THE PLUTOCRATS

By Earl Howell Reed

The Game Warden and his Deputy

THE invitation of the old shipmates to remain with them for a while was gratefully accepted. The witchery of the changing landscapes and the color-crowned dunes was irresistible. The society of my odd friends, which was full of human interest, and certain beguiling promises made by Narcissus, were factors that prolonged the stay.

After a week of blustery weather, and a light fall of snow, the haze of Indian Summer stole softly over the hills. The mystic slumberous days had come, when, in listless reverie, we may believe that the spirits of a vanished race have returned to the woods, and are dancing around camp fires that smoulder in hidden places. Spectral forms sit in council through the still nights, when the moon, red and full-orbed, comes up out of a sea of mist. Smoke from phantom wigwams creeps through the forest. Unseen arrows have touched the leaves that carpet aisles among the trees where myriad banners have fallen.

Our drift-wood fire glowed on the beach in the evening. Sipes piled on all sorts of things that kept it much larger than necessary. With reckless prodigality, he dragged forth boxes, damaged rope, broken oars, and miscellaneous odds and ends, that under former conditions would have been carefully kept.

Sipes and Saunders were in high spirits. They walked with an elastic swagger that bespoke supreme confidence in themselves, and a lofty disdain of the rest of the world. There was much discussion of plans for the future.

“We got all kinds o’ money now, an’ we c’n spread out,” declared Sipes. “We gotta git ol’ John an’ ’is horse down ’ere, an’ take care of ’em. That ol’ nag’s dragged millions o’ pounds o’ fish ’round fer us, an’ ’e oughta have a rest. They’r’ both git’n’ too old to work any more, an’, outside o’ me an’ Bill an’ Cookie, them’s the only ones that lives round ’ere that’s fit to keep alive through the cold weather.

“We gotta haul down that ol’ sign on the shanty, ’cause we’ve gone out o’ the fish business. We’r’ goin’ to fix this place all over. All them fellers that has money, an’ lives in the country, an’ don’t work, has signs out that’s got names on ’em fer their places. I drawed out the new sign with the pencil yisterd’y, an’ this is wot it’s goin’ to be.”

He unfolded a piece of soiled wrapping paper, on which he had rudely lettered—$HiPMATE$ RE$T

“The names won’t be on it, but shipmates’ll mean us all right. The sign’ll still look like cash-money, an’ you bet we’r’ goin’ to rest, so that sign’s all right, an’ she’s goin’ up.”

Catfish John and Napoleon arrived the next morning.

“You can’t git no more fish ’ere!” announced Sipes, after he had made his usual derisive comments on the old peddler’s general appearance. “This place ’as changed hands. Some fellers own it now that don’t ’ave to work. You’r’ a wuthless ol’ slab-sided wreck, an’ you ain’t no good peddlin’ fish. You oughta be ’shamed o’ yerself. Yer ol’ horse is a crowbait, an’ yer fish waggin’s on the bum. You git down offen it an’ come ’ere. We got sump’n we want to tell you.”

John willingly admitted that all the charges were true, as he slowly and painfully descended from the rickety vehicle.

“Now listen ’ere, John,” continued Sipes seriously, “us fellers ’as got rich out o’ the jools wot we fished out o’ the river. We’r’ jest goin to set ’round an’ look pleasant, an’ quit work’n. You’ve been our ol’ friend fer years, an’ we got enough to keep you an’ Napoleon in tobaccy an’ hay fer the rest o’ yer lives. You’re a nice pair, an’ if you’ll go in the lake an’ wash up, we’ll burn all yer ol’ nets, an’ the other stuff up to your place, an’ yer ol’ boat, too, an’ you c’n come down ’ere an’ live. We don’t want none o’ them things ’ere, fer it ’ud make us tired to look at ’em. We don’t want to see nothin’ that looks like work ’round ’ere, no more’n we c’n help, but you gotta help haul some lumber. We’r’ goin’ to tack some more rooms on the shanty. It ain’t a fit place fer fellers like us to live in.”

John was greatly pleased over the good fortune that had come to his friends, and happy over the plans that had been made for his future. He said little, but I noticed that his eyes were moist as he limped over to the shanty to be “interduced to Cookie.”

“Ah ce’t’nly am glad to meet you, Mr. Catfish!” said Narcissus, cordially, as they shook hands. “Ah’ve hea’d a great deal ’bout you f’om these gen’lemen. Ah would like to make a li’l cup o’ coffee fo’ you. Jest have a seat an’ Ah’ll have it ready in jest a few minutes.”

John looked at him gratefully and sat down. He was much impressed by the evidences of prosperity around him. The old pine table was covered with a cloth that was spotless, except where Sipes had spilled a “loose egg” on one corner of it. There was a bewildering array of new clean dishes and kitchen utensils about the room, and some boxes that had not yet been unpacked. Narcissus had been given carte blanche as to the domestic arrangements. He was chef, valet, major domo, and general manager.

“Cookie’s boss o’ the eats an’ the beds, an’ ev’rythin’ else ’round the house, ’cept drinks,” declared Saunders.

He had made several trips to the village with the old cronies and they had acquired a large part of the stock of the general store. Their advent must have been a godsend to the aged proprietor.

“Now, John,” said Sipes, after the old man had finished his coffee, “you c’n go back to yer place jest once, an’ fetch anythin’ you want to keep that’s small, but don’t you bring nothin’ that weighs over a pound, an’ then you come an’ sleep in the cabin o’ the Crawfish till we git the new fix’n’s on the shanty. We’ll feed you up so you’ll feel like a prize-fighter, an’ we’ll make Napoleon into a spring colt. He c’n stay in the work-shed ’til we make a barn fer ’im. We’r’ goin’ up there tomorrer night, an’ we’r’ goin’ to burn up the whole mess wot you leave, an’ you can’t go with us. We’ll chuck ev’rythin’ into that cusséd ol’ smoke-house, an’ set fire to it. Tomorrer night’s the night, an’ don’t you fergit it!”

John stayed for a couple of hours, but did little talking. Evidently he was deeply touched. He drove away slowly up the beach toward the only home he had known for many years. His quiet, undemonstrative nature was calloused by the unconscious philosophy of the poor. Gratitude welled from a fountain deep in his heart, but its outward flow was restrained by the rough barriers that a lifetime of unremitting toil and poverty had thrown around his honest soul.

He returned late the following afternoon. His wagon contained a few things that he said he wanted to keep, no matter what happened to him.

“Thar ain’t no value to the stuff I got ’ere, ’cept to me. If you’ll put this in a safe place ’til things git settled, I’ll be much obliged,” said the old man, as he extracted a small package from an inside pocket. He carefully opened it and showed us an old daguerreotype. A rather handsome young man, dressed in the style of the early fifties, sat stiffly in a high-backed chair. Beside him, trustfully holding his hand, was a sweet-faced girl in bridal costume. Pride and happiness beamed from her eyes.

“That thar’s me an’ Mary the day we was married. She died the year after it was took,” said the old fisherman, slowly. There was tenderness in the quiet look that he bestowed on the picture, and the care with which he rewrapped it and handed it to Saunders for safe-keeping.

The old daguerreotype had been treasured for over half a century. I knew that tears had fallen upon it in silent hours. Its story was in the old man’s face as he turned and walked over to his wagon to get the rest of his things.

“Now, hooray fer the fireworks!” shouted Sipes, when we had finished our after-dinner pipes in the evening. By the light of the lantern, the small row-boat was shoved into the lake. John watched the sinister preparations with misgivings. As we rowed away, Sipes called out cheerily, “Now you brace up, John; you ain’t got no kick comin’! You c’n stay an’ play with Cookie. He’ll make you some more coffee, an’ you’ll find a big can o’ tobaccy on the shelf.”

