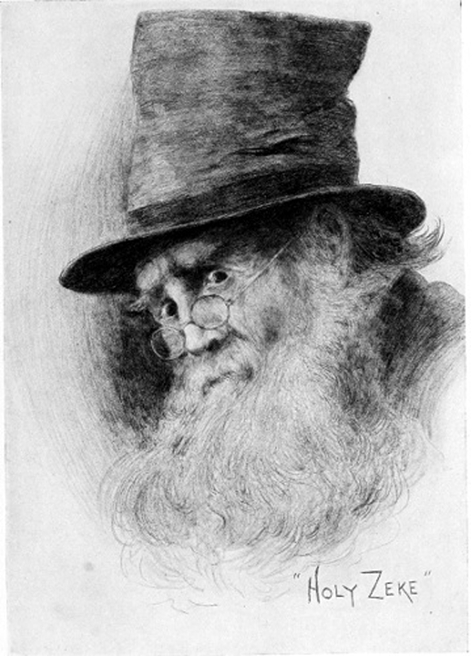

HOLY ZEKE

By Earl Howell Reed

“And mine eye shall not spare, neither will I have pity; I will recompense thee according to thy ways and thine abominations that are in the midst of thee; and ye shall know that I am the Lord that smiteth.”—Ezekiel 7:9

AFTER an industrious day with my sketch book among the dunes, I walked over to the lake shore and looked up the beach toward Sipes’s shanty. In the gathering twilight a faint gleam came through the small window. Not having seen my old friend for nearly a year, I decided to pay him a visit. My acquaintance with him had brought me many happy hours as I listened to his reminiscences, some of which are recorded in former stories.

He had been a salt water sailor, and, with his shipmate Bill Saunders, had met with many thrilling adventures. He had finally drifted to the sand-hills, where he had found a quiet refuge after a stormy life. Fishing and hunting small game yielded him a scanty but comparatively happy livelihood. He was a queer, bewhiskered little man, somewhere in the seventies, with many idiosyncrasies, a fund of unconscious humor, much profanity, a great deal of homely philosophy, and with many ideas that were peculiarly his own.

He wore what he called a “hatch” over the place which his right eye formerly occupied, and explained the absence of the eye by telling me that it had been blown out in a gale somewhere off the coast of Japan. He said that “it was glass anyway” and he “never thought much of it.” Saunders figured more or less in all of his stories of the sea.

On approaching the nondescript driftwood structure, I heard a stentorian voice, the tones of which the little shanty was too frail to confine, and which seemed to be pitched for the solemn pines that fringed the brink of the dark ravine beyond.

“Now all ye hell-destined sinners that are in this holy edifice, listen to me! Ye who are steeped in sin shall frizzle in the fires o’ damnation. The seethin’ cauldrons yawn. Ye have deserved the fiery pit an’ yer already sentenced to it. Hell is gaping fer this whole outfit. The flames gather an’ flash. The fury o’ the wrath to come is almost ’ere. Yer souls are damned an’ you may all be in hell ’fore tomorrer mornin’. The red clouds o’ comin’ vengeance are over yer miserable heads. You’ll be enveloped in fiery floods fer all eternity—fer millions of ages will ye sizzle. Ye hang by a slender thread. The flames may singe it any minute an’ in ye go. Ye have reason to wonder that yer not already in hell! Yer accursed bodies shall be laid on live coals, an’ with red-hot pitch-forks shall ye be sorted into writhin’ piles an’ hurled into bottomless pits of endless torment. I’m the scourge o’ the Almighty. I’m Ezekiel-seven-nine. This is yer last chance to quit, an’ you’ve got to git in line, an’ do it quick if ye want to keep from bein’ soused in torrents o’ burnin’ brimstone, an’ have melted metal poured into yer blasphemous throats!”

At this point the door partially opened and a furtive figure slipped out. “Let all them that has hard hearts an’ soft heads git out!” roared the voice. The figure moved swiftly toward me and I recognized Sipes.

“Gosh! Is that you? You keep away from that place,” he sputtered, as he came up.

