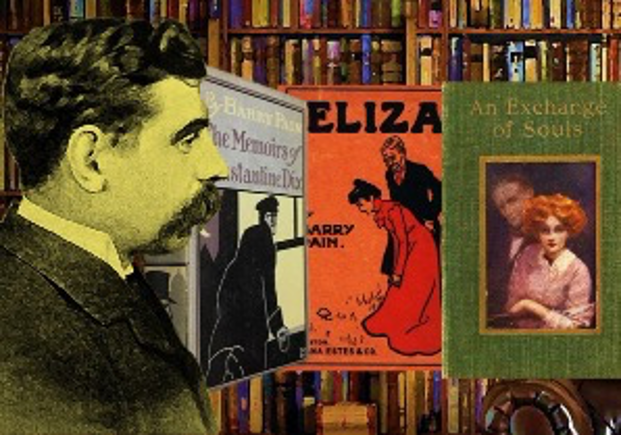

THE GIRL AND THE BEETLE.

By Barry Pain

A STORY OF HERE AND HEREAFTER.

ON the brushwood and groups of trees that here and there broke the monotony of the flat and sandy common were the marks of autumn. The wind was soft and mild, and the leaves fell gently, and the white clouds sailed away into the distance steadily and unquestioningly. Far off the glint of sunlight fell on the narrow, sluggish river. Winds and leaves, clouds and river—all were going home, with a calm meekness that aggravated the dying beetle. It was a good day to die on, and the beetle knew it; but yet he was dissatisfied.

Above him there hovered two unkempt birds, tormented by a sense of what in all the circumstances was the correct thing to do. Each bird had sighted the beetle, and neither would come and take it; for each thought that the other would suppose him to be greedy. Of these two birds the one was magnanimous and the other was nervous, and both were hungry.

“There’s a large beetle down there,” the first remarked, “but I don’t know that I care about it particularly. Won’t you take it?”

There was nothing that his companion would have liked better, but his unfortunate nervousness prevented him from availing himself of the generous offer. “No, thanks,” he stammered, “I couldn’t deprive you.”

“But I really don’t want it,” said Magnanimity.

“Nor do I,” replied Nervousness. “Let’s go for a little fly.”

So they flew slowly away, feeling empty and mistaken, with a sense that the world must be out of joint where there were nearly always two birds to one beetle, and both the birds understood etiquette. And the beetle went on dying.

He had not during his previous life been a good beetle. He was strongly built, and his constitution, which had now given way, had always been considered robust. Female beetles had thought him uncommonly handsome; yet with all these gifts he had not been a good beetle; on the contrary he had been extremely immoral. He lay stretched on the sand by the edge of the pathway, enjoying the warmth of the afternoon sunlight.

“Mary,” he called, a little querulously, “come out.”

It is difficult to understand how the beetle could call without making any noise. It should be remembered, however, that sound is to beetles very much what silence is to us. A certain kind of silence, on the other hand, answers to what we call conversation, and can be varied so as to express all that we can do by changing the tone of the voice. The small female of depressed appearance, who hurried from the shelter of a stone in answer to this summons, quite understood that she had been called querulously. The two unkempt birds should undoubtedly have waited.

“Thomas,” said the beetle who had been addressed as Mary, “I think you called me?”

“Have you stopped crying?”

“Yes, dear; I won’t cry any more, if you don’t like it.”

“You know I don’t like it. Have you got any new ideas?”

“Well, Thomas, nothing that could be absolutely called new, perhaps; but I remember a little story that my poor dear mother used to——”

“Stop!” said Thomas, “you’re a stale, heavy-minded female, and you can get back under the stone. I was going to let you see me die. I shan’t now!”

“Do let me stop!” pleaded Mary.

“No, I won’t!—stay, what’s that pestilential insect creeping towards us?”

“It’s the Dear Friend. He looks small and meagre, but we must not judge from looks, Thomas. Beauty fades.”

Thomas surveyed Mary slowly. “It does,” he said.

The Dear Friend was so named from his habit of calling indiscriminately on other beetles, and excusing himself on the ground that he wanted to be their dear friend. He lived a very good life, and he wanted other beetles to be good. The want was noble, but he had not sufficient tact to conceal it. Some beetles thought him a bore, and did not care to hear him discuss their sins in his plain way. Others, seeing that he knew so little about this life, thought that he might have unusual knowledge of the next. Beetles, as a class, have a tendency towards mysticism. Mary had a firm belief in the goodness and spirituality of the Dear Friend, although she was dimly conscious that he was not clever. She was very anxious that he should have a few words with the dying Thomas.

“You will see him, dear, won’t you?” she said. “You’re drawing near to your end, you know, and it would do you good to experience a word in season. You have been such a bad beetle.”

“I have,” said Thomas, with a chuckle of intense self-satisfaction, “I’ve been a devilish bad beetle.”

The thought of his own exceeding immorality seemed quite to have restored his good temper. “Heavy-minded female, you are become brilliant. Never before have I experienced a word in season. You may stop, and we’ll interview the Dear Friend.”

Mary, like some females of higher organisations, was rarely able to understand the precise value of a satirical silence. Everything was cloudy in her brain, and nothing precise. She had vague ideas that she ought to be good, and that served her for aspirations. She had at least three decided opinions—that her mother had been very good and very kind to her, that Thomas was horribly bad and very unkind to her, and that of the two she infinitely preferred Thomas. She was emotional and rather self-seeking. At present she was very pleased at being praised, and welcomed the little visitor kindly as he crept across towards them. They formed an extraordinary trio even for beetles. It is not generally known that the lower the physical organisation the more complicated is the character. A beetle is as a rule much more contrary and difficult than a man. The character of a tubercular bacillus is so complex as to absolutely defy analysis.

“Mr. Thomas,” the Dear Friend began solemnly, “I am pleased to see you—in fact, I have come a long way with that intention. I had heard that you were very ill and like to die, and I had also heard—you will excuse me—of your past life.”

“Quite right,” said Thomas encouragingly, “I am guilty of having had a past life. Oh, sir, you can’t think how many beetles of my age have had a past of some kind or other. It is true that it was my own life—I have not taken any one else’s, not yet—but still I’ve had it. I feel that deeply.”

At this the Dear Friend warmed to his work, but made a fatal mistake—he grew slightly enthusiastic. Now Thomas could stand no manner of enthusiasm, because it always seemed to him to show an exaggerated conception of the value of things.

“Oh, Mr. Thomas, I am so very glad to hear you talk like that. This is indeed no time for idle compliments, and you recognise the fact. You have the sense of guilt. You see how disgusting, and loathsome, and abominable the whole of your life has——”

Here he was interrupted by a curious stridulating noise which Thomas made, thereby rendering it impossible to catch the remainder of the Dear Friend’s silence. The poor little insect cooled down again at once. He saw that enthusiasm would not do; that he had been taking matters too fast, and that Thomas was a beetle who required to be treated with a good deal of tact. The Dear Friend himself was unable to stridulate, and had sometimes felt the want of it; but it is not a gift which belongs to every kind of beetle. Perhaps it would be as well to show some interest in the process, and then gradually to lead up to more serious subjects. He waited till the last whir had died away, and then he said:

“May I inquire how you make that noise? It is most interesting.”

Thomas knew all about it.

“It is caused,” he answered drily, “by the friction of a transversely striated elevation on the posterior border of the hinder coxa against the hinder margin of the acetabulum, into which it fits.”

“Ah!” gasped the Dear Friend; but he speedily recovered himself. “That is indeed interesting—really, extremely interesting.” He was trying to think in what way it would be possible to connect this with more important matters. “Talking about fits,” he said, “I have just come away from such a sad case, quite a young——”

“I was not talking about fits, sir,” interrupted Thomas, a little irritably. The Dear Friend hastened to agree with him.