The old shipmates did not intend that any lingering affection that John might retain for his old habitat, or any heartaches, should interfere with his enjoyment of his new home, or with their delight in burning his old one. They had grimly resolved that the transition should be complete and irrevocable.

We reached the old fisherman’s former abode in due time. We found the tattered nets wound on the reels, which were old and much broken. We piled all of the loose stuff on the beach around the nets, and the leaky boat was set up endwise against them. With the lantern we explored the disreputable little smoke-house. It was filled with fish tubs, bait pails, and confused rubbish, and was redolent with fishy odors of the past that Saunders declared “a clock couldn’t tick in.”

We climbed up to the shanty on the edge of the bluff. The door of the ramshackle structure was fastened with a piece of old hitching strap that was looped over a nail. We entered and looked around the squalid interior. Four bricks in the middle of the room supported a nondescript stove. A rough bench stood against the wall, and a few tin plates, cups, and kettles were scattered about. The only other room was John’s sleeping apartment. A decrepit bedstead, that had seen better days and nights, an old hay mattress, a couple of much soiled blankets, a cracked mirror, some candle stubs, and two broken chairs were the only articles we found in it.

“All some people needs to make ’em happy is a lookin’ glass,” observed Sipes, “but ol’ John ain’t stuck on ’imself; wot does ’e want with it? He prob’ly busted it w’en ’e peeked in it to see if ’is ol’ hat was on straight.”

“I hope John’s got some insurance on this place,” Saunders remarked, as he dragged the mattress to the wall and piled the bedstead and chairs on it. We found a bottle half full of kerosene under the bench, which we emptied over the floor.

“Now gimme a match!” demanded Sipes.

When we reached the foot of the bluff the flames were merrily at work above us. The smoke-house, and the stuff accumulated around the nets, were soon on fire. We next visited Napoleon’s humble quarters on the sand, and another column of smoke and flame was added to the joy of the occasion.

“We can’t leave fer a while yet,” said Saunders; “no fire’s any good ’less somebody’s ’round to poke it.”

We spent considerable time watching the fires, to assure ourselves that the destruction was complete, and that there was no possibility of the flames on the bluff getting into the woods beyond through the dry weeds on the sand. There was a light off-shore breeze, so there was little danger.

“That ol’ joint’s clean at last,” observed Sipes, as we rowed away in the early hours of the morning.

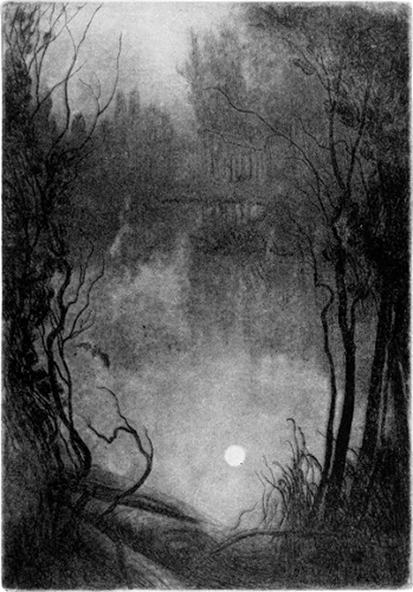

From far away we looked upon the scene of Catfish John’s dreary life, illumined by gleams from the smouldering embers that played along the face of the bluff.

There were essentials that the old man’s humble surroundings had lacked. Long sad years were interwoven with them, but the faded face in the old daguerreotype may have lighted the dark rooms and helped to make the lonely place an anchorage, for is home anywhere but in the heart? It does not seem to consist of material things. Absence, estrangement, and death destroy it—not fire. Sometimes, out of the losses and wrecks of life, it is rebuilded, but not of wood and stone.

I arranged with John to transport my few belongings to the railroad station the next day, and regretfully left the contented old mariners and their happy “cookie,” who was no small part of the riches that had come from the Winding River.

On the way through the hills the old man opened his heart.

“Now wot d’ye think o’ them ol’ fellers? They battered ’round the seas an’ they been up ag’in pretty near ev’rythin’ they is. They come in these hills an’ settled down to fish’n’. We alw’ys got ’long well together. I done little things fer them an’ they done little things fer me. Sipes is a queer ol’ cod, an’ so’s Saunders, but all of us has quirks, an’ they ain’t nobody that pleases ev’rybody else. Now them ol’ fellers has got rich. I don’t know how much they got, but w’en anybody gits a lot o’ money you c’n alw’ys tell wot they really was all the time they didn’t have it. They’r’ all right, an’ you bet I like ’em, an’ I alw’ys did. They drink some, but they don’t go to town an’ go ’round all day shoppin’ in s’loons, like some fellers do. Mebbe they’ll git busted some day, an I c’n do sump’n fer ’em like they done fer me.”

I bade my old friend farewell on the railroad platform and departed.

In response to a letter sent to him in January, John was at the station when I stepped off the train one crisp morning a week after I wrote, but it was a metamorphosed John who stood before me. He was muffled up in a heavy overcoat and fur cap. He wore a gray suit, new high-topped boots, and leather fur-backed gloves. I hardly recognized him. Much as I was delighted with these evidences of his comfort, there was an inward pang, for the picturesque and fishy John, who had been one of the joys of former years, was gone. This was a reincarnation. The strange toggery seemed discordant. Somehow his general air, and the protuberance of his high coat collar above the back of his head, suggested an Indian chief, great in his own environment, who had been rescued out of barbarism and debased by an unwelcome civilization. He was like some rare old book that had been revised and expurgated into inanity.

“I got yer letter,” said the old man, after our greetings, “an’ ’ere I am! I yelled out at ye, fer I didn’t think you’d know me. What d’ye think o’ all this stuff them ol’ fellers ’as got hooked on me?”

Napoleon, sleek and apparently happy, with a new blanket over him, was standing near the country store, hitched to a light bobsled.

I congratulated the old man and inquired about our mutual friends. After we had put the baggage and some supplies from the store into the sled, we adjusted ourselves comfortably under a thick robe, and Napoleon trotted away on the road, with a merry jingle of two sleigh-bells on his new harness.

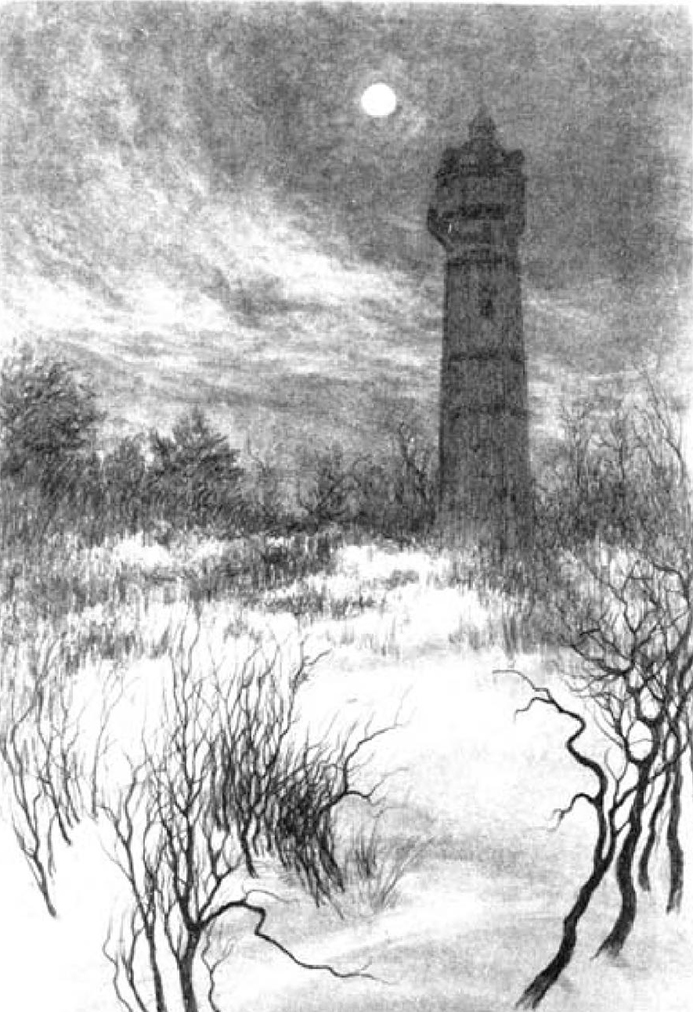

There were no tracks on the road after we got into the wooded hills, except those made by Napoleon and the sled a couple of hours before, and the cross trails of rabbits and birds that had left the tiny marks on the snow, in their search for stray bits of food that the frost and winter winds might have spared for their keeping.