“What seems to be the trouble?” I asked.

“It’s Holy Zeke an’ he’s cussin’ the bunch. It looks like we’d all have a gloomy finish. He was up ’ere this mornin’ an’ ast me if ’e could ’ave a reevival in my place tonight. He’s ’ad pretty much ev’rythin’ else that was loose ’round ’ere, an’ like a damn fool I told ’im O. K., an’ this is wot I git. I thought it was sump’n else. You c’n go an’ listen to ’is roar if you want to, but I got some business to ’tend to ’bout ten miles from ’ere, an’ I wont be back ’till tomorrer, an’ w’en I come back it’ll be by water. I’m goin’ to lay fer that ol’ skeet with my scatter gun, an’ he’ll think he’s got hot cinders under ’is skin w’en I git to ’im. I’ll give ’im all the hell I can without murderin’ ’im.” Sipes then disappeared into the gloom, muttering to himself.

His “scatter gun” was a sinister weapon. It had once been a smooth-bore army musket. The barrel had been sawed off to within a foot of the breach. It was kept loaded with about six ounces of black powder, and, wadded on top of this, was a handful of pellets which the old man had made of flour dough, mixed with red pepper, and hardened in the sun. He claimed that, at three rods, such a charge would go just under the skin. “It wouldn’t kill nothin’, but it ’ud be hot stuff.”

I sat on a pile of driftwood for some time and waited for the turmoil in the shanty to subside. Finally the door opened and four more figures emerged. I was glad to recognize my old friend “Happy Cal,” whom I had not seen since his mysterious departure from the sand-hills several years ago, after his dispute with Sipes over some tangled set-lines. Evidently the two old derelicts had amicably adjusted their differences, and Cal had rejoined the widely scattered colony. Another old acquaintance, “Catfish John,” was also in the party. After greetings were exchanged, John introduced me to a short stocky man with gray whiskers.

“Shake hands with Bill Saunders,” said he.

This I did with pleasure, as Sipes’s yarns of the many exploits of this supposedly mythical individual invested him with much interest.

“This ’ere’s Ezekiel-seven-nine,” continued John, indicating the remaining member of the quartette.

I offered “Ezekiel-seven-nine” my hand, but it was ignored. He looked at me sternly. “Yer smokin’ a vile an’ filthy weed,” said he. “It defiles yer soul an’ yer body. It’s an abomination in the sight o’ the Lord. Yer unclean to my touch.” With that he turned away.

I glanced at his hands and if anything could be “unclean” to them its condition must be quite serious. I quite agreed with him, but from a different standpoint, that the cigar was “an abomination,” and, after a few more doubtful whiffs, I threw it away, as I had been tempted to do several times after lighting it. Its purchase had proved an error of judgment.

Zeke’s impressions of me were evidently not very favorable. He walked away a short distance and stopped. In the dim light I could see that he was regarding us with disapproval. He took no part in the conversation. He finally seated himself on the sand and gazed moodily toward the lake for some time, probably reflecting upon the unutterable depravity of his present associates, and calculating their proximity to eternal fire.

“Holy Zeke,” as Sipes had called him, was about six feet two. His clothes indicated that they had been worn uninterruptedly for a long time. The mass of bushy red whiskers would have offered a tempting refuge for wild mice, and from under his shaggy brows the piercing eyes glowed with fanatic light.

Calvinism had placed its dark and heavy seal upon his soul, and the image of an angry and pitiless Creator enthralled his mind—a God who paves infernal regions with tender infants who neglect theology, who marks the fall of a sparrow, but sends war, pestilence and famine to annihilate the meek and pure in heart.

The wonderful drama of the creation, and the beautiful story of Omnipotent love carried no message for him. Lakes of brimstone and fire awaited all of earth’s blindly groping children who failed to find the creed of the self-elect. Notwithstanding the fact that the national governing board of an orthodox church, with plenary powers, convened a few years ago, officially abolished infant damnation, and exonerated and redeemed all infants, who up to that time had been subjected to the fury of Divine wrath, Zeke’s doctrine was unaltered. It glowed with undiminished fervor. He was a restless exponent of a vicious and cruel man-made dogma, which was as evil as the punishments it prescribed, and as futile as the rewards it promised.

