prince, named Leo Maced, was once accused by a monk of forming a plan to murder his father, the emperor. He was, therefore, though protesting his innocence, cast into prison.

“After some months, the emperor had a feast, to which he invited most of the nobles of his court. They were all seated at table, when a tame parrot belonging to the prince, and which was hung up in the room, cried out, mournfully,—

“‘Alas, alas! Poor Prince Leo!’

“This exclamation, which was continually repeated, as if the bird could not help comparing their sumptuous entertainment with the prison fare and confinement of his exiled master, so affected the guests as to deprive them of all appetite. It was in vain that the emperor urged his delicacies upon them. They could not eat, while the faithful bird repeated his plaintive cry,—

“‘Alas, alas! Poor Prince Leo!’

“At last one of the nobles with tears entreated the emperor to pardon his son, whom they all believed to be innocent. The others joining in the request, the father ordered that Prince Leo be brought before him. He was soon restored to favor, and then to his former dignities, through the affection of his faithful parrot.”