Nature in her nudity is prodigal of alluring charms on her winter landscapes. The forests, cold, still, and bare, stretched away over the undulating contours of the dunes in their mantle of snow. The lacery of naked branches, silvered with frost, was etched against the moody sky.

He who is alone in the winter woods is in a realm of the spirit where the only borders are the limits of fancy. The big trees, like sentinels grim and gray, seem to keep watch and ward over the treasures that lie in the hush of the frozen ground, where a mighty song awaits the wand of the South Wind. The winding sheet that lies upon the white hills hides the promise as well as the sorrow. The great mystery of earth’s fecundity that is under the chaste raiment of the snow is the mystery of all life, and to it the questioning soul must ever come. The message of our loved ones, who are under the white folds, may be among the petals of the flowers when they open.

ON THE WHITE HILLS(From the Author’s Etching)

When we descended the steep road to the beach, we saw Shipmates’ Rest in the distance. Saunders came out to greet us on our arrival. He was enveloped in a heavy reefer, and wore a rather sporty-looking new cap. He conducted us into what was once the fish shanty, but, alas, what a change! It had been almost entirely rebuilt. There were five rooms. A stairway led to a trap door in the roof, above which was a railed-in, covered platform. A stone fireplace had replaced the old stove, and there was a large new cook stove in the kitchen, where Narcissus reigned supreme. I was struck with the almost immaculate cleanliness of the place. While the architecture was nerve-racking, and seemed to pursue lines of the most resistance, it looked very comfortable.

“Sipes is out hunt’n rabbits. He’ll be back shortly,” said Saunders. “You jest hang up yer things an’ make yerself to home. Cookie’s out back undressin’ some fowls, an’ ’e’ll be glad to see you.”

Narcissus soon appeared with a grin on his honest face.

“Ah ce’t’nly am glad to see you down heah again!” he exclaimed. “Ah was just fixin’ some chick’ns, an’ tomorrow we’ll have a fracassee with dumplin’s. Chick’ns have to wait ovah night in salt watah fo’ they ah cooked, but we got pa’tridges fo’ today. Ah you fond of them?”

Idle questions, propounded simply to make conversation, often inspire doubt of normal mentality. I had brought a new mouth organ and a ukelele for him from the city, and his delight over the little gifts quite repaid their cost.

My old friend Sipes arrived during the next hour, without any rabbits, and we had a happy reunion over the delicately roasted partridges. There were six of them, with little bits of bacon on their breasts—like decorations for valor on the field.

Sipes presided at the head of the table with the air of a medieval robber baron who had returned to his castle from a successful foray. A napkin was tied around his neck, and he wielded his knife and fork with impressive gusto. Prosperity had begun to bubble. I was told the prices of everything in sight, and informed of the cost of the glass that he had used to make a small skylight in the north room, so as to adapt it for a studio. In the fall I had jokingly alluded to something of this kind, but had no idea that it would be included in the plans. Compensation was grandly refused.

“You’r’ in on all this, an’ we want you to stick ’round ’ere w’en you ain’t got nothin’ else to do. You knowed us w’en we didn’t ’ave a dollar, an’ you thought jest as much of us, so you quit talkin’ ’bout payin’ fer sky-view glass. There’s nothin’ doin’!”

During the afternoon we heard intermittent strains of “Money-Musk” from the new mouth organ in the kitchen, accompanied by experimental fingering of the ukelele. Narcissus had devised an ingenious framework, which he had put on his head, to hold the mouth organ in place, and enable him to use his hands for the other instrument, but it was only partially successful.

One of the objects of the winter visit was to make some sketches of Saunders and Narcissus for this volume, which had been neglected during the fall. They seemed pleased, and were willing models. Saunders insisted on wetting and combing his hair carefully, and getting into stilted attitudes. He was finally persuaded to let his hair alone and wear his old cap. He was anxious that his ancient meerschaum pipe should be in the picture. It seeped with the nicotine of many years.

“The tobaccy that’s been puffed in that ol’ pipe ’ud cover a ten-acre lot,” he declared, and I believed him. “You can’t show that in the pitcher, but you c’n make it look kind o’ dark like. Gener’ly I smoke ‘Bosun’s Delight’ an’ it’s pretty good. It’s strong stuff an’ none of it ever gits swiped.”

When the drawing was finished he criticized it severely, which was quite natural, for no human being is entirely without vanity. Portrait artists, like courtiers, must flatter to succeed.

Narcissus also wanted a pipe in his picture. He thought it would look better than a mouth organ, and, as it was much easier to draw, I humored him. He posed with unctuous ceremony, and assumed some most serious and baffling expressions.

Sipes watched the proceedings with interest, and enlivened them with running comment.

“I been through all that lots o’ times. You fellers ain’t got nothin’ on me, an’ if you ever git in a book you’ll look like a couple o’ horse thieves. I know wot e’ done to me.”

The disapproval of these particular sketches was probably deserved. It is a fact, however, that, while readily admitting limitations in other fields of knowledge, there are few people who hesitate to criticize any kind of art work authoritatively. Their immunity from error seems to them remarkable, and to be the result of a natural instinct that they have possessed from childhood. “I know what I like” is a common and much abused expression. They who use it usually do not know what they like or what they ought to like. The phrase covers infinite ignorance, with a complacent disposition of the subject. The assumption of critical infallibility is complete before a portrait of the critic.

Many otherwise intelligent critics respect only age and established art dogma. The dead masters haunt pedantic essayists and opulent purchasers, who accept embalmed opinions that they would be incapable of forming for themselves. Extended consideration of this subject is out of place amid the landscapes of Duneland, where the shades of the justly revered old painters may have deserted their madonnas and be wielding spiritual brushes, charged with elusive tints that flow unerringly upon canvases as tenuous as the evening mists. On them filmy portraits of the old dwellers along the shore may take form and vanish with the morning light, for in these rugged faces are the same attributes that made humanity picturesque centuries ago. If one of these portraits could suddenly materialize, it would bring a staggering price, if there was no suspicion that a modern had painted it. Some stray rhymester has aptly said:

“If Leonardo done it,

It is a masterpiece.

If Mr. Lucas made it,

’Tis but a mass o’ grease.”

“We gotta git some pitchers fer them walls,” declared Sipes, “an’ you buy ’em fer us. Git some colored ones that’s got boats in ’em, an’ some fight’n scenes. I’d like to git a nice smooth han’-painted pitcher o’ John L. Sullivan, an’ I don’t care wot it costs!”

The old man wanted these things to enjoy. His purse pride had not yet suggested the idea of posing as a connoisseur and condescending patron of the enshrined dead, without love or understanding of what they did, but the germs were there that might enthrall him in the future, for affluence sometimes begets strange vanities.

