THE HERON’S POOL

By Earl Howell Reed

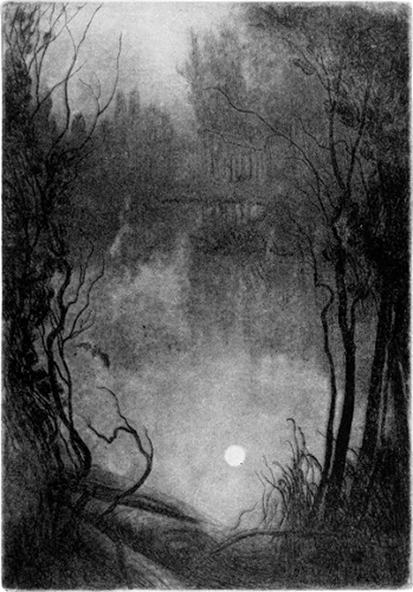

THE HERON’S POOL(From the Author’s Etching)

THE pool was far back from the big marshes through which the lazy current of the river wound. It was in one of those secluded nooks that the seeping water finds for itself when it would hide in secret retreats and form a little world of its own. It was bordered by slushy grasses and small willows; its waters spread silently among the bulrushes, lily pads and thick brush tangles. A few ghostly sycamores and poplars protruded above the undergrowth, and the intricate network of wild grape-vines concealed broken stumps that were mantled with moss. The placid pool was seldom ruffled, for the dense vegetation protected it from the winds. Wandering clouds were mirrored in its limpid depths. Water-snakes made silvery trails across it. Sinister shadows of hawks’ wings sometimes swept by, and often the splash of a frog sent little rings out over the surface. Opalescent dragon-flies hovered among the weeds and small turtles basked in the sun-light along the margins.

The Voices of the Little Things were in this abode of tranquillity—the gentle sounds that fill nature’s sanctuaries with soft music. There were contented songs of feathered visitors, distant cries of crows beyond the tree-tops, faint echoes of a cardinal, rejoicing in the deep woods, and the drowsy hum of insects—the myriad little tribes that sing in the unseen aisles of the grasses.

One spring a gray old heron winged his way slowly over the pool, and, after a few uncertain turns over the trees, wearily settled among the rushes. After stalking about in the labyrinth of weeds along the shallow edges for some time, he took his station on a dead branch that protruded from the water near the shore, and solemnly contemplated his surroundings.

His plumage was tattered, and he bore the record of the years he had spent on the marshy wastes along the river. His eye had lost its lustre, and the delicate blue that had adorned the wings of his youth had faded to a pale ashen gray. The tired pinions were slightly frayed—the wings hung rather loosely in repose, and the lanky legs carried scars and crusty gray scales that told of vicissitudes in the battle for existence. He looked long and curiously at a round white object on the bottom near his low perch. The round object had a history, but its story did not come within the sphere of the heron’s interests, and he returned to his meditations on the gnarled limb. He may have dreamed of far-off shores and happy homes in distant tree-tops. A memory of a mate that flew devotedly by his side, but could not go all the way, may have abided with him. The peace of windless waters brooded in this quiet haven. It was a refuge from the storms and antagonisms of the outer world, its store of food was abundant, and in it he was content to pass his remaining days.

When night came his still figure melted into the darkness. A fallen luna moth, whose wet wings might faintly reflect the starlight, would sometimes tempt him, and he would listen languidly to the lonely cries of an owl that lived in one of the sycamores. The periodic visits of coons and foxes, that prowled stealthily in the deep shadows, and craftily searched the wet grasses for small prey, did not disturb him. They well knew the power of the gray old warrior’s cruel bill. All his dangerous enemies were far away. The will-o’-the-wisps that spookily and fitfully hovered along the tops of the rushes, and the erratic flights of the fire-flies, did not mar his serenity. He was spending his old age in comfort and repose.