To me Holy Zeke was an incarnation. His eyes and whiskers bespoke the flames of his theology, and his personality was suggestive of its place in modern thought. His battered plug hat was also Calvinistic. It looked like hades. It was indescribable. One edge of the rim had been scorched, and a rent in the side of the crown suggested the possibility of the escape of volcanic thought in that direction. Like his theology, he had picturesque quality.

If he had been a Mohammedan, his eyes would have had the same gleam, and he would have called the faithful to prayer from a minaret with the same fierce fervor as that with which he conjured up the eternal fires in Sipes’s shanty. Had not Calvinism obsessed him, his type of mind might have made him a murderous criminal and outlaw, who, with submarines and poison gas, would deny mercy to mankind, for there was no quality of mercy in those cruel orbs. They were the baleful eyes of the jungle, that coldly regard the chances of the kill. In Holy Zeke’s case the kill was the forcible snatching of the quarry from hell, not that he desired its salvation, but was anxious to deprive the devil of it. He had no idea of pointing a way to righteousness. There was no spiritual interest in the individual to be rescued. He was the devil’s implacable enemy, and it was purely a matter of successful attack upon the property of his foe. Predestination or preordination did not bother him. He made no distinctions. There was no escape for any human being whose belief differed from his; even the slightest variation from his infallible creed meant the bottomless pit.

Zeke had one redeeming quality. He was not a mercenary. No board of trustees paid him the wages of hypocrisy. He did not arch his brows and fingers and deliver carefully prepared eloquent addresses to the Creator, designed more for the ears of his listeners than for the throne above. He did not beseech the Almighty for private favors, or for money to pay a church debt. He regarded himself as a messenger of wrath, and considered that he was authorized to go forth and smite and curse anything and everything within his radius of action. This radius was restricted to the old derelicts who lived in the little driftwood shanties along the beach and among the sand-hills. There were but few of them, but the limited scope of Zeke’s labors enabled him to concentrate his power instead of diffusing and losing it in larger fields.

Zeke soon left our little party and followed a path up into the ravine. After his departure we built a fire of driftwood, sat around it on the sand, and discussed the “scourge.”

“I hate to see anythin’ that looks like a fire, after wot we’ve been up ag’inst tonight,” remarked Cal, as he threw on some more sticks, “but as ’e ain’t ’ere to chuck us in, I guess we’ll be safe if we don’t put on too much wood. Where d’ye s’pose ’e gits all that dope? I had a Bible once’t, but I didn’t see nothin’ like that in it. There was a place in it where some fellers got throwed in a fiery furnace an’ nothin’ happened to ’em at all, an’ there was another place where it said that the wicked ’ud have their part in hell fire, but I didn’t read all o’ the book an’ mebbe there’s a lot o’ hot stuff in it I missed. W’en did you fust see that ol’ cuss, John?”

Catfish John contemplated the fire for a while, shifted his quid of “natural leaf,” and relighted his pipe. He always said that he “couldn’t git no enjoyment out o’ tobacco without usin’ it both ways.”

“He come ’long by my place one day ’bout three years ago,” said the old man. “It was Sunday an’ ’e stopped an’ read some verses out of ’is Bible while I was workin’ on my boat. He said the Lord rested on the seventh day, an’ I’d go to hell if I didn’t stop work on the Sabbath. I told ’im that my boat would go to hell if I didn’t fix it, an’ they wasn’t no other day to do it. Then ’e gave me wot ’e called ‘tracks’ fer me to read an’ went on. The Almighty’s got some funny fellers workin’ fer ’im. This one’s got hell on the brain an’ ’e ought to stay out in the lake where it’s cool. Ev’ry little while ’e comes ’round an’ talks ’bout loaves an’ fishes, an’ sometimes I give ’im a fish, w’en I have a lot of ’em. He does the loaf part ’imself, fer sometimes ’e sticks ’round fer an hour or two. Then ’e tells me some more ’bout hell an’ goes off some’r’s, prob’ly to cook ’is fish.”