Great masses of ice had been tumbled and heaped along the shore by the winter waves, and we saw little of the lake, except when we climbed the bluffs. The winds howled over the desolate beach at night in angry portent, and one morning a driving storm came out of the north. Occasionally, from somewhere out above the waves that thundered against the ice, we could hear plaintive cries of gulls that groped through the blinding snow. The drifts piled high against the bluffs on the wild coast. The flying flakes were swept along in thick clouds by the fury of the gale. The house was almost buried. The wind subsided after about twenty-four hours, but the snow continued and fell ceaselessly for three days.

When the skies cleared we opened the trap door to the “crow’s nest,” the covered platform over the roof, and looked out over the white waste. A few straggling crows accented the immaculate expanse, the blue billows were pounding the ice packs, and a part of the mast of the Crawfish protruded in the foreground, but everything else was white and still.

We were snowbound for ten days, but contentment reigned at Shipmates’ Rest. We dug deep paths that enabled us to reach our water supply, and to communicate with Napoleon in his cosy little barn in the ravine.

The plentiful supply of canned goods, that Narcissus had wisely laid in, was drawn upon for sustenance.

“Them air-tights is life savers!” exclaimed Sipes, as he mixed up some lobster, lima beans, ripe olives, and prunes on his plate. “Wot’s the use o’ monkeyin’ with them fresh things w’en you c’n git grub like this that’s all cooked an’ ready? All ye need is a can opener to live up as high as ye want to go. Gimme some o’ that pineapple fer this lobster, an’ pass John them dill pickles!”

“You better let Cookie chop up that mess fer you an’ squirt some lollydop on it, an’ eat it with a spoon,” advised Saunders; “yer git’n’ it all over us!”

“It’s too bad they can’t can pie,” said Sipes, “but we got pudd’n’s. Hi, there, Cookie, fetch some o’ them little brown cans an’ tap ’em!”

Narcissus appeared with a delicious cranberry pie, “with slats on it,” and the pudding was forgotten.

“This is the life!” continued the old man, as he broke some crackers into his coffee, “wot do we care fer expense?”

Our evenings were spent in various interesting ways. John and Narcissus had grown very fond of each other, and they spent much time playing checkers. Numberless sound waves went out into the dark, over the cold snow, that came from music, laughter, and rattling poker chips.

There are many hardships in this life, both real and imaginary, but being snowbound at Shipmates’ Rest is not one of them.

A typical January thaw set in, and the warm sunshine released us from our feathery bondage. The Crawfish was floated out on to the still lake, and we voyaged to the little town at the mouth of the river, from where I took the train for the grimy, noise-cursed city—cursed, indeed, for the unnecessary and preventable dirt and noise in most of our cities would hardly be tolerated in Hades.

It was August when I again visited Shipmates’ Rest. There was a lazy calm on the lake, and a delicate and peculiar odor from the evaporating water. Scattered flocks of terns, nimble-winged and graceful, skimmed over the surface, and dipped, with gentle splashes, for minnows that basked in the sun. The still air over the sandy bluffs shimmered in the heat.

I found my friends in the lake, where they had gone to get cool, and soon joined them.

There were more transformations on the beach. A mouse-colored donkey stood in the shade of the house, regarding us with wise and sleepy eyes. A black puppy gambolled at the water’s edge, clamoring for attention. A cow, which I recognized as “Spotty,” stood in the creek that flowed out of the ravine, peacefully chewing her cud and switching flies with her abbreviated tail. A couple of white pigs were squealing and grunting in a pen near the little barn, and about a dozen fluffy brown hens, attended by a dignified rooster, were wandering over the sand after stray insects. A tall flag-pole extended above the “crow’s nest” on top of the house.

All these things were explained at length, as we stood out on the smooth sandy bottom, with the cool water around our necks.

“That anamile wot’s huggin’ the house,” said Sipes, “is to hitch to the windlass w’en we have to haul the boat out. Cookie calls ’im Archibald, but ’is real name’s Mike. He goes ’round an’ ’round with the pole, like we used to do, an’ winds up the rope. W’en we want to run the boat in the lake, we got a block an’ tackle wot’s lashed to that spile out’n the water. We take the rope out from the boat to it, an’ run it back to the windlass, an’ Mike winds ’er out fer us. That kind o’ work ain’t fit fer nobody but a jackass, an’ ’e wouldn’t do it if ’e had money. Mike strays ’round the country a good deal at night fer young cabbage an’ lettuce an’ things, but he’s gener’ly ’ere on deck in the mornin’. Cookie bought ’im an’ the pup in the village this summer. We gotta have a pup, but he’s a cusséd nuisance. W’en ’e’s in ’e yelps to git out, an’ the minute ’e’s out ’e howls an’ scratches to git in. It takes ’bout all o’ one feller’s time to ’tend ’im, but ’e’s lots o’ company. He’ll bark if anybody snoops ’round at night. They’s val’ables ’ere an’ we gotta look out. We call ’im Coonie, an’ ’e’s some dog. Cookie’s teachin’ ’im a lot o’ tricks, an’ w’en ’e grows up ’e’ll be good to chase patritches out o’ the brush.

“We bought Spotty off o’ the Ancient up the river, an’ Cookie towed ’er in ’long the road through the hills with a rope. Somehow I alw’ys liked that ol’ girl, an’ we gotta have milk.

“Them squealers is to eat wot’s left out o’ the kitchen, an’ next winter they’ll quit squealin’. Them hens is from the village, too, an’ their business is to make aigs. Next year we’ll have slews o’ young chicks, an’ some w’ite ducks. Cookie’s got a rubber thing wot ’e fastens on that rooster’s bill ev’ry night w’en ’e puts ’im to bed, so ’e can’t crow an’ roust us out in the mornin’.

“We got a compass an’ a binnacle an’ a new spy-glass up in the crow’s nest. Me an’ Bill an’ John set an’ smoke up there in the shade an’ see fellers work’n way off, an’ watch Mike windin’ up the boat.”

“Tell ’im ’bout the motor, long as yer goin’ to keep this up all day,” interrupted Saunders.

“Oh, yes. We got a new one wot’s built in aft o’ the cab’n. It’s got two cylinders, an’ it works fine. We buried the old one up ’side o’ Cal’s dog. It ’ad to be that er us. Bill, you keep still w’en I’m talk’n!

“The mast an’ them halyards over the house is to fly signals. W’en we’r’ up er down the beach, er out buzz’n on the lake, Cookie runs up the mess flag w’en it’s dinner time. He uses red with w’ite edges fer chops an’ steaks, an’ the w’ite one with a round yellow splotch in the middle means aigs wot’s been poached. He flys that, an’ a square o’ calico under it, w’en we’r’ goin’ to have corn beef hash an’ aigs on top of it. He runs up a big bunch o’ cotton cords w’en ’e’s made oggrytong speggetties, an’ w’en the flag’s plain brown, it means beans. There’s no knowin’ wot that cookie’s goin’ to do next.”

A cool breeze came up in the evening and we built our usual fire on the beach, more for its subtle cheer than its heat, and talked over reminiscences of the big snow-storm, and things that had happened since.

The old sailors were in a state of opulent bliss. All of their desires were satisfied, except, as Sipes expressed it, “git’n even with two er three fellers I know of,” and happiness reigned in their simple hearts.

Out of the tempests of many seas, their battered ship had come, and was anchored in a haven of tranquillity. The languor that comes with satiety and completion was stealing gently over them. Life presented no riddles, and they were without illusions. So far as their capacity for enjoyment extended, the fair earth and the fulness thereof was theirs. The great blue lake, the floating clouds, the jewelled fire of the sunsets, and the star-decked firmament belonged to them, as much as to anybody else. Title deeds to the sands, vine-clad hills, woods, and to the open fields, where suppliant petals drink the rain, could not add to their sense of possession.