“No, Mr. Thomas, you were not. I see what you mean, and it’s very good of you to correct me. I was wrong. I was quite wrong. But you happened to use the word fits, and that suggests——”

“And talking about jests,” retorted Thomas severely, “I don’t think this is the time for them. When you’re calmer, my friend, and have got over your inclination to make sport of serious subjects, you will see this. Please don’t get excited; I’m not equal to it. You come to see me on my death-bed, and when I try to talk about my past life, you wax ribald, and begin to make puns that a school-girl would be ashamed of. I’m sorry for you, sir,—very sorry. Mary, show that bug out. I want to think of my latter end, and he interrupts me.”

“Oh, dear, dear!” said the poor, well-meaning little insect, almost whimpering, “I’m afraid I’ve made a very bad beginning. I didn’t intend to offend you, and I do hope you’ll make allowances. I know I’m not very clever, and I’m very young, and I’ve never had any education to speak of, because I’ve always been going about in my humble way trying to teach others. But I do want to be your really dear friend, and my heart does yearn to——”

“Mary,” said the exasperated Thomas, “I asked you to show that bug out. Will you kindly go away, sir, and drown yourself? I insist upon thinking of my latter end, and I simply cannot do it when you are here.”

“I will go away, if you wish it, Mr. Thomas, but you will let me come back this evening?”

“You won’t be able to come back, if you drown yourself.”

“But I’m not going to drown myself.”

“Well, you said you were, and you ought to, any way.”

“Oh, Mr. Thomas, I never, never——”

“Don’t contradict. It’s excessively rude, especially in a young bug like yourself. You promised to drown yourself, if I’d bequeath Mary to you in my will. You can take her now, if you like, and you may both go away and drown yourselves. I shall be dead before this evening; and if I am quite dead, you may come back. Now go.”

The Dear Friend turned slowly and sadly away.

“Are you going to take Mary?” Thomas called after him. “You can if you like. She’s nearly as fat-headed as yourself, and you’d get on splendidly together. Pray take her. I’m nearly dead, and I don’t want her.”

The Dear Friend made no reply. The wretched Mary was crying again. Thomas had worked himself up to the climax of fury, and was now lapsing from it into a series of chuckles. “Moist one,” he said, turning to Mary, “you don’t love me.”

“Indeed I do,” sobbed Mary. “I love you ever so much too well—but you’re so cruel—and you make fun of a good cause—and you’re going to die.”

“Let us,” said Thomas, drily, “be categorical. You, like most other females, say too much at once. Your remarks must be sifted and answered categorically. Firstly, you state that you love me. Yet you display a lot of wet, horrible emotion, in order to hasten my end. Don’t speak; you know you did;—and you asked the Dear Friend to come and bore me in my last moments; and you refused to sit on his head, or show him out, or stop him in any way. Consequently I had to stop him myself. I had to be almost rude to him. Perhaps you’d better go after him if you’re so fond of him. He’s only half-way across the path, and you’ll be able to catch him up.”

“Oh, Thomas! I’m sure I never——”

“Will you keep quiet? Can’t you see that I’m being categorical? Secondly, you say that I’m cruel. I am, and it’s not my fault. If you and other people were not so abominably heavy-minded, I should not be cruel. You provoke me. You needn’t tell me that you can’t help being heavy-minded. I know that, and I never said that it was your fault; but it certainly isn’t mine. Nothing that I know of ever is anybody’s fault. Thirdly, you said that I made fun of a good cause. You muddler! I love most causes, and hate most of their promoters. Most causes are noble, and most promoters are presumptuous. So far from making fun of the good cause, I did it the greatest service by asking the Dear Friend to seek an early death. That reminds me—you said that I was going to die. So I am, if you don’t mind waiting ten minutes. Why this unseemly haste?”

At this point Mary became all tears and disclaimers. “If you do that,” said Thomas, “you really will have to go. I am about to die, and I intend to die my own way, without any weeping females or dear friends. It’s much the same with you that it is with man and the other lower organisms. The good heart generally goes with a bad head; and if you have a good head, you probably—there, I thought so. Do you see? The Dear Friend on the further side of the path has just been trodden on by a passing labourer. If he’d had a little more head, he would have kept out of the way, and then he would not have died. Intellect is practical: spirituality is not. Now that is very curious, for although I have always been a most practical beetle, I have frequently had strong spiritual desires. For instance, I often after supper yearn to leave this gross and uncomely world, and bask in an impossible hereafter.”

“Ah!” cried Mary. (She liked the ring of his last sentence.) “Those are beautiful words. If only you would always talk like that, instead of insulting those who only come to do you good. I know the Dear Friend made you angry; but then it’s not so much what he said as what he wanted to say that we must think of.”

“Ah, yes, my dear Mary, most moist and muddle-headed, and it is not so much what I am as what I want to be that the deceased bug should have considered. You were born with a wrong head, and so you form wrong judgments. It’s not your fault; nothing’s anybody’s fault. The Dear Friend was good, but it doesn’t matter. I am bad, and that doesn’t matter either. Nothing matters, and I can’t understand anything, and I want to die.”

Thomas threw himself on his back and kicked petulantly. Mary entreated him not to give way to temper; however, he declared that he was doing no such thing: that he was trying to think very fast, and that the action of kicking made it possible to think faster. Suddenly he stopped, and recovered his normal position. “Mary,” he said, “it is clear to me, and I will make it clear to you, that nothing matters. Suppose something had an optical delusion, and the optical delusion died, and had a ghost——”

“But it couldn’t, Thomas.”

“I know that. I am only asking you to suppose it—and the ghost went to sleep, and dreamed that he was dreaming, that he was dreaming——”

“Oh, don’t go on! you’ll only make your poor head ache!”

“Do you think the something would care very much what happened in its optical delusion’s ghost’s dream’s dream’s dream? Yet the innermost of the three dreams would seem to be perfectly real, and the apparent reality would be due to part of the previous experience of the something, which would be filtered—or, rather, reflected—through the whole series.”

“That will do. Please don’t go on. I don’t understand a word of it, and it’s no use. Oh, do let us talk good.”

“You are going to understand it, fat-headed one. You think that you exist; that everything is real. How do you know that it is so? When you dream, you imagine that the dream is quite real; but you wake up and find that you are wrong. Now suppose the something one day had a thought, that went through a million optical delusions, a billion ghosts, and a trillion dreams——”

“It’s not a bit of good,” interpolated Mary. “I can’t imagine numbers like that.”

“That thought might ultimately take the form of this world, of which I, Thomas, the beetle, am a considerable part. There is nothing impossible about that. It may be so, and I am inclined to think that it is so, because something inside me seems to be struggling to get back to its origin. But if it is so it must be perfectly clear to you that nothing matters, because nothing is real, and nothing will be real till it gets back again to the—the something!”

“I don’t understand it,” said Mary; “are you quite sure that it doesn’t confuse you at all to think that way?”

“Absolutely sure,” said Thomas, which was untrue.

“And how do you get back again to the something?”

“That,” said Thomas drily, “I will show you in a few minutes if, as I said before, you do not mind waiting.”

For a short time neither of them spoke. The sun, like the spoiled child who promises to be so good if you will only let him stop, was growing more beautiful than ever as the time drew near for his departure. He had nothing but vapour and light with which to work, and yet he produced some very pretty effects. The gravel path, near which Thomas and Mary were lying, led into the road which skirted the edge of the common; along this road was a line of detached villas. The sun did the best that he could with them, but felt that he could not do much. The last house in the line was much larger than the rest, and stood in much larger grounds. The advertisement had described them as being park-like, and they certainly contained quite enough trees almost to hide the house from the views of those who passed on the road. The sun had found out one of the windows through the foliage and was making it blaze. He liked doing that. He could see a good deal of the house and grounds; in point of height he had the advantage of passers-by. He could see two tennis-courts, the players, groups who had gathered to look on, others who strayed aimlessly about and tried to prove they were not suburban. It was all cup and conversation, and it rather bored the sun, who has a masculine mind. None of the people in that garden were aware that rather less than half a mile from the house a remarkably fine beetle was dying in his sins; if they had known it, they might possibly not have cared.