There is a certain air, or quality, about certain spots which is indefinable. An elusive and intangible impression, an idea, or a story, may become inseparably associated with a particular place. With a recurrence of the thought, or the memory of the story there always comes the involuntary mental picture of the physical environment with which it is interwoven. This association of thought and place is in most cases entirely individual, and is often a subtle sub-consciousness—more of a relationship of the soul, than the mind, to such an environment. Something in or near some particular spot that imparts a peculiar and distinctive character to it, or inspires some dominant thought or emotion, constitutes the “genius” of that place. The Genius of the Place may be a legend, an unwritten romance, a memory of some event, an imaginary apparition, an unaccountable sound, the presence of certain flowers or odors, a deformed tree, a strange inhabitant, or any thought or thing that would always bring it to the mind.

When the heron came to the pool the Genius of the Place was old Topago, a chief of the Pottawattomies. A great many years ago he lived in a little hut, rudely built of logs and elm bark, on an open space a few hundred feet from the pool. The fortunes of his tribe had steadily declined, and their sun was setting. After the coming of the white man, war and sickness had decimated his people. The wild game began to disappear and hunger stalked among the little villages. The old chief brooded constantly over the sorrows of his race. As the years rolled on his melancholy deepened. He sought isolation in the deep woods and built his lonely dwelling near the pool to pass his last years in solitude. His was the anguish of heart that comes when hope has fled. Occasionally one of the few faithful followers who were left would come to the little cabin and leave supplies of corn and dried meat, but beyond this he had no visitors. His contact with his tribe had ceased.

One stormy night, when the north wind howled around the frail abode, and the spirits of the cold were sighing in the trunks of the big trees, the aged Indian sat over his small fire and held his medicine bag in his shrivelled hands. Its potent charm had carried him safely through many perils, and he now asked of it the redemption of his people. That night the wind ceased and he felt the presence of his good manitous in the darkness. They told him that the magic of his medicine was still strong. If he would watch the reflections in the pool, there would sometime appear among them the form of a crescent moon that would foretell a great change in the fortunes of his race, but he must see the reflection with his own eyes.

In the spring, as soon as the ice had melted, he began his nightly vigils at the foot of an ancient pine that overhung the water. Through weary years he gazed with dimmed eyes upon the infinite and inscrutable lights that gleamed and trembled in the pool. Many times he saw the new moon shine in the twilights of the west, and saw the old crescent near the horizon before the dawn, but no crescent was ever reflected from the zenith into the still depths below. Only the larger moons rode into the night skies above him. His aching heart fought with despair and distrust of his tribal gods. The wrinkles deepened on his wan face. The cold nights of spring and fall bent the decrepit figure and whitened the withered locks. Time dealt harshly with the faithful watcher, nobly guarding his sacred trust.

One spring a few tattered shreds of a blanket clung to the rough roots. Heavy snow masses around the pine had slipped into the pool sometime during the winter, and carried with them a helpless burden. The melting ice had let it into the sombre depths below. The birds sang as before, the leaves came and went, and Mother Nature continued her eternal rhythm.

During a March gale the ancient pine tottered and fell across the open water. In the grim procession of the years it became sodden and gradually settled into the oozy bottom. Only the gnarled and decayed branch—the perch of the old heron—remained above the surface.

One night in early fall, when there was a tinge of frost in the air, and the messages of the dying year were fluttering down to the water from the overhanging trees, the full moon shone resplendent directly above the pool. The old heron turned his tapering head up toward it for a moment, plumed his straggling feathers for a while, nonchalantly gazed at the white skull that caught the moon’s light below the water near his perch, and relapsed into immobility. A rim of darkness crept over the edge of the moon, and the earth’s shadow began to steal slowly across the silver disk. The soft beams that glowed on the trees and grasses became dimmed and they retreated into the shadows. The darkened orb was almost eclipsed. Only a portion of it was left, but far down in the chill mystery of the depths of the pool, among countless stars, was reflected a crescent moon.

The magic of Topago’s medicine was still potent. The hour for the redemption of the red man had come, but he was no more. The mantle of the Genius of the Place had fallen upon the old heron. He was the keeper of the secret of his pool.