“Sipes must ’a’ come back. Let’s go over there,” suggested Saunders, as he called our attention to the glimmer of a light in the shanty.

As we approached the place the light was extinguished, and a voice called out, “Who’s there?”

After the identity of the party had been established, and the assurance given that Holy Zeke was not in it, the light reappeared and we were hospitably received.

“Wot did you fellers do with that hell-fire cuss?” demanded Sipes when we were all seated in the shanty. “Look wot’s ’ere!” and he picked up a small, greasy hymn book which the orator had forgotten in the excitement. Sipes handed me the book. I opened it at random and read:

“Not all the blood of beasts, on Jewish altars slain,

Can give the guilty conscience peace, or wash away the stain.”

“Gimme that!” yelled Sipes, and I heard the little volume strike the sand somewhere out in the dark near the water. “Wot d’ye s’pose I got this place fer if it ain’t to have peace an’ quiet ’ere, an’ wot’s this red-headed devil comin’ ’round ’ere fer an’ fussin’ me all up tell’n’ me where I’m goin’ w’en I die, w’en I don’t give a whoop where I go when I die. That feller’s bunk an’ don’t you fergit it, an’ ’e’s worse’n that, fer look ’ere wot I found in that basket where I had about two pounds o’ salt pork!”

He produced a piece of soiled and crumpled paper, on which were scrawled the following quotations: “Of their flesh shall ye not eat, and their carcass shall ye not touch. They are unclean to you” (Leviticus 11:8). “Curséd shall be thy basket and thy store” (Deuteronomy 28:17).

“It’s all right fer ’im to cuss my basket if ’e wants to, but I ain’t got no store. I’ll bet ’e frisked that hunk o’ pork an’ chucked in them texts ’fore you fellers got ’ere an’ I got in off’n the lake. It was in ’is big coat pocket all the time he was makin’ that hot spiel, an’ that’s w’y ’e didn’t ’ave no room fer ’is hymn book. He’s swiped my food an’ I can’t fry them texts, an’ you fellers are all in on it fer I was goin’ to cook the pork an’ we’d all have sump’n to eat. He cert’nly spread hell ’round ’ere thick tonight. Some day he’ll be yellin’ fer ice all right. Who are them Leviticus an’ Deuteronomy fellers anyhow? They ain’t no friends o’ mine!

“I’m weary o’ that name o’ Zekiel-seven-nine he’s carryin’ ’round. ’E ought to have an eight spot in it, an’ with a six an’ a ten ’e’d ’ave a straight an’ it ’ud take a flush er a full house to beat ’im. I bet ’e’s a poker sharp, an’ ’e’s hidin’ from sump’n over ’ere, an’ ’e ain’t the fust one that’s done it. I seen ’im stewed once’t an’ ’e had a lovely still. He’d oozed in the juice over to the county seat an’ come over ’ere an’ felt bad about it in my shanty. He come up to the window w’en I was fixin’ my pipe an yelled, ‘Bow ye not down ’afore idols!’ I went out an’ hustled ’im in out o’ the wet. It was rainin’ pretty bad an’ ’e was soaked, but ’e said ’e didn’t care so long’s none of it didn’t git in ’is stummick. I dassent light a match near ’is breath.

“I had ’im ’ere two days, an’ ’e said he’d took sump’n by mistake, an’ ’e had. I had to keep givin’ ’im more air all the time. He drunk enough water the next mornin’ to put out a big fire an’ I guess ’e had one in ’im all right. After that ’e ast me if I had any whiskey, an’ w’en I told ’im I didn’t, ’e said ’e was glad of it, fer it was devil’s lure. He’d ’a’ stowed it if he’d got to it. I did ’ave a little an’ I guess now’s a good time to git it out, an’ I hope I don’t find no texts stuck in the jug. We all need bracin’ up, so ’ere goes! That feller’s a blankety-blankety-blank—blank-blank, an’ besides that ’e’s got other faults!”