When Thomas began to talk again, he appeared to be continuing a line of thought of which he had not considered it worth while to give the beginning.

“So the truth of the matter is that a beetle did once get there—right up beyond the stars, but he never carried a man there. Aristophanes said he did, but that was an ætiological myth. He made up the story to account for a prevalent belief that man could rise to higher things.”

“That was what the Dear Friend always said,” murmured Mary reflectively. “Cows, and pigs, and men, and fowls can never get up there—only beetles. It’s all kept for them.”

“And it’s not what I say,” retorted Thomas sharply. “I’ve got better things to do in my last moments than to waste them in agreeing with anybody. The mistake the man made was not in supposing that he could rise. All beasts can rise, as much as we can. His mistake was in rejecting the supernatural, and thinking that he could be raised only by a beetle. We may have more spirituality than men. That is quite possible: they are a lower organism. We may perhaps find it easier to soar than they do. But I am sure that all are going there, just as we are, beyond the stars.”

“That may be true,” said Mary, plucking up a little spirit; “but it certainly was not the opinion of the Dear Friend. Only beetles can rise.”

“Do you prefer the opinions of the Dear Friend to absolute truth?”

“I do,” said Mary proudly.

“Oh, blind and fat of temperament!” [This does not read quite right, but it is a fairly literal translation. There are no polite English words that exactly express the silence which Thomas used on this occasion.] “A few days ago I was down in the grass by the river. It looks sweet and green from here. It grows long, and it makes a pleasant shade above one; but at the roots it’s all mud and muck. That is the way of the world; instead of grumbling at the mud we might just as well be thankful for the grass; however, that’s not my point. The cows came down to drink while I was there. They are nasty, lumpy animals; you can see their slobbering mouths and great yellow teeth as they bend over one to crop the grass. Some beetles get nervous, but I don’t fancy there’s any danger. As one of those brutes stooped down, I looked up and saw right into its eyes. It was like looking into immeasurable distance They were sad, humble, trustful eyes; but there was something in them which signified the consciousness of a purpose in being. That is my point. A poor devil of a cow! it couldn’t have told any one why it existed, it could not even have put the reason clearly in its own mind; but it knew. I am much like the beast. I know, but I cannot say, not even to myself, the reason for my existence. Sometimes I think that if all sounds were in my power, I could get the whole thing out in music. It is a thing which defies ordinary processes and all logical connexion. I see the fading sunlight writing something on the under edge of a cloud; the intellectual part of me cannot read that language, but something else in me reads it, and understands it, and answers it almost piteously. ‘Oh that I might fly away and be at rest!’ And suddenly the conviction is strong in me that I know why I am here, and what I shall be hereafter. In the awful silence of the night that conviction comes dropping down my dark mind like a falling star. In moments of acute dyspepsia I always feel it.”

He grinned pleasantly. He had spoiled his own poetry, and that pleased him. In his former life he had always been trying to make pretty things, and had always broken them up again. The grin passed from him, and he continued:

“Cows, therefore, have souls. You needn’t contradict me, and thrust that omniscient Dear Friend down my throat, because I won’t stand it. I tell you that I saw into their eyes, and I know. If you want to get at the bottom of things, you must leave all ordinary processes, all logical processes. You can’t crawl down that way: you must jump. The people who dare not jump see that you have got to the bottom of things, and comfort themselves with saying that you must have hurt your poor head terribly. Have I hurt my head, Mary? For my intellect is all gone, and the light is fading very quickly. You hate men, I think. Never despise them any more; for they have souls. They cut down the grass, and it dies. They pull the flowers, and they die. They tread on the beetles, and they die. They kill the animals, cut down the trees, and poison the rivers. Where a man comes, death always follows. They are murderers; they are hideously ugly; they make unpleasant noises, and do not understand silences; they are the very lowest of all creatures, but they are on their way to a hereafter. Nothing’s wasted: the very strictest economy is practised.”

“I can’t understand you, Thomas; and I am afraid that you are getting worse. It tries you to talk. Why did you say the light was fading? The sun is still shining all over us. Oh, Thomas, you’ll be gone soon—may I cry now? I must.”

Thomas did not seem to have heard her. “I have been wicked, and yet not I,” he said. “It was something bad in me that will pass. And the world did provoke me terribly; it would be so emotional and stupid.”

Mary was crying unreservedly, but Thomas did not notice it.

“Something,” he said, “has come into my head which wants thinking out, but I will not bother myself. I have the easier way. Good-bye—for the sake of old times—Mary, darling. I am going to know everything.”

Then he curled up his legs quietly, and died.

Mary stopped crying, and examined the body. Yes, he was quite dead. Then she started away on a journey.

Thomas had been a wicked beetle, and he had talked wrongly in his last moments, and she was afraid to be near his body. Besides, she had heard of a vacancy.

The sun had quite finished with the window of that villa now, and the park-like grounds were nearly empty. On one of the courts a few enthusiasts were still playing, and would continue to play until they went in to dress. Out through the gate a young man sauntered into the road. The look of an escaped animal was on his face. He had been talking to a number of people whom he neither knew nor wanted to know. He had seen nothing of Marjorie, his host’s daughter, a child who always pleased and generally amused him. He felt that he had done much for his hostess; he had suffered privations. And now he was glad that the bulk of the visitors—all who were not staying in the house—had gone. He took the path across the common, pausing to light a pipe with a wax match and an air of relief. He walked in the direction of the spot where the dead body of Thomas was lying.

One of the two unkempt birds came slowly flying back again. It was he to whom the surname of Magnanimity has been given. He had got rid of his companion by some pretext of an appointment, and he had come back again to look for that beetle. He swooped down close beside the dead body of the insect, and turned it over with his beak.

“That’s just my luck,” he murmured softly. “I never could stand cold meat.” But that was affectation.

At this moment a small stone struck the ground within a foot of where the unkempt bird was standing. He hopped away in an aggrieved fashion.

“I won’t fly away yet,” he said sulkily, “it would only make the man conceited. They’re always chucking stones, these fools of men, and they hardly ever hit anything. They like to think that we’re afraid of them, and I’m not the least bit afraid.”

Another stone missed by a sixteenth of an inch the bird’s tail-feathers, and Magnanimity with one scream of bad language flew upwards. When he got there, he found that his nervous and unkempt companion had come back again, and had been watching him all the time. Then the magnanimous fowl swore worse than ever. There was no doubt that the nervous one would have a pretty story to tell about that pretended appointment.

The young man, who had thrown the stones, sauntered slowly up and surveyed the dead beetle, taking it in his hand to examine it more closely. He knew something about beetles—he had collected them in his school-days—and he saw that this was a large one of its kind, a fine specimen. He slipped it into one of his coat pockets, and strolled slowly back again to the house. He had originally meant to go further, but he had changed his intention. He was comparing in his own mind his favourite Marjorie, a child not quite fifteen, with the finished and ordinary girl as turned out in large numbers for the purposes of suburban tennis. He was also wondering casually why there were any beetles in the world, and why he had once been so interested in them.

When he got back to the house he paused in the hall for a second, and then went slowly upstairs to a room at the top of the house, used as a schoolroom by Marjorie and her governess, Miss Dean.

Marjorie was seated at the table writing. She had a large French dictionary by her side. She was dressed in dark blue serge. Her long hair had become a little untidy in her struggle to be idiomatic. She had a pale, intelligent face. She looked up as the young man entered.

“I’m awfully glad you’ve come,” she said, smiling. “It was getting rather dull, being all alone. Did you have some good setts?”

“No, not particularly—didn’t play much. I talked, and made myself useful, and ate ices, and drank things most of the time. You can’t see like that.” He struck a match, and lit the gas, and then he seated himself at the piano. “Where’s Miss Dean?”