Every comfort was around them that their limitations could require. They were spared the inanities and shallow snobbery of “society,” and the many other ills that come with existence in a sphere of vanity and hypocrisy. The gates of higher knowledge were not opened to them. Art, science, and literature lay in garnered hoards far beyond their ken, but after their lives are closed, who may judge of the futility, or award the laurel?

Into this happy Arcady—this land of the heart’s desire and hope’s fruition—softly prowled the onion-skinner. Like an evil wind upon a flowery lea, he crept out of the north over the wide waters. He landed at the beach with a boat on the still morning of a day that had promised to be bright and fair. Eveless though this garden was, Satan had entered.

Horatius T. Bascom was a man of perhaps forty-five. His closely cropped moustache was slightly gray. Under it was a mouth like a slit in a letter-box. It seemed to have a certain steel-trap quality that savored of acquirement but not disbursement. His eyes had a shrewd, greedy expression, and, when he frowned, small wrinkles formed between them that somehow suggested the lines of the dollar sign—that sordid mark that disfigures great characters and destroys small ones.

He was the type of man who signs his business letters with a rubber stamp facsimile signature, to facilitate legal evasion in the future. Such letters, insulting to the recipient, are also often stamped with a small inscription to the effect that they were “dictated, but not read” by the cautious sender. Altogether his personality was such as to prompt one to protect his watch pocket with one hand and his scarf pin with the other while talking with him.

“Hello, boys!” he called out glibly, as he walked up to our group. “You seem quite cosy around here. Have some cigars.” He produced a handful and passed them around. We all happened to be smoking, and Sipes was the only one who accepted the proffered weed. He put it in his pocket, with the remark that he would “smoke it some other time”—a phrase that the giver always inwardly resents, but the wily old man may have intended it to offend.

We were not particularly enthusiastic over his descent into our little circle.

“You look pretty cosy yerself,” said Sipes; “how much did you git fer that big jool you gouged us out of?”

“I sold it at a loss. It had a small imperfection that I didn’t notice when I bought it. You certainly got the best of that bargain.”

“They wasn’t no imperfection in yer bunch o’ bunk w’en you was buyin’ it.”

We kept rather quiet and let our caller lead the conversation, hoping that the object of his visit would finally unravel from the tangle of his small talk. Coonie sniffed around him a few times, and, with unerring instinct, retreated under the house.

The atmosphere of hostility that enveloped his coming gradually dissipated during the forenoon, and he was invited to join us when Narcissus announced lunch.

“Now what you fellows ought to do,” he declared, “is to go up the river again and drag it more thoroughly. I think you’d find some more pearls there that would put you well on your feet financially. You could buy some land on the bluff and along the shore and have a larger place. This property will all be much more valuable some day. You could have an automobile, and keep more servants. If you had a bigger and better boat you could put a small crew on it and go anywhere in the world you wanted to.”

He outlined methods of using money that dazzled imagination. Like Moses of old, Sipes and Saunders were shown a land of allurement, from what seemed to them a towering height. It could be theirs, if they had the price, and the price was in the lily-margined channel of the Winding River.

Like most of the rest of humanity, the onion-skinner craved “unearned increment,” and he hoped to inveigle his hearers into procuring it for him. The echo of the coin’s ring—a sound that encircles the world—was in the voice of the tempter, and the old mariners listened as to a siren’s song.

“I’ll go with you, if you’d like to have me,” he declared, “and I’ll pay you a good price for your pearls, as I did before.”

“I’ll tell ye wot we’ll do,” said Sipes. “We ain’t busy now, an’ we’ll take the Crawfish up to our ol’ camp. We’ll take Cookie ’long an’ keep things up. You c’n go out with the flatboat an’ fish fer jools. We’ll stick ’round an’ watch you work, if we don’t git too tired, and we’ll give you a fifth o’ wot you git. We’ll sell our jools to somebody else, an’ w’en you sell your share you c’n fix up with us fer our time. If you don’t find nothin’ you won’t have to pay us much anyway, so it’ll be a good thing fer you.”

While the proposition might have excited the onion-skinner’s admiration, from a professional point of view, he failed to see its advantages to him. He suggested that it might be well to think matters over for a few days, and that he “might drop around again the latter part of the week.”

We helped him push his boat into the lake, and he rowed away, leaving a writhing serpent of discontent at Shipmates’ Rest.

“They’s a good deal in wot that feller says,” declared Sipes. “I don’t think nothin’ o’ him, but jest think wot we c’d do if we had two bar’ls o’ cash-money instid o’ one! We c’d branch out an’ buy this whole cusséd shore. We’d stick up signs and nobody’d dast come on it!”

Saunders was virulent and profane in his comment on “fellers that ain’t satisfied with wot they got, w’en they got all they need, er ever oughta have,” but finally admitted that “they’s a lot more things we might do if we c’d find some more o’ them big pearls.”

That evening the old cronies departed into the moonlight for consultation. John and I sought our couches early. Narcissus took his new mouth organ and ukelele, and strolled off up the beach with Coonie. They had evidently returned sometime before midnight, for I heard loud imprecations being bestowed on the pup by Saunders, who had found him chewing up a deck of cards on the floor, when he and Sipes had come in later. Doubtless Coonie had been ennuied and distrait, and had longed for occupation. With all his sins, he was a lovable little dog, and his good nature and affection made him irresistible. He was fully forgiven in the morning.

“Bill an’ me’s talked this thing all over,” announced Sipes at the breakfast table. “This damn onion-skinner’s got sump’n else in ’is head ’sides jools. He wouldn’t want to go up there an’ stick ’round jest to watch us clam-fish’n’. We’ll find out wot’s bit’n’ ’im. We’r’ goin’ to tell ’im to come on with us, an’ we want you to go too. We’ll go up there an’ start the camp an’ do some jool-fish’n’, an’ have a good time, an’ mebbe we’ll git some. That cuss bilked us on that deal last year, an’ you bet we’r’ goin’ to git square somehow. We’r’ goin’ to give ’im the third degree, an’ you jest watch us fondle ’im. All such fellers as him oughta be exported.”

Bascom was received with faultless urbanity when he came again. It was agreed that he should be simply a guest, and that operations should be resumed on the old basis. Sipes assured him that he would be made comfortable.

“You’ll have a fine time up there in them woods. You c’n fish an’ loaf ’round an’ pick posy flowers, an’ us fellers’ll find out wot’s left in the river. Cookie’s goin’ to fix up a lot o’ stuff, an’ we’ll have a fine trip. You go an’ fetch wot you want to take ’long, an’ come early tomorrer.”

The necessary preparations were made. Mike wound the Crawfish into the lake. Bascom had brought some seedy old clothes, a soft gray hat, and some high boots. His baggage was light and he appeared quite well prepared for an outing. He had some interesting maps with him, which he said would enable us to keep posted as to exactly where we were. He brought a pocket compass, some light fishing tackle, a leather gun case, and I noticed, when his coat was off, that the handle of a small revolver protruded from his left hip pocket.

John was to remain in charge of the place.

“Now don’t you take in no bad money, an’ don’t you pay out none o’ no kind w’ile we’r’ gone,” cautioned Sipes, as we climbed into the boat. “You take care o’ yerself, an’ don’t fall in the water.” He bestowed a solemn wink on the old man as the motor began to hum, and we departed, waving farewells to our faithful custodian.

The voyage to the mouth of the river was uneventful. We tied up at the old pier, and Sipes and Narcissus left us for an hour to do some errands in the village. A former experience of Narcissus in that town was disastrous, and the old man thought “somebody’d better be ’long to help Cookie carry things, fer ’e got overloaded ’ere once’t.”