It seems a pity to have to expurgate Sipes’s original and ornate profanity from his discourses, but common decency requires it. The old man left the shanty with a lantern and shovel. A few minutes later we saw his light at the edge of the lake where he was washing the sand from the outside of his jug. Evidently it had been buried treasure.

“I’ve et an’ drunk so much sand since I been livin’ ’ere on this beach that my throat’s all wore out an’ full o’ little holes, an’ I ain’t goin’ to swaller no more’n I c’n help after this,” he remarked, as he came in and hung the lantern on its hook in the ceiling; “now you fellers drink hearty.”

At this juncture a wailing sepulchral voice, loud and deep, came out of the darkness in the distance.

“Beware! Beware! Beware! In the earth have ye found damnation!”

“There ’e is!” yelled Sipes, as he leaped across the floor for his scatter-gun. He ran out with it and was gone for some time. He returned with an expression of disgust on his weather-beaten face. “I’ll wing that cuss some night ’fore the snow falls,” he remarked, as he resumed his seat. “We’d better soak up all this booze tonight fer it won’t be safe in any o’ the ground ’round ’ere any more. Gosh! but this is a fine country to live in!”

The party broke up quite late. Happy Cal had imbibed rather freely. Catfish John had been more temperate, and thought he had “better go ’long with Cal,” and it seemed better that he should. As they went away I could hear Cal entertaining John with snatches of some old air about “wine, women, an’ song.” They stopped a while at the margin of the lake, where the wet sand made the walking better, and Cal affectionately assured John of his eternal devotion. They then disappeared.

I bade Sipes and his old shipmate good-night, and left them alone with the demon in the jug. There was very little chance of any of it ever falling into the hands of “the scourge,” who was evidently lurking in the vicinity.

The glory of the full moon over the lake caused Sipes to remark that “ev’rythin’s full tonight,” as he followed me out to bid me another good-by. After I left I could hear noisy vocalism in the shanty. The words, which were sung over and over, were:

“Comrades, comrades, ever since we was boys,—

Sharing each other’s sorrows, sharing each other’s joys.”

After each repetition there would be boisterous, rhythmic pounding of heavy boots on the wooden floor.

While the song was in many keys, and was technically open to much criticism, it was evidently sincere. The old shipmates were happy, and, after all, besides happiness, how much is there in the world really worth striving for?

I walked along the beach for a couple of miles to my temporary quarters in the dunes, and the stirring events of the evening furnished much food for reflection. I was interested in the advent of Bill Saunders, concerning whom I had heard so much from Sipes. Bill was a good deal of a mystery. He had “showed up” a few days before in response to a letter which Sipes told me he had “put in pustoffice fer ’im.” He may at some time have lived on the “unknown island in the South Pacific” that Sipes told me about, where he and Bill had been wrecked, and Bill had “married into the royal family several times,” but evidently he had deserted his black and tan household. For at least two years he had been living over on the river. Sipes explained that he stayed there “so as to be unbeknown.” For some reason which I did not learn, he and Sipes considered it advisable for him to “keep dark” for a while. The trouble, whatever it was, had evidently blown over, and Bill had returned to the sand-hills.

There was a rudely painted sign on the shanty a few days later, which read:

$IPE$ & $AUNDER$—FRE$H FI$H

“It might ’a’ been Saunders & Sipes,” said the old man to me, confidentially, “but I think Sipes & Saunders sounds more dignified like, don’t you? We got ‘fresh fish’ on the sign so’s people won’t git ’em mixed up with the kind o’ fish John peddles. Them fish are fresh w’en John gits ’em ’ere, but after ’e’s ’ad ’em ’round a while there’s invisible bein’s gits into ’em out o’ the air, an’ you c’n smell ’em a mile. W’en they git to be candydates fer ’is smoke-house their ol’ friends wouldn’t know ’em, an’ I put them up an’ down lines in them S’s in them names so’s to make the sign look like cash money.”

Several days later I discovered that my tent had been visited during my absence. Outside, pinned to the flap, was a piece of paper on which was written:

“All ye who smoke or chew the filthy weed shall be damned.”