“Oh, she went away as usual at half-past five, and left me this stuff to do for to-morrow. I’m doing it now, because I am going to be down in the drawing-room to-night. Only three more days to the holidays!”

“Have you got any tea?”

Marjorie nodded her head towards a table at the side of the room. “They brought it up about an hour ago,” she said. “It’s quite cold—will you ring for some more?”

“No, thanks,” he answered, as he got up and helped himself. “This will do very well. I am not really thirsty, because, as I said, I have been drinking during the whole of the afternoon—more or less. But I never feel absolutely sociable unless I am either smoking or drinking. Have you got much more to do for the estimable one?”

“Oh, no, only a few words. It was a shorter bit than usual, and I expected to have got it finished ever so long ago. But when it came to doing it, there were a lot of words that I’d never seen before. I know the French for a plate, or a glass, or a horse, or a hat, or anything like that. But I always have to look up words like buttercup or gridiron. Now here’s a word of that kind. What’s the French for beetle?”

“Escarbot, I believe, but I wouldn’t swear to it.”

“Look here, Maurice,” Marjorie said very earnestly, leaning her pretty little chin on one hand, “I’ll tell you what I’ve noticed. When a thing’s different in one way, it’s always different in another. If a piece for translation is extra short, there are always more words to look up. If I have an awfully bad morning, and Miss Dean is savage, and Aunt Julia patronises me, and Miss Matthieson makes me kiss her—bah!—I’m always glad at the end of it, because I know I am going to have a specially good afternoon or evening.”

“Marjorie, I believe you’re right. You’ll have a bad morning to-morrow if that wretched piece about the gridirons and beetles isn’t done for the inestimable Dean.”

“Well, I’ll finish in less than two minutes. Play something while I’m doing it.”

He opened the piano and took down the first piece that came. It was a drawing-room piece, and had the entire absence of soul which always appealed to the corresponding vacuum in the chilly Miss Dean. It was moderately difficult, and sounded very difficult. Miss Dean well knew that when a girl like Marjorie, not yet fifteen, played that piece properly, it would be acknowledged to reflect great credit on her teacher. Maurice Grey opened the piece, looked at it suspiciously, skipped the introduction, played a few bars from the first page, glanced at the fifth page, then shut it up, and put it back again on the top of the piano with a sigh.

I hate that too,” said Marjorie. “Play the thing you played to them last night in the drawing-room.”

“You weren’t in the drawing-room last night.”

“No, but my bedroom’s just above, and I could hear it. It went like this.” She hummed a few bars.

Maurice began to play once more. It was a mischievous, tender, eccentric little dance that went laughing about the piano as if it were mad. Marjorie had finished her work, and rose from the table and stood beside him, watching him with dark, attentive eyes as he played. She was thinking that she liked Maurice. He knew the right way to treat her. Aunt Julia treated her like a baby, and other visitors often appeared to be under the impression that children like inanity. Her father was rather an apathetic man, yet he had the sincerest affection for his wife, his only daughter, and young Maurice Grey. He had many acquaintances, but no other friends. He had been “Meyner and Sons,” who did great things in iron, but he disposed of his business to a company soon after his marriage. He was absorbed in the study of psychology, and made many curious experiments upon himself. In one or two of these young Maurice had been of some service to him. But in his family affections, his studies, or his experiments, he showed very little enthusiasm. He never expected to get great results. “The evidence is so bad,” he said to Maurice once, speaking of his favourite pursuit. “On my subject men lie often intentionally; and often deceive themselves and lie unintentionally, and rarely speak the truth. Also I find out more and more that I cannot even trust my own senses. The human brain is a shockingly defective instrument.” He was a little sensitive, and to visitors in his house—with the exception of Maurice—he would talk of anything but psychology. Psychology, he found, was a thing they never understood at all, and at which they generally laughed. Marjorie’s mother, Mrs. Meyner, was not so apathetic or so pessimistic, but then her horizon was not extended. The circle of her friends and relations gave her enough to think about and to make life worth living. She was a very gentle, unselfish woman, and had a provoking knack of sincerely liking nearly everybody. Her half-sister, Julia, had the opposite knack of hating nearly everybody. Julia was old and unmarried, and had a wonderful tongue; she dressed perfectly, had snowy hair, a kind face, a sweet smile, gentle ways, and a perfectly venomous disposition. Marjorie did not like her Aunt Julia. She did not like Miss Matthieson much better—a sentimental woman. Miss Dean was too chilly a person to like exactly; Marjorie respected her sometimes. But she did like Maurice, and she liked the music that he was playing now.

“That is awfully nice,” she said, when the piece was finished. “What is it?”

Marjorie’s aunt Julia had asked the same question of him the night before in the drawing-room, and he had told her that the piece was by Grieg, which was untrue, and which he knew to be untrue. He was not aware that that cheerful, spiteful, and horribly intellectual old lady also knew that he was lying. He had felt it better to blaspheme the name of Grieg than to give her a chance by owning that he had composed the thing himself. He was a young man of dangerously diverse talents. He was just at the end of his first year at Cambridge, and was reading for the Classical Tripos. Now the Classical Tripos is a jealous mistress, and admits of no rivals. Nevertheless, he had become a very fair oar, was socially popular, and had devoted much time to psychology and more to music. The end of such a course is generally failure. He did not mind telling Marjorie about the little dance he had just been playing.

“Well,” he said, “I have a general impression that it is mine; but there’s a touch of Grieg about it. In fact, I risked telling your aunt Julia last night that it was Grieg’s. I daren’t tell her it was mine.”

“Yes,” said Marjorie sadly, “she is awful. She pats me gently on the head, and tells me I’m a good little child, and that I may run away to the nursery and play. It’s perfectly maddening. She knows as well as I do that I’m nearly fifteen, and that it’s absolute nonsense to talk like that. She does it on purpose to make me angry, and I hate being angry.”

Maurice took a long sip at his cold tea.

“Yes,” he said, “the people in this world want sorting. Have you finished your piece about the beetle and the gridirons?”

“Oh, yes! There’s nothing in it really about gridirons, but a beetle comes into it—a dead beetle——”

“By Jove!” said Maurice suddenly, thrusting his hand into his pocket, “that reminds me!” He pulled out the dead body of Thomas, and laid it carefully on the table.

“There,” he said, “what do you think of that?”

“It’s perfectly horrible,” said Marjorie. “Where did you get it? What did you do it for?”

“I strolled on to the common after tennis for a smoke, and I happened to find it. I used to collect these things when I was at school. I suppose I picked it up from force of habit, but I’m sure I don’t know. You ought not to call it horrible, you know. It’s really a fine specimen of its kind.”

Marjorie looked at it more closely, turning it over with the end of a penholder.

“Do you remember saying just now,” said Maurice, “that things which were different in one way were generally different in another? Beetles are different from us; they can’t do the same things; we despise them; they haven’t as good a time. Perhaps they can do things we don’t know anything about; perhaps they despise us; perhaps they are going to have a better time in some other world. What are all the stars for?”

Marjorie wrinkled her brows, and kicked one tiny slipper half off.

“I almost think I see what you mean——”

“I am not at all sure I meant anything,” said Maurice. “It was just a suggestion.”

Marjorie had thrown down the penholder, and taken the body of Thomas in her hand.

“Beetles might have some secrets that we know nothing about. But Miss Dean says that all insects were sent into the world for the birds to eat.”

Maurice was silent for a moment. He was remembering that Miss Dean had remarked to him the day before that she considered that the birds had been created to kill the insects. “I should like to talk the question over with a beetle. Now I must be off and dress.”