Saunders and I found my small boat and tent where they had been stored during the winter, and got them out to take with us.

“That feller that Sipes is talk’n’ to up there on the hill’s the game warden,” remarked Saunders. “Wot d’ye s’pose ’e wants with ’im?”

We reëmbarked, made our way up through the marsh, and saw our old camping ground in the distance.

Out in the middle of the river we beheld Captain Peppers on the flatboat, which we had left on the bank the year before. He had been dragging the stream, but had stopped work when he heard our motor in the marsh.

“Look at that ol’ pussyfoot up there fish’n fer jools!” exclaimed Sipes. “He looks like a bug float’n on a chip. You c’n see ’is ol’ beak from ’ere! Listen at me josh ’im w’en we git up to ’im. He gives me pains. I’d like to know wot ’e was ever cap’n of. It’s prob’ly one o’ them demijohn titles. They’s slews of ’em. Fellers that drinks a lot gits to be called Colonel an’ Major an’ Cap’n, that ain’t never c’mmanded nothin’ er fit nothin’ but demijohns all their lives, an’ I bet ’e’s one of ’em. The redder their noses gits the higher up their titles goes, an’ some of ’em gits to be gen’rals ’fore they’r laid away, an’ they’s some s’loon jedges over to the county seat that ain’t never been in no court ’cept to be fined fer bein’ drunk. Don’t you start nothin’ ’bout that ol’ motor, Bill, ’cause it won’t do now.”

“Hello, Cap’n!” shouted the old man, as we came up. “Fine day, ain’t it? Cetchin’ any mudturkles?”

The Captain, ill at ease, began poling the flatboat toward the bank.

“I didn’t know you expected to use this outfit again, an’ I thought I’d see if they was any loose pearls layin’ ’round ’ere. Of course now you’re here you c’n go ahead. I don’t want to interfere with you in no way.”

“You won’t,” replied Sipes. “We didn’t know you was clam-fish’n w’en we fust seen you. We thought you’d mosied up ’ere so’s to be near that spring, an’ was jest out cruisin’ on the river fer fun.”

The Captain’s nose was a little redder than when we last saw him, but otherwise he appeared unchanged. He was invited to land and have lunch with us. Saunders introduced him to the onion-skinner, liquid cheer was produced, and an entente cordiale soon prevailed.

The big sail was again rigged as a shelter tent in its old place, and my tent was put where it was before. The Captain kindly helped to get our camp in order. He showed us a few pearls of moderate value, that he had found during the two weeks he had been at work on the river, and they were purchased by Bascom, at what seemed to be a fair price. Late in the afternoon he partook of more liquid cheer, and rowed away down the river in his little boat.

That night we assembled around the fire, but the circle was not as of old. Something was missing and something had been added. The atmosphere was unsympathetic. There is a certain psychology that pervades gatherings, both great and small, that is subtly sensitive to influences that are often indefinable. In this instance the “repellent aura” was obviously the onion-skinner. He exerted himself to be agreeable, but his bonhomie was about as infectious as that of a crocodile trying to be playful. His personality did not harmonize with the little amenities of life, and he was a misfit anywhere but in a financial transaction.

Sipes’s habitual effervescence seemed to have a false note. Saunders and I kept rather quiet, and the melodies that dwelt in the volatile soul of Narcissus were hushed.

The arboreal katydids were abroad in the woods. These insects are exquisitely beautiful in their green gowns. Like many human creatures, they would be fascinating if they kept still, but they stridulate boisterously and persistently. Their scientific name—Cyrtophyllus perspicillatus—is only one of the things against them. The insects seldom move after they have established themselves in a tree for the night, and they often stay in one spot from early August, when they usually mature, until the fall frosts silence their penetrating clamor. The green foliage provides a camouflage that renders them practically undiscoverable, except by accident. We hunted for one particular offender with an electric flashlight and murderous intent nearly half of one night, without finding him. We hurled many sticks and clods of earth into the tree, but failed even to disturb his meter.

It is the male katydid that proclaims the troubles of his kind to the forest world. He begins soon after dark, and continues his work until morning. Curiously, the female is silent.

The loud dissonant sounds are produced by friction of the wings, which have hard, drumlike membranes and edges like curved files. He shuffles them with a continuity that is nerve-racking. Often I would suddenly start from sound sleep, with an indistinct apprehension of some impending peril.

One morning, after a haunted and vexatious night in the little tent, I found that the following impressions had crept over white paper during the hours of darkness, and lay beside the burned-out candle. They are the lines of one who suffered and should be read with reverence.

A DIABOLIC CADENCE

Into the choirs of the trees there has come a rasping, strident, and unholy sound. A fiend in green is mocking the transient year with mad threnody from his eyrie among the boughs.

In that suspended half consciousness that hovers along the margin of a dream, there seems to echo, out of some vast and awful chasm, a rumbling roar of rocks—from some abysmal smithy of the gods within the hidden caverns of the earth where huge boulders are being fashioned by giant hands, to be hurled up into space, to descend with frightful crash, and extinguish the life upon the globe.

In the agonized recoil of frenzied fancy from the borders of the dream, the demonic ceaseless sawing, of the arboreal fiend in green, arrests the fleeting phantoms of the brain, and, like a doleful tuneless tolling of a fractured funeral bell—like a barbaric song of sorrow over fallen warriors—the ripping, rasping, resonant notes mingle with the night wind, and drown the harmonious hum of drowsy insects, that kindly nature has sent into the world to lull somnolent fancy into paths of dreams.

After the gentle prelude of the crickets—and the lullabies of forest folk—like a mad discordant piper, he starts a strain of dismal dole, and files away the seconds from the onward hours. Mercilessly across the tender human nerves, that seem to span the taut bridge of a swaying violin, he sweeps a berosined and excruciating bow.

Prolonged wailing for a “lost or stolen” love may have disintegrated his vocal chords. His agonized and shattered heart may have sunk into hopeless depths, and all his articulate forces may have been transmitted to his foliated wings, when his belovéd was lured away by some unknown marauder—mayhap of darker green or lovely pink.

The errant pair may be hidden in a distant glade—or dingly dell—gazing upward through the leaves, wondering “what star should be their home when love becomes immortal,” and listening to him, as he scrapes the melodies out of the night with that infernal, insistent, and slang-infected song:

“She’s beat it—she’s beat it—she’s beat it—

Come back—come back—come back—

You skate—you skate—

You’ve swiped—you’ve swiped

My mate—my mate—my mate!”

Intermittently he seems to muffle the ragged rhyme, and merge into virulent vers libre—imagistic muse and amputated prose—containing sound projectiles, of low trajectory, that winnow the aisles of the forest for an erring spouse who has fled beyond the range of common rhyme.

Perhaps it’s all wrong—about this insect having loved—for love is a holy thing, and it may be that it abides not among the things that have wings and stings. It would seem that he who could trill this nerve-destroying song could know no love, or that it was ever in the world.

It may be that this emerald villain has been outlawed by his kind, and he’s filing, up there in the dark, on some terrible iron thing, that he’s sharpening to annihilate the tribe that banned him. He may be sawing of a branch, and, if so, I hope he’s straddling the part that’ll fall off when he’s through. Maybe he’s got some ex-friend up there, pinioned to the bark, and he’s boring him to death, by telling him the same thing—the same thing—the same thing—o’er and o’er and o’er.