“The breath of hell, an angry breath,

Supplies and fans the fire,

When smokers taste the second death

And shriek and howl, but can’t expire.”

Inside, on the cot, were several tracts containing extracts from sermons on hell by an old ranter of early New England days, setting forth the practical impossibility of anybody ever escaping it.

I examined the literature with interest and amusement. Some of the more virulent paragraphs were marked for my benefit.

I looked out over the landscape, with its glorious autumn coloring, to the expanse of turquoise waters beyond, and wondered if, above the fleecy clouds and the infinite blue of the heavens, there was an Omnipotent monstrosity Who gloried in the torture of what He created, and brought forth life that He might wreak vengeance upon it. Ignorance, fear, and superstition have led men into strange paths. It may be that our philosophy will finally lead us back to the beginning, and teach us that we are humble, wondering children who do not understand, and that there is a border land beyond which we may not go.

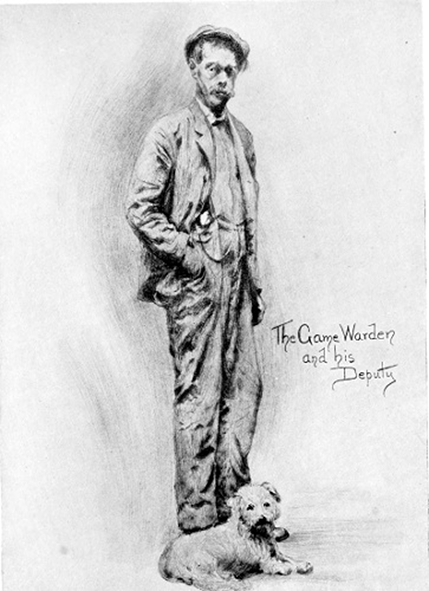

I met the firm of Sipes & Saunders on the beach one morning, on their way to Catfish John’s place, which was about four miles from their shanty. John’s abode was on a low bluff, and on the beach near it, about a hundred feet from the lake, was the little structure in which he smoked what Sipes called “them much-deceased fish” which he had failed to sell. His peddling trips were made through the back country with a queer little wagon and a rheumatic horse, that bore the name of “Napoleon” with his other troubles. Some of the fish were from his own nets, but most of his supplies were obtained from Sipes on a consignment basis.

At the earnest solicitation of the old mariners, I turned back and went with them to call on John. Sipes said that I “had better come along fer there’s goin’ to be sump’n doin’.”

We found the old man out on the sand repairing his gill-nets.

“Wot ’ave I done that I should be descended on like this?” he asked jocularly, as we came up. “You fellers must be lookin’ fer trouble, fer Zeke’s comin’ ’ere this mornin’ fer a fish that I told ’im ’e could ’ave if I got any.

“I figgered it all out,” said Sipes, “cause Bill heard you tell ’im you was goin’ to lift the nets Sunday, an’ I seen you out’n the lake with the spotter, an’ as Bill an’ me’s got some business with Zeke, we thought we’d drop ’round.”

Sipes’s “spotter” was an old spy glass, which he declared “had been on salt water.” Through a small hole in the side of his shanty he could sweep the curving shore for several miles with the rickety instrument.

I walked over to the smoke-house with the party and inspected it with much interest. The smoke supply came from a dilapidated old stove on the sand from which a rusty pipe entered the side of the structure. The smoke escaped slowly through various cracks in the roof, which provided a light draft for the fire.

“That smoke gits a lot of experience in this place ’fore it goes out through them cracks,” remarked Sipes, as he opened the door and peered inside. “I don’t blame it fer leavin’. Can ye lock this door tight, John?”

I curiously awaited further developments.

It was not long before we saw Zeke plodding toward us on the sand.

“Now don’t you fellers say nothin’. You jest set ’round careless like, an’ let me do the talkin’,” cautioned Sipes, as he filled his pipe. With an expressive closing of his single eye, he turned to me confidentially and said with a chuckle, “We’re goin’ to fumigate Zeke.”