When he had gone an old trick of Marjorie’s younger days came back to her. She had often, in her babyhood, held conversations with voiceless or inarticulate things, such as dolls or cats, and on one occasion, after a stormy music lesson, she had made the piano promise to make the music come out right next time. She had always to do the speaking for them, so it was not quite convincing; but it was helpful and consolatory in its way. And now she began to talk to the beetle aloud, holding it on the palm of one little white hand—

“Beetle, tell me your secrets. Tell me all your secrets.”

There was silence.

“I want to know if beetles are as good as men. Are they? Are they better than men? Are there better things than we ever think of doing, which we might do if it was only possible to think of them? Do tell me. I won’t tell anybody, except Maurice and mamma, if she asks me, but she won’t. You might tell me—it’s quite safe.”

There was only silence; but then it has been proved already that silence is a beetle’s method of speech. Perhaps the spirit of Thomas was there and answered her; perhaps it was elsewhere; perhaps Thomas never had a spirit.

Marjorie put the beetle down again on the table, with a laugh at herself for her silliness.

In the drawing-room that night, she saw very little of Maurice. Aunt Julia looked as perfect and sweet and gentle an old lady as ever; and her conversation was just as poisonous as usual. Her temper must even have been a little worse than normal. She commenced to talk about psychology with Mr. Meyner, because she knew that he hated discussing it with the uninitiated. She insisted that he was joking—the poor man never joked; he was half earnestness and half apathy—and she told him untrue stories. When he escaped, she fastened on to Miss Matthieson, who was a sentimental and ignorant woman, with a desire to love art. She invented an entirely fictitious picture of Turner, described it, and gave its precise position in the National Gallery; she finally made Miss Matthieson talk about it, become enraptured about it, and confess what her sensations were when she first saw it. She did not enlighten her; that would have been too crude an enjoyment for Aunt Julia. Her smile became just a little sweeter, and she assured Miss Matthieson that she had learned much from her. Maurice Grey had, for reasons of his own, been playing Chopin’s Funeral March. “And is that also by Grieg?” she asked him, looking interested.

“No, it is not,” he said shortly. He knew very well that Aunt Julia knew very well what he had been playing; and he saw what she meant by her question.

“Oh, please don’t be angry with me,” she said. “I’m no musician, you know, Mr. Grey,”—her knowledge of music was, as Maurice was aware, considerably above the average—“and I make stupid mistakes. Last night you played a little dance which you told me was by Grieg. Now, I never should have known it; I thought it was pretty enough, but just a little weak and—well, almost amateurish, you know. You played it again in the schoolroom this afternoon, and you altered the last part of it. What is that thing you played just now?”

“Chopin’s Funeral March.”

“Are you going to make any—any improvements in it, as you did in the Grieg? And why did you play a funeral march? I suppose the sight of an old woman like myself, among so many young people, suggested the thought of death. Ah, yes—very natural.”

This was absolutely intolerable, but Maurice was not allowed to protest or escape.

“It is a great mistake,” said Aunt Julia, earnestly, “to give one’s self up to trivialities. We must all die. It is always better to think about death, even in the drawing-room after dinner. I mean that it’s better for the aged, like myself. To the young it might perhaps seem a little gloomy and morbid, but I like it—I enjoy it. I shall be going to bed directly. Won’t you play a few hymn tunes, Mr. Grey, before I go? You might play the Dies Iræ.”

She did not go to bed until she had maddened about half the people in the room. Even Mrs. Meyner found it difficult at times to make excuses for Aunt Julia. Maurice Grey managed to be moderately polite to her as a rule; he generally shammed stupidity, and refused to see the point of any of her sarcasms. He found afterwards that this style of treatment had impressed Miss Julia Stone. When Marjorie came round to say good-night to Maurice, she spoke to him about the beetle.

“Do you want that dead beetle?” she asked. “Shall I keep it for you?”

“Yes, keep it.”

“Are you going on collecting again then?”

“No, I don’t think so—but it is too good a specimen to throw away just anywhere. How would you like to be thrown away?”

“It’s not quite the same thing, you know, Maurice. I’m more important. But we’ll treat this beetle very well—you’ve just played a funeral march for it—and then, perhaps, its ghost will come and tell us all about beetles, and what beetles think about men, and if they know anything that we don’t.”

“Yes, treat it kindly,” said Maurice, smiling. “Much can always be done by kindness.”

Marjorie went out of the room laughing; but on the following morning, when she appeared at breakfast, she was very quiet and subdued. A note came from Miss Dean, regretting that—“owing to a slight indisposition”—she was unable to come to teach Marjorie that morning. Even the prospect of a day’s holiday did not seem to cheer her up. Maurice found her alone in the garden about an hour afterwards.

“What’s up, Marjorie?” he said. “Aren’t you well?”

“Oh, yes, I’m always well—I’ve got something to tell you though. I saw it last night.”

“Saw what?”

“The beetle.”

Maurice was a little startled. He too had had a curious dream in which the beetle had figured. “Look here, Marjorie,” he said; “I’ve nothing particular to do this morning, and I believe you’d be the better for a walk. We’ll go over to Weyford, and then go up to St. Margaret’s, if you don’t mind climbing the hill.”

“Oh, that would be lovely! That’s just the thing. We shan’t get back to lunch, you know.”

“That’s all right. We’ll lunch in Weyford. I’ll go in and talk to Mrs. Meyner about it, and you go and get ready.”

The morning sunlight and the cool wind made walking pleasant. That unkempt bird, whom we have called Magnanimity, was taking out quite a young bird for a little exercise. They saw Maurice and Marjorie walking together.

“Those are men,” said the young bird. “Bless your heart—I’ve seen lots of ’em.”

“Just drop that,” said Magnanimity, sternly. “There’s nothing more sickening than to hear a mere chick like yourself setting up to be a complete bird of the world. Fancy taking any notice of contemptible, ugly men!”

“That young she-man,” said the mere chick, “isn’t at all ugly. I often wish I were a man.”

“You’d soon wish you were a bird again,” retorted Magnanimity. “Are you aware that men can’t fly, or lay eggs, or talk our language, or do anything really worth doing? Are you aware that we old birds lead them the very devil of a life?”

“How do you do it?” asked the mere chick, quite unable to keep the wonder and admiration out of the tone of its voice.

“Why, we mock at ’em—sneer at ’em till they can’t bear themselves.”

Marjorie and Maurice walked on, talking of indifferent things. They climbed the hill, resting occasionally in the shade of the plantations that grew on its sides. They reached the summit at last, a solitary place where the ruined chapel of St. Margaret stood in a little deserted grave-yard. The wind was fresh and cool. They could see far away into the distance; they could see the river winding along down the valley, until it was a mere thread of silver; they could see the smoke curling up from low, red-roofed cottages and farm-buildings, scattered here and there. Maurice stretched himself at full length on the grass, and endeavoured to light a cigarette. There was just enough wind to blow a match out. There always is.

“Now then, Marjorie, you had a dream last night.”

“Yes!”

“And it frightened you.”

“No—no—well, it didn’t exactly frighten me—it made me think. It was all nonsense, you know, and yet it was the realest dream I ever had in my life.”

“Stop a minute. You had some coffee in the drawing-room, and that kept you awake for a long time, you turned about from side to side, and thought about the beetle. Your bedroom seemed hot and stifling.”

“Yes, that’s all true—how did you know, Maurice?—but it has not got anything to do with it.”

“Marjorie, if you’d never had that coffee, you’d have never had that dream. Now, then, let’s hear it. I’ll try to keep awake, but walking always makes me sleepy.”

“After I had said good-night to everybody, I went up into the schoolroom and got the beetle, because I was afraid the servants might throw it away in the morning, and you said you wanted it. I took it into my own room, and put it down on a table. All the while I was undressing, I kept thinking about it and wondering if beetles and other things could really understand, or if it were only men and women who knew about things, and if all the world were just made for us alone. Before I got into bed I picked the beetle up, and said to it, ‘Beetle, you’ve got to come into my dream to-night, and tell me all about it. Don’t forget.’ Of course that was just a fancy. I didn’t really think it could understand what I said, or that it would come. I’m not a baby, though Aunt Julia treats me like one sometimes. Well, for a long time I couldn’t get to sleep, but at last I did.”