I wish that some gliding fluffy owl, or other rover of the darkened woods, would only pause a moment, and divest the bough of this green-mantled wretch, and then that some mighty ravenous bird would collect the people we know, who come and scrape on something that’s inside of them—lay a sound barrage before us—fret the air with piffle, and with sorrows all their own—and chant a woeful ceaseless cadence, like the green arboreal fiend, whose sonorous and satanic notes assail us from the bough. Miscreated, malignant, and hellish though they and the fiend may be, they all revel in that rare joy that comes only to him who has found his life work.

For our sins must we be scourged, else, why are these people?

And,

Pourquoi—pourquoi—pourquoi—

Is this

Katydid—Katydid—Katydid?

After listening patiently to the reading of the production, my unfeeling prosaic friend Sipes remarked, “Gosh, we gotta git that insect ’fore it gits dark ag’in!”

The Ancient called the third day after our arrival, and spent the afternoon with us. Bascom seemed much interested in helping to entertain him, and got out his maps. On one of them was indicated the names of the owners of the different tracts of land, and we were surprised to learn that the old man was the possessor of the woods we were in, practically all of the land around the marsh, and a long strip of frontage on the lake. Captain Peppers was also a large owner of property along the lake.

The veiled motive of Bascom’s trip with us was now apparent. He wanted options for a year on a large part of these holdings, and was willing to pay what he considered a good price. It seemed that on the day we came, he had had some talk with the Captain on the subject, and they were to take the matter up again.

He wanted options only on the tracts with marsh and lake frontage, and argued that if they were improved the rest of the land would be made much more valuable. He had skilfully arranged his stage setting for the object of his trip, and claimed that the idea had just occurred to him while he was taking this little outing. He said that he accidentally happened to have the maps, and had brought them along to familiarize himself with the country he was in.

He made the Ancient a substantial offer for an option on most of his holdings, at a price that the old man did not seem inclined to consider, but he was open to negotiation.

“I been livin’ ’ere most all my life, an’ I’ve ranged ’round this ol’ marsh an’ them sand-hills so much that I wouldn’t know how to act if they wasn’t mine, but if you’ll git yer figgers up whar I c’n see ’em, mebbe we’ll talk about it some more.”

“You see,” said Bascom to Saunders, after the old settler had left, “this land idea is a sort of a side issue with me. I think that perhaps a little money might be made here, but I would have to take some big chances. You and Sipes talk with those fellows a little, and see if you can’t bring them around to business, and I’ll pay you something for it if they sign up. You might have some influence with them. Tell them that I mentioned to you that it was just a gamble with me, and probably there isn’t a chance in a hundred that I will exercise the options at all, and they will be ahead whatever they get out of me now.”

The old shipmates agreed to do what they could and the subject was dropped for the time being.

The accidental exposure of the contents of a long fat wallet that Bascom carried inside his vest revealed the fact that he had a large amount of money with him, much larger than could possibly be required for ordinary use. Evidently he was prepared to close the business with the owners of the land the moment their minds met.

“Holy Mike! Did ye see that wad?” whispered Sipes, who was awed by the magic of the gold certificates. “I’d like to know some way to git that wad,” he remarked later. “I’d play some seven-up with ’im fer some of it, but they’s sump’n ’bout ’im that makes me think it wouldn’t do.”

I realized that the despoiler was at the gates of the Dune Country. The foot of the Philistine was on holy ground. This man with a withered soul was an invader of sanctuary. He would tear the dream temples down that the centuries had builded. With steam shovels and freight cars he would level the undulating hills, and haul away their shining sands to a world of greed, where man does not discriminate. The wild life would flee from steam whistles that shrieked through the forests, and from smoke that defiled the quiet places. Belching chimneys and unsightly signs would befoul and deface the fair domain. With the beauty of the dunes he would feed a Moloch in the sordid town.

The peaceful marsh, and the river with its channel of silver light, would be invaded with dredges. Abbatoirs, tanneries, factories, and blast furnaces might come. The Winding River, with its halo of memories, would flow away with receding years, and a foul stream would carry the stain of desecration and filth out to pollute the crystal depths of the lake.

“Improvements” were contemplated in Duneland, and the spectre of hopeless ugliness hovered along its borders. The altar of Mammon awaited a sacrifice, for “money might be made here” if certain manufacturing interests, to which Bascom vaguely alluded, “could be induced to utilize these now practically worthless wastes of sand.”

In years to come the wild geese may look down from their paths through the soiled skies, to the earth carpet below them, and wonder at the creatures that have changed it from a fabric of beauty to a source of evil odors and terrifying sounds.

The clam-fishing was unsatisfactory. The mollusks seemed to be about exhausted. Sipes and Saunders worked faithfully for several days, but only found a dozen or so, and none of them contained pearls.

“We gotta wait fer a new crop,” declared Saunders, who was disgusted with the whole trip and wanted to go home.

Bascom persuaded the old sailors to remain a few days, to give the Ancient a chance to come back, and to impress the Captain at the village with the idea that he was in no hurry to see him. They had no love for that red-nosed worthy and acquiesced.

The flatboat was restored to its berth on the bank, and in the early morning Sipes and Saunders made a trip to the village in the Crawfish. On their return at lunch time they reported that they had seen nothing of the Captain.

The Troopers of the Sky(From the Author’s Etching)

I spent the afternoon up the river and heard a great many shots echoing through the woods. When I returned to camp I found that Bascom had been out shooting robins. There were thirty-seven of the innocent little redbreasts in his bloody bag, and the game warden was with him when he returned from his shameful expedition.

It seemed that Sipes, when he arrived from the village, had pictured to Bascom the glories of a certain robin pie, “with little dumplins,” that he said Narcissus had once compounded, and the fascinated onion-skinner, although knowing that it was illegal to kill songsters, had taken the risk of going out with his gun to obtain material for another one. He was mad all the way through, but was a much subdued man.

“Them robins is song birds, an’ it’s ag’in the law to kill ’em at any time,” said the warden. “They’re wuth ten dollars apiece an’ costs to the state, an’ you’ve got to go to the county seat with me. Mebbe you’ll be jugged too, fer they’re pretty severe with fellers that shoot little birds.”

Bascom offered to fix up the matter privately, on a liberal financial basis, but the minion of the law was inexorable. The culprit must have regarded that part of the country as most peculiar and inhospitable.

Erskine Douglas Potts, the game warden, was a lengthy loose-jointed individual. One eye drooped in a peculiar way, and seemed to rove independently of the other. Sipes declared that “Doug’ c’n look up in a tree with one eye, an’ down a hole with the other lamp at the same time.” Odd humor radiated from him and he had a deep sense of his dignity as an upholder of the “revised stat-toots.” Two printed copies of the state game laws protruded from the top of his trousers, where they were secured by a safety pin. “Casey,” his small yellow dog, was his inseparable companion. They were a devoted pair of chums and Potts refused to allow a “pitcher” to be made of him unless the dog was included.

Casey was an animal of rare acumen. He had once taken the prize at a village dog-show, where intelligence and not breeding was considered, and his laurels were regarded as imperishable by his proud master.

“They didn’t put me up, but if they had I’d ’a’ lost out ’side o’ him,” he remarked. “The dogs is the smartest things in that town, an’ they couldn’t be no kind of a brain show thar without ’em. This dog’s a wonder. He knows the time o’ day, an’ all the short cuts through the woods an’ sand-hills. We ain’t neither of us got no pedigrees, but we seem to navigate ’round pretty well without ’em.

“W’en we hear any shoot’n off in the woods we go out on a still-hunt. Casey finds the foot trails an’ follers ’em up. ’Tain’t long ’fore we spot the feller with the gun. Then we foregather with ’im an’ ask fer ’is shoot’n license, an’ inspect wot ’e’s got. If it’s song birds, er game out o’ season, we form in line an’ perceed to whar the scales o’ justice hang, an’ the feller has to loosen up.