There was a look of quiet determination in his face, and guile in his smile as he contemplated the approaching visitor.

“Hello, Zeke!” he called out, as soon as that frowsy individual was within hailing distance, “wot’s the news from hell this fine mornin’?”

We smiled at Sipes’s sally. Zeke looked at us solemnly, and in deep impressive tones replied: “Verily, them that laughs at sin, laughs w’en their Maker frowns, laughs with the sword o’ vengeance over their heads.”

“Oh, come on, Zeke, cut that out,” said Sipes, “an’ let’s go in an’ see the big sturgeon wot John got this mornin’. It’s ’ere in the smoke-house.” Sipes led the way to the door and opened it. Zeke peeked in cautiously.

“It’s over in that big box with them other fish near the wall,” said Sipes. Zeke stepped inside. Sipes instantly closed the door and sprung the padlock that secured it. He then ran around to the stove and lighted the fuel with which it was stuffed.

An angry roar came from the interior, as we departed. After we reached the damp sand on the shore, Sipes joyfully exclaimed, “Verily we’ll now ’ave to git a new scourge, fer this one’s up ag’inst damnation!”

While John had passively acquiesced in the proceedings, I knew that he did not intend to allow Sipes’s escapade to go too far, so I did not worry about Zeke.

As we walked down the shore, Sipes and Bill turned frequently to look at the softly ascending wreaths from the roof with much glee.

“That coop’s never ’ad nothin’ wuss in it than it’s got now,” declared Sipes. “That ol’ bunch o’ whiskers ’as got wot’s comin’ to ’im this time, an’ I wish I’d stuck John’s rubber boots in that stove, but, honest, I fergot it.”

We had gone quite a distance when I turned and discerned a retreating form far beyond the smoke-house close to the bluff. One side of the structure was wrecked, and it was evident that the “scourge” had broken through and escaped. I said nothing, as I did not want to mar the pleasure of the old shipmates. To them it was “the end of a perfect day.”

A little further on I left them and turned into the dunes. As they waved farewell, Sipes called out cheerily, “You c’n travel anywheres ’round ’ere now without git’n’ burnt!”

Later, from far away over the sands, I could faintly hear:

“Shipmates, shipmates, ever since we was boys—

Sharing each other’s sorrows, sharing each other’s joys!”

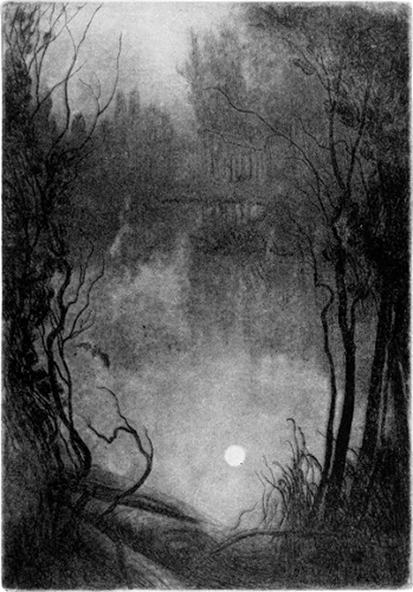

One night I encased myself in storm-defying raiment and went down to the shore to contemplate a drama that was being enacted in the skies.

Swiftly moving battalions of stygian clouds were illuminated by almost continuous flashes of lightning. Heavy peals of thunder rolled through the convoluted masses, and reverberated along the horizon. The wind-driven rain came in thin sheets that mingled with the flying spray from the waves that swept the beach. The sublimity of the storm was soul stirring and inspiring. I plodded for half a mile or so along the surf-washed sand to the foot of a bluff on which were a few old pines, to see the effect of the gnarled branches against the lightning-charged clouds.

A brilliant flash revealed a silhouetted figure with gesticulating arms. It was Holy Zeke. His battered plug was jammed down over the back of his head, and his long coat tails were flapping in the gale. The apparition was grotesque and startling, but seemed naturally to take its place in the wild pageant of the elements. It added a note of human interest that seemed strangely harmonious.