“And then the beetle came and suffocated you, or threw you over a precipice,” remarked Maurice, drowsily.

“No, that’s not a bit like it. I don’t know how long I had been asleep, but I dreamed that I woke up suddenly, and that the moonlight was streaming in at the window. Right in the middle of the moonlight was the beetle, standing up on his hind legs. He had grown ever so much bigger, and was as tall as I am. ‘Come on, now,’ he said. ‘How much longer are you going to keep me waiting? I’m late, as it is.’

“I didn’t feel the least bit afraid of him. I just asked him where we were going. He opened the window, and pointed upwards. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘you must wait till I’m dressed, else I shall catch cold.’ However, he wouldn’t wait, and so I got out of bed. We climbed up on to the table in front of the window. ‘Now then,’ he said, ‘you must keep hold of my fore-leg, or you’ll fall.’ We didn’t fly or walk; we floated out of the window, and then upwards, going very quickly and steadily, as if a wind were blowing us. As we were floating up, the beetle’s head changed till it became just like Aunt Julia’s. ‘Marjorie’s an unnatural child,’ it said in Aunt Julia’s voice. ‘She doesn’t care for dolls—doesn’t care for anything except music and Maurice.’”

Maurice had an unworthy and needless impression that the girl was making some of this up. He looked at her curiously, as though he were going to say something; but he refrained, and she continued her dream—

[“I didn’t quite know what to say, but I told the beetle that he was entirely wrong—that I liked papa and mamma very much indeed, and rather liked almost everybody. Then I asked him how he managed to speak, being a beetle, and how he could hear me speak. He told me that neither of us had spoken a word: when I contradicted him, he said that if I had gone back to my own room I should have found that my real body was still lying asleep in bed. ‘Now,’ he pointed out, ‘you can’t speak without your body—so that is proved.’ Then he said that beetles never spoke, and that as a matter of fact we were not speaking, but just understanding each other’s silence. Still, it seemed just like speaking. We must have moved very quickly, because by this time we had got quite beyond the moon. I could see it ever so far beneath my feet, and the stars all scattered about the darkness; yet I didn’t remember passing them on our way up. I didn’t feel at all cold. As the beetle went on talking—it was just like real talking, so it doesn’t matter whether it was real or not—he stopped being like Aunt Julia. He got his own head back again, and his own voice—except that sometimes it began to be rather like yours. You haven’t gone to sleep, have you?”

Maurice had not gone to sleep, and said so.

“The strangest thing was that although his body had not really changed—except that it was so much bigger—it didn’t seem at all ugly now. In fact, I liked to look at it, and didn’t at all mind keeping hold of its fore-leg. I think the beetle must have known what I was thinking about, for all of a sudden he said, as if he were sorry for me: ‘Poor Marjorie! Poor little Marjorie! They’ve taught you all wrong, and they taught me all wrong. But I had a glimpse of the right thing: I always knew that human beings were not half as ugly as they seemed to be. I said as much, but it was of no use to talk to the Dear Friend. As for Mary—that fat-headed female had believed so many other things that she had no capacity left for believing any more. I, however, had got plenty of room left—oh, yes, plenty of room.’ When he said that he chuckled in the most horrible way you ever heard. ‘Now I come to think of it,’ he went on, ‘I believe I did say that the human breed were ugly. It was such a tame thing to believe anything that one said; it was a thing that Mary always did, and so I didn’t. Marjorie, if the good people hadn’t been good, I should have liked goodness.’”

“But who were Mary and the Dear Friend?” asked Maurice.

“I don’t know any more than you do. I don’t think he liked the Dear Friend very much; sometimes he seemed to hate Mary, and sometimes he seemed to love her and pity her. Now do you know what he told me? He said positively that all beetles believed that they had souls which never died, and that the sun, and stars, and everything were made for them alone. They believed that men, and other animals, had no souls at all. I told him how very absurd that was, and tried to explain to him what was really the case; but he only chuckled horribly again. But as we went up higher and higher he got more grave, and he didn’t laugh any more; and once or twice he said to me quite sadly, ‘Poor little Marjorie, you are very young to bother yourself about these things. You only know part—only part—and I cannot tell you the rest—I may not!’ I began to get quite sorry for him, because it seemed to trouble him; I think he really wanted to tell me some more things. Just then I saw up above us a River of Light. It was flowing very swiftly and smoothly, and looked like melted gold. I don’t know why, but I wanted to plunge into the River. It seemed to be the only thing worth doing, or that ever had been worth doing. I never wanted anything so much before in my life, but the beetle would not let me go. Last of all I began to cry; I really did, and you know, Maurice, that I hardly ever cry. But it was of no use; he still kept tight hold of my hand. The darkness was all grey darkness, except one black piece which stuck up like a mountain. We stopped on the top of it, and looked down at the River. I kept on crying—I do not know why, but I think it was because it all seemed strange and awful. I may have been frightened a little, but it was not quite like being frightened. There was a long pause, and then the beetle said, ‘Ah, if you only knew now, Marjorie! And if I had only known then!’

“Just then out of the grey darkness came a thread of light, like a little snake, moving very quickly and curling about as if it were glad; it hurried towards the great River of Light, and melted into it and was gone. I was eager about it, and asked the beetle what it was. ‘I may tell you that,’ he replied. ‘It was a soul going home!’ I stopped crying then; I felt something the way I feel at an evening service in a church in summer time, when they are singing one of the hymns I like best. It was a sort of quiet happiness; I can’t explain it properly, but I never felt so happy as I did then. ‘Beetle,’ I said, ‘you must tell me the rest now.’

“‘I will tell you one thing,’” he said.

“What was it?” asked Maurice quickly.

For a few seconds Marjorie did not answer. There was a queer dreamy look in her eyes. At last she said,—

“Maurice, I’m afraid you’ll think now that I have been making all this up, but I haven’t. I can’t tell you what the beetle said, because I don’t know. It was about you, and it was very important. I don’t even know whether it was good or bad. It has gone straight out of my memory, and I can’t get it back again. I’d give anything to be able to remember it. I’ve been thinking about it all the morning.”

“I believe you entirely,” said Maurice thoughtfully. “I have had much the same kind of thing happen to me in a dream.”

He did not add that much the same thing had happened to him on the same night. “How did the dream end?” he went on.

“I awoke directly after the beetle told me that thing that I have forgotten. It was broad daylight. But when I got up, the beetle was not on the table where I had put it. I could not find it anywhere.”

“You probably moved it in your sleep. Did you ever walk in your sleep?”

“Once, when I was quite little—almost a baby. I had got out into the garden, and my nurse found me there.”

Maurice rose, and the two went down the hill together. “I wouldn’t trouble about all that if I were you,” said Maurice. “These things can generally be explained in the simplest way when one goes through them carefully. Coffee, the action of the heart, the position of the body in bed, the sounds that one hears while asleep, all help to explain a good deal, you know.”

He did not tell her his own dream. He thought, perhaps rightly, that a young girl, unacquainted with the study of mathematics, might be unduly impressed by coincidences which were unusual but did not require a supernatural explanation. He did not want to frighten her, or let her grow superstitious. Yet during the day he thought a good deal about the two dreams.

He had dreamed that he was seated on the one side of the fireplace in his rooms at Cambridge, and that the beetle, with the same exaggerated dimensions with which Marjorie had seen him, was seated in a lounge chair on the other side. They were discussing Maurice’s psychological studies, and Maurice was describing to him some of the curious experiments which he had made in conjunction with Mr. Meyner. Every difficulty that Maurice propounded the beetle made clear at once. He even suggested fresh problems which had not occurred to Maurice before, and was equally ready with their solution. His last words before Maurice awoke were: “There are many things besides which you ought to know, and of which you have not realised your own ignorance. You will know them all one day.”