“Casey hikes down to the depot w’en they’s anybody that with baggage er packages, an’ sniffs ’em over. If ’e scents any birds ’e alw’ys lets me know. I git half o’ the fines that’s levied, an’ this ’ere bag we’ve jest brought in looks like pretty good pickin’. It’s durn poor shoot’n that don’t shake down sump’n fer somebody. Casey an’ me lives alone, an’ we have lots o’ long talks together. He knows more’n most lawyers. He’s my depity, an’ I couldn’t git along without ’im. A feller that owns a nice new breech loadin’ gun offered to trade me a horse fer ’im last week, but they was nothin’ doin’.

“Me an’ Casey don’t miss much that goes on ’round ’ere. After them robins is took off o’ the bar o’ justice, we’ll fetch ’em back, if the jedge don’t cop ’em, an’ we’ll let yer dark-spot cook ’em, an’ we’ll have a pie that’s all our own. Yer moneyed friend c’n think about it while ’e’s in the county jail countin’ the change ’e’s got left.”

It was arranged that the prisoner and his marble-hearted captor should be taken to the village that night in the Crawfish, and the journey to the county seat made the next day.

The evening meal was far from festive. The boat was poled out into the current and started away down stream in the moonlight, with Saunders at the helm. Sipes and the warden smoked complacently on the roof of the cabin, and the moody Bascom sat between them. Casey was in charge of the evidence near the bow, where he jealously guarded the bag of robins and kept his eye on the evil doer.

Sipes had remarked to me before they left that “things has been pretty dull ’round this ’ere camp, but now they’s sump’n doin’.”

“Ah tole Mr. Bascom that ’e bettah not go shoot’n’ much ’round heah,” said Narcissus, with a quiet chuckle, after the party had left, “but ’e said ’e wanted one o’ them robin pies that Mr. Sipes tole ’im ’bout. Ah don’t remembah ’bout no robin pie, but it might be awful good. The wa’den has ’fiscated all them robins, an’ Ah guess we got to fix up sump’n else fo’ dinnah tomorrow.”

I asked no questions when the old shipmates returned, and they volunteered no information as to any part that they might or might not have played in the little drama of the afternoon, but I suspected that the “third degree” that Sipes had mentioned before we started was now in process of application.

Justice was dealt out to Bascom with unsparing hand when he reached the county seat, and he was compelled to pay the full penalty of his wrongdoing. After liquidating his fines, and incidentally himself, in a moderate way, to drown his troubles, he had spent an hour or so about town, and was just taking the train, when he was again arrested for carrying a concealed weapon. He had neglected to leave his revolver at the camp, and was assessed accordingly.

He came back to us after three days, with a crestfallen air, and said that he was ready to break camp if we were. Nothing had been seen of the Ancient or the Captain, and he regarded it as poor strategy to stay longer, with no particular excuse for doing so. He would devise some other way of getting at the coy landowners.

We packed up our things and departed. The engine stopped just before we reached the village, and we found that our gasoline was exhausted. Unfortunately the oars had been forgotten when we left Shipmates’ Rest, but as the new motor had worked perfectly, there had been no occasion for them. We poled the Crawfish to the old pier, landed, and stowed my little boat and tent where we had found them. We then took the gasoline can and walked up to the village, leaving Bascom in charge of the Crawfish.

He was anxious for us to run across the Captain accidentally, and if possible get him down to the boat on some pretence. In effect, we were to shoo the wary Captain to the ambush, where the onion-skinner lay in wait with his tempting yellowbacks. We did not look very hard for him, but I happened to see him down the road talking to a man in a buggy. I was not inclined to do any shooing, and did not disturb him.

We spent some time in the village store. When we came out, the sky, which had looked threatening all the morning, was overcast with dark angry clouds. A big storm was brewing, and we decided not to start for Shipmates’ Rest until it was over. There was a high off-shore wind. The waves were rising rapidly out on the lake, but the protected water along the bluffs was still comparatively calm. As the wind increased we went down to the pier, intending to tie the boat up in a more sheltered place, and remain at the village all night. We found to our dismay that the Crawfish was adrift far out on the water. Under the strain of the wind and the river current, the line had parted that had held it to the pier.

Bascom was gesticulating wildly for help, but there was no means of getting to him. There happened to be no boats around the mouth of the river large enough to be of use in the waves that were now breaking over the Crawfish. There was no gasoline on the boat, and if there had been oars Bascom could not have got the boat back with them after he got into the current. Evidently he had not realized his danger until it was too late to jump overboard and swim ashore, or it may not have occurred to him.

“That poor feller ain’t got no more chance ’an a fish worm on a red-hot stove,” shouted Sipes above the roar of the wind, as we watched the helpless craft being tossed and borne away. To do the old man justice, he forgot the boat, and our belongings on it, in the face of Bascom’s peril, as we all did.

There was a faint hope that some steamer on the lake might rescue him, but there was none in sight, and we doubted if the boat would stay afloat more than a few minutes more in such a wind and sea. Rain began to come in torrents, and the distant object, that we had watched so anxiously, was obliterated by the storm.

We made our way back to the village store with difficulty, and telephoned to the lifesaving station about thirty miles away on the coast, but there was no possible hope of help from there. There was much excitement among a few villagers who came out into the storm, but nobody could suggest any means of relief.

We spent a gloomy and sleepless night in the little town, where we were hospitably provided for.

Somewhere far out on the wind-lashed lake the turbulent seas and the storm played with a thing that had become a part of the waste and débris of the wide waters. Bascom’s god was in his leather wallet, but it was powerless, except with men. The winds and the waves knew it not. Greed, that dominates the greater part of mankind, becomes ghastly illusion, as the frail creature it disfigures blends into the elements when finality comes.

Mother Nature, with her invincible forces, sometimes chastens her erring children who do not understand. She had guarded her treasures in Duneland through the countless years, and now, with a breath from the skies, a destroyer had been wafted from its portals.

Poor Bascom had indeed received the “third degree” and had been “exported” in a way that was not contemplated by the sorrowful old sailors.

The storm subsided the next day and we made the journey along the beach on foot to Shipmates’ Rest, where we found everything in good order. We related our doleful experience to John, and there was a cloud over our little party for several days. Like most of the troubles in this world, particularly when they are those of others, the sadness of Bascom’s fate soon lost its poignancy.

“I’m sorry fer Bascom,” remarked Sipes, “an’ I hate to lose the boat an’ all the stuff wot’s on it, but Gosh, I wish I had that wad! He made a lot o’ money in ’is business, an’ money’s all ’e ever wanted to git, an’ ’e’s got plenty of it right with ’im, so he ain’t got no kick comin’. He was a hard citizen. All they was that was good about ’im was ’is cash-money, an’ it’s like that with a lot o’ people. I don’t s’pose ’e’ll ever git anywheres near the New Jerus’lum that Zeke tells about, but if ’e does, I bet ’e’ll want to skin some o’ them pearls wot’s on the gate.”

I arranged to leave for home, and promised to write to Sipes if I ever saw anything in the newspapers relating to the finding of Bascom’s body.

“By the way, Sipes, I never knew your first name. What is it?”

“My fust name? It’s Willie, but don’t you never put that on no letter. Me an’ you an’ Bill’s the only ones wot knows it.”

I departed out of Duneland, and one cold afternoon during the winter I opened the door of my city studio, after a short absence, and under it was a card that had been left during the past hour. On it was engraved, HORATIUS T. BASCOM

REAL ESTATE

FARM LANDS AND MANUFACTURING

SITES A SPECIALTY

I mailed it to “Mr. W. Sipes” with a trite allusion to bad pennies, and such other comment as seemed befitting.