I did not wish to intrude on him, or allow him to interfere with my enjoyment of the storm, but passed near enough to hear his resonant voice above the roar of the wind.

He was in his element. He had sought a height from which he could behold the scourging of the earth, and pour forth imprecations on imaginary multitudes of heretics and unbelievers. With fanatic fervor he was calling down curses upon a world of hopeless sin. Hatred of human kind was exhaled from his poisoned soul amid the fury of the storm.

To his disordered imagination, any unusual manifestation of nature’s forces was an expression of Divine wrath. Condemnation was now coming out of the black vault above him, and the vengeance of an incensed Diety was being heralded from on high. Unregenerate sinners and rejectors of Zeke’s creed were in the hands of an angry God. The scroll of earth’s infamy was being unrolled out of the clouds. “The seventh vial” was being poured out, and the hour of final damnation was at hand.

In the armor of his infallible orthodoxy, like Ajax, he stood unafraid before the lurid shafts. Serene in his exclusive holiness he was immune from the fiery pit and the shambles of the damned, and gloried in the coming destruction of all those unblessed with his faultless dogma.

The storm was increasing in violence, and I had started to return. After going some distance I turned for a final view of Zeke, and it was unexpectedly dramatic.

There was a sudden dazzling glare, and a deafening crash. A tall tree, not far from where he stood, was shattered into fragments. The shock was terrific. He was gone when a succeeding flash lighted the scene. Fearing that the old man might have met fatality, or at least have been badly injured, I hurried back and climbed the steep path that led to the top of the promontory from the ravine beyond it. Careful search, with the aid of an electric pocket light and the lightning flashes, failed to reveal any traces of the old fanatic, and it was safe to assume that he had retreated in good order from surroundings that he had reluctantly decided were untenable.

The bolt that struck the tree was charged with an obvious moral that was probably lost on the fugitive.

The old shipmates were much interested when they heard the tale of the night’s adventure.

“That ol’ cuss’ll git his, sometime, good an’ plenty,” observed Sipes. “Sump’n took a pot shot at Zeke an’ made a bad score. It would ’a’ helped some if the lightnin’ ’ad only got that ol’ hat o’ his. Prob’ly it’s been hit before. Zeke ’ad better look out. He’s been talkin’ too much ’bout them things. It’s too bad fer a nice tree like that to git all busted up. No feller with a two-gallon hat an’ red whiskers ever oughta buzz ’round in a thunder storm.”

John was quite philosophical about Zeke.

“He ought to learn to stay in w’en it’s wet. His kind o’ relig’n don’t mix with water, an’ some night ’e’ll go out in a storm like that an’ ’e won’t come back. He was ’round ’ere this mornin’ tell’n me ’bout the signs o’ the times an’ heav’nly fires.

“Them ol’ fellers hadn’t ought to fuss so much ’bout ’im. They come up ’ere the day after they smoked ’im, an’ fixed my smoke-house all up fer me. They said thar was too many cracks ’round in it, an’ the boards ’round the sides was all too thin. They got some heavy boards an’ big nails an’ they done a good job. They said they’d fixed it so it ’ud hold a grizzly b’ar if I wanted to keep one, an’ I was glad they come up.

“When Zeke broke through ’e didn’t fergit ’is fish. He took the biggest one thar was in the box. When ’e went off ’e was yell’n sump’n ’bout them that stoned an’ mocked the prophets, an’ sump’n ’bout a feller named Elijah, that was goin’ up in a big wind in a chair o’ fire, but I didn’t hear all of it, fer ’e was excited. Zeke’s a poor ol’ feller. It’s all right fer ’em to cuss ’im, fer ’e gives it to ’em pretty hard w’en ’e gits down thar, but that don’t do no harm. They ain’t no nearer hell than they’d be without Zeke tell’n ’em ’bout it all the time. He’s part o’ the people what’s ’round us, an’ we ought to git ’long with ’im. I’ll alw’ys give ’im a fish when ’e’s hungry, even if ’e does think I’m goin’ to hell.”