This was all that Maurice could remember of his dream. The difficulties propounded and the explanations given had passed completely out of his recollection. He was only conscious that during his dream he had felt an exhilarating sensation of having known for certain things which he had thought it impossible that any one, at least in this life, could know at all.

Shortly afterwards he returned to Cambridge. By this time Marjorie seemed to have recovered her normal spirits. She made no further allusion to her dream. She was unaffectedly sorry at the departure of Maurice.

Maurice had not been long at Cambridge before he received news of the sudden death of Mr. Meyner. Apart from the friendship he had always felt for Mr. Meyner, the death seemed to him peculiarly distressing and pathetic. The man had worked hard at a study which fascinated him, not from any desire for gain, or fame to be derived from it, but with the most genuine devotion to the study itself; and he had died before his work was done, before he had arrived at any large and definite result. Yet Maurice felt assured that Meyner’s patience, and judgment, and freedom from prejudice, would, if he had but lived longer, have brought him some reward, some light. He had always distrusted and undervalued himself; his humility was genuine, but almost irritating. He had been at school, and subsequently at college, with Maurice’s guardian, and had first met Maurice when he was a boy of fifteen; the friendship between the boy and the middle-aged man had formed slowly, but surely, since then; yet, although he gave every sign of his liking for Maurice, he never seemed to expect Maurice to like him in return; he certainly never realised the admiration which Maurice had for his knowledge and attainments. So too he loved his wife and only child dearly, and he knew that they loved him; but he had never realised how much they loved him, and would very possibly have thought such love almost irrational. To some extent, perhaps, his studies had spoiled him; he had been groping in the darkness after great things, and the one result that he seemed to have found there was a sense of his own insignificance. Yet, illogically enough, he had never thought others insignificant; he had never reached the cynical conclusion that nobody matters very much. If his friends and his sympathies were so few, it was not because the outside world did not matter to him, but because he could not believe that he mattered to the outside world. He had died without ever having learned his own value.

A parcel which was forwarded to Maurice from Mrs. Meyner shortly afterwards contained the many note-books which her husband had filled with the evidence he had collected, and the work he had done, until death interrupted him. With them was a simple and pathetic letter that he had written to Maurice on the day before he died. “Look through them,” the letter said, in reference to the note-books. “You will see and understand what I was aiming at. If you think it worth while, carry on the investigation which I began; I own that it is some pleasure to me to think that it is possible that you may do so; that one who was intimate with my views, and who shared some of my opinions, which are not generally held, may be able to give those views and opinions their justification. But I do not want you to pledge yourself in any way, nor do I ask you to give up your tripos or your career at college for the purpose.”

Maurice paused as he read this last sentence. How often he had thought, as he turned English verse into indifferent alcaics, that this classical work could only lead, was only educative, could never be considered as an end. But he came to no final decision until he had spent nearly a month in a rapid survey of those note-books. They startled him; the minute accuracy and patience shown in the collection of evidence were only what he expected from such a man as Meyner, but the brilliant audacity of his theories, the almost savage independence of an original mind, looked far different when plainly stated in black and white, than when they had fallen humbly and almost hesitatingly from the man’s own lips. The romantic side in Maurice’s character was touched most by what was worst in Meyner’s books; the finished and unprejudiced scholar would have shaken his head over much that looked like vain imagining, that was extravagant, and, so far, unsupported. Maurice was younger; Meyner’s fierce opposition of an accepted view attracted him, and awoke his pugnacity. He would linger over page after page of what seemed to him splendid conjecture, of what might have seemed to others very useless stuff, and say to himself: “If only one could prove that this is so, instead of longing that it may be so!” The air of conviction with which Meyner wrote down his own views on his own subject gained immeasurably in Maurice’s eyes from the personal knowledge which Maurice had of Meyner’s perpetual tendency to undervalue himself, and to distrust himself in all other matters. Even with these views in his mind, he had expected no great results; he had been too honest to support them with any evidence that was not thoroughly tested. They seemed to Maurice to be the guess of genius; the air of conviction had for him the strange attraction of a religious, not wholly rational, faith. He decided to abandon his University career, and to devote his time to a further prosecution of Meyner’s investigations.

His guardian, who was also his uncle, made very little opposition. Maurice had given so much evidence that he was stable. He had an unusually large allowance for a young man at Cambridge, and yet he had not run into debt. At Cambridge the wealthy are the most in debt, because they have most credit and most temptations. As a matter of fact, Maurice never had considered the financial side of anything; it had simply happened that he had never wanted more than he could well afford. But this weighed very much in Maurice’s favour with his guardian. He felt that his nephew was a man who understood value, and could be trusted. The property to which Maurice would succeed, when he came of age, made it unnecessary for him to adopt any profession; nor did it bring with it any of those special responsibilities for which a special training is supposed to be necessary.

Maurice, therefore, spent the next two years abroad, for the most part in Paris. He had carried with him an introduction to a physician at one of the Paris hospitals, who sympathised with him in his work, and was able to be of great assistance to him. In this man he gained a friend; in other respects these were years, it seemed to him, of disillusion. One by one the great, beautiful theories had to go; a tiny meagre fact would start up, a fact that meant but little to the ordinary observer, and it would be strong enough to overthrow years of work, and send the conjecture on which they were founded to some limbo for lost absurdities. He had long ago been aghast when he had tried to realise how vast is the amount of the things that no man knows. And now for “knows” he put “can know.”

Mrs. Meyner and Marjorie had also been abroad, but he had seen them very seldom in those two years. Marjorie seemed to be slowly changing; he was no longer the recipient of childish confidences. She was grave and more beautiful, perhaps, than she had been; and she was also more quiet and reserved; she was friendly with him, up to a limit; she told him news, of a kind; she sympathised with his disappointments in his work, within decent bounds. At the end of the second year, when Mrs. Meyner and Marjorie were staying for a few days in Paris, and Maurice was at last awakening to the fact that he could not expect childish confidences from one who was no longer a child, Marjorie told him some news which surprised him.

“Aunt Julia has changed very much. I like her now.”

“She must certainly have changed then,” said Maurice smiling.

“I don’t mean,” Marjorie explained, “that she is different to other people—only to mamma and myself. Her servants are in terror of her, and her tenants hate her, and so on; but she has been really kind to me. I think she likes me. We were staying with her a few weeks ago. You’ll be surprised to hear that she likes you too.”

“Of course,” said Maurice, “it is surprising that any one likes me, as you say.”

“I don’t think I said that. She told me quite suddenly once that she liked Maurice Grey, because he was the cleverest man she knew in one respect. Mamma suggested that it was because you understood her. ‘No, my dear,’ said Aunt Julia, ‘the village people do that, because I speak plainly, and they try to pay me back again for it. He always misunderstood me. I like him. He will not do much, because he can’t concentrate himself on one thing; but I like Maurice Grey all the same.’”

Marjorie did not repeat any more of Aunt Julia’s conversation; but the old lady had gone on to say that Maurice, however, would probably concentrate himself on one person. She added, in her point-blank way, that she intended him ultimately to marry Marjorie. She did not appear to think that Marjorie, or Maurice, or Mrs. Meyner, could have a voice in the matter; the marriage was one of the things that the perverse old woman had made up her mind to arrange.

“I’m glad that dear old lady likes me,” said Maurice. “I always liked her—I really did. She was full of such striking and impressive contrasts—the soft, purring voice and the ill-tempered words—her gentle, peaceful face and her fearful pugnacity. And I like her more because she has been good to you, you say.”

“Did you ever,” asked Marjorie, hurriedly going to another subject, “find out anything new about the intelligence of the brute creation?”

“I think I used to tell some lies about a favourite terrier of mine once, and made myself believe them. No, Marjorie, that has not been my line. It has been quite enough to find out that I and you, and all the rest of us, have got no intelligence worth mentioning, none that will do a thousandth part of what we want it to do. What made you ask that?”

