THE RESURRECTION OF BILL SAUNDERS

By Earl Howell Reed

Bill Saunders

SIPES and Saunders had acquired a detachable motor for their boat. Catfish John had obtained it on one of his various trips to the little village at the mouth of the river about fifteen miles away. The disgusted owner had traded it in on his fish account with John, and had thrown in, as a bonus, some gasoline, mixing oil, a lot of damaged small tools, a much-worn book of instructions, and a great deal of conversation. He was careful to impress on John that he wanted no “come back,” and was not responsible in any way for what the contraption might or might not do after it left him. He had just had it “overhauled” by the makers for the third time, and he never wanted to see it again.

John, knowing the great persistence and ingenuity of his friends, and feeling that he was in the way of doing them a favor, put the despised machine in his wagon and departed.

The following morning he drove up the beach to the fish shanty for his supplies.

“Wot’s all this iron fickits?” asked Sipes, as he peered curiously into the wagon.

“That’s a gas motor wot ye stick on the back o’ yer boat. You fill up the tin thing with gasoline an’ some kind of oil, an’ then whirl that wheel wot’s got the little wooden handle on it, an’ ’way she goes an’ runs yer boat, an’ ye don’t ’ave to row, an’ ye c’n go anywheres whar it’s wet. I traded wot a feller owed me fer ’bout fifty pounds o’ fish fer it, an’ if you fellers want it, ye c’n ’ave it if ye gimme the fish.”

“Bill, come ’ere!” yelled Sipes.

The tousled gray head of Bill Saunders appeared in the doorway of the shanty.

“Wot’s doin’?” he asked sleepily.

“Never you mind; you put on yer trowsies an’ come on out ’ere an’ see wot our ol’ friend an’ feller-citizen ’as fetched in.”

Without following Sipes’s instructions implicitly, the disturbed occupant of the shanty came out to