“I was thinking about that beetle you found on the common when you were stopping with us once, and about the dream I had.”

“Ah! I remember that.”

“I never found the dead beetle, although I hunted everywhere for it, and I never remembered what it told me about you.”

“I did not tell you at the time, Marjorie, but I had a dream about the beetle that same night. It came to me that night and told me everything I wanted to know—the things I have been working at for the last two years. Of course, they were all gone when I awoke, but I can remember it saying that I should know them all one day. I am afraid that dead beetle lied.”

“Maurice,” said Marjorie suddenly, “sometimes a thought flashes across my mind that in a minute I may be dead. I don’t know even what life and death mean; yet I have to live and die. There are stars above me, but I do not know why they are there. There are beasts, and birds, and insects everywhere, and I do not know how important they are. I feel lost and horrible. No, I feel like a prisoner beating against an iron wall. For a few moments it is torture to be like that; I should kill myself or go mad if it went on. But it always passes away, and three minutes afterwards I am wondering if I will do my hair a different way——”

“Don’t!” murmured Maurice, softly.

“Or I can be really angry because my maid knocks something over, or does something clumsy; when one speaks of it, it seems absurd enough. Speaking spoils everything. Lovers—in books, I mean—talk the worst nonsense, and yet that nonsense is the expression of a very fine thing. I do not think that silence is enough appreciated. I want, for instance, to let you know what I am thinking. Well, when I put the thought into words, I lose some of it, or add something to it, or I alter it by an accident with the tone of my voice. Now if I could just look at you and you at me, and we could understand one another exactly through silence, it would be splendid.”

Maurice agreed with her. After two years of disappointment silence seemed to him almost the only thing left. There was, however, one thing even more consolatory. About a year after this conversation with Marjorie the two met once more, and Maurice put his failures behind him and told Marjorie that he loved her. So they both spoke the nonsense which they deprecated. We all believe that in affairs of the heart we are not as the others, and we are all mistaken. With him there was an iteration of “I love you,” with a deep tremble in the voice; and with her there was a sighing echo of the same words, coming up between blushes. The expression of the feeling was almost ludicrous; the feeling itself was so sacred that the lightest touch of thought seemed to soil it, and a writer, after turning over his vocabulary in disgust, can find nothing explanatory which at all matches it. But when it took place, it seemed to Maurice the only important thing that ever had happened to him; the psychological studies, which had brought him so much disappointment, appeared in a new light as a plaything that had seemed to amuse him until love came.

This did not happen at Paris. Maurice had returned to England, and all of them—Mrs. Meyner, Marjorie, and Maurice—were staying in Aunt Julia’s house. It was a lonely old house, much too big for that one wicked old lady; it stood outside a North Yorkshire village, just where a grand, dignified old hill drew back its skirts, with a sharp sweep, from contamination with human dwelling-places. Aunt Julia owned quarries at the foot of the hill, and got therefrom more money than was good for her. The time was December, and the moors looked bleak and cold. But it was a comfortable house. Aunt Julia had devoted her many years to the study of comfort—her own comfort. “There is nothing to shoot,” she explained to Maurice, “except my tenants down in the village. You can shoot them, if you like. There’s the library, though, which is good, and you can smoke anywhere you like——”

“But you used to hate smoking?” said Maurice.

“My dear Maurice, there are two of me, and you used to know the wrong one. Down in the village they mostly know the wrong one, and they call her, I am told, the hell-cat, which is rude of them. Yes, you can smoke anywhere. If you and Marjorie want to go out of the house—which is a thing I never do in December—I believe there are some horses round at the back. If there is anything wrong about the horses, or Pilkin, or anything that is his, just tell me, and I will say a word or two. I believe the man presumes on my ignorance. You can go and see my quarries, or my cottages; but you had better not go to the cottages, because they have no drains. I should like to give them some drains, but the tenants won’t let me. They are poor people, and a strong smell makes a difference to their colourless existence.”

So Maurice did a certain amount of reading, riding, and smoking. But, of course, Marjorie made for him the chief charm of the house. Mrs. Meyner had willingly consented to the engagement; even if she had desired to oppose it, her more strenuous half-sister would have reasoned her out of it; or, to use her own gentle euphemism, would have said a word or two. The days passed quietly enough. To Maurice they were a pleasant rest after his three years of wasted laboriousness. “Marjorie,” he said to her one afternoon, when they had wandered over the dignified hill, and as they came back saw the bare boughs of the trees in the plantation black against a red blot of sunset, “Marjorie, I have done with all questions. I am here, and you are here, and that is enough for me. I am going to live and love, and enjoy. Blessed be my fate that has saved me from the sordid worry of life. (Just wait a second, will you? can’t get a match to light in this wind.) We will make a beautiful house, with beautiful things in it, with good books on shelves, and good wine in the cellar, and a good cook in the kitchen. And no one shall enter into that house who is not either very beautiful, or very clever, or too good for this world.”

“But I shall be so lonely there without you,” said Marjorie, gently, with her sparkling eyes looking groundwards.

Maurice laughed. “Ah, Marjorie, you and I will be one, and you are more beautiful, and clever, and better than any one in the world. That is how I shall have a right to come into my own beautiful house. We will trouble ourselves with no theories about anything. We will not get excited about anything; an excited man always has been, or will be, dull. We will make life one long, gentle enjoyment.”

He spoke half in jest and half in earnest, telling his soul of beautiful things laid up in that house for many years; bidding himself to eat, and drink, and enjoy judiciously.

Perhaps it was because Marjorie at that moment looked towards the sunset. It seemed so far away from her, and yet so desirable. She had the fancy, common among children and poets, that the dying light looked the gate of some wonderful place to be seen hereafter.

“Maurice, Maurice!” she cried. “Look at that. I have the lost, prisoned feeling again when I look at it. It is too far away.”

That night ended all. There were beautiful things to come, so it seemed to both of them, such poetry and love as never had been before; and all was stopped by an accident, one commonplace accident, almost too poor to be put into a story.

Marjorie had been subdued, almost depressed; she had talked but little at dinner or afterwards. Mrs. Meyner and Marjorie both went to bed rather early. Maurice, restless from his love-passion, had gone to walk and smoke for an hour on the fell-side. Aunt Julia sat before the fire in the drawing-room, waiting for Maurice to return, reading a favourite chapter of Gibbon.

For some time one would have said that Marjorie was sleeping quietly and peacefully. Then suddenly she sat up in bed, her eyes still closed. She began talking in her sleep. “Tell me! Come back again and tell me. I will know. I am on the verge, and—and——.” She stopped talking; quickly she moved from the bed to the dressing-table, and her fingers fumbled impatiently with the opening of her dressing-case. She had drawn up the blind, and the moonlight shone straight upon her. Her lips were still moving, but no sound came. She opened the dressing-case and took from it a glass jar which was filled with old dead rose leaves. She had filled it herself long before, when she was a child. She unscrewed the silver top, and began to take out the rose leaves very carefully. At the bottom of the jar she found the thing for which she had been looking, and laid it on the palm of her little white hand. It was the withered body of a large dead beetle.

For a moment she stood thus. And then she drew a long breath, and opened her eyes wide. She was awake, and she had remembered the horrible thing which she had heard in a dream and had forgotten. Quivering and almost breathless she hurried from the room, just as she was.

Aunt Julia had good nerves, but she was a little startled when the door of the drawing-room was flung open, and she saw, standing in the doorway, the figure of Marjorie, white-robed, bare-footed, with both hands stretched out, and struggling in vain, as it seemed, to speak.

“Marjorie! What is it?” cried Aunt Julia in a shaking voice.

She found words at last.

“Maurice is dead—dead! He fell—I saw him fall—over there, against the plantation, down into the quarry. He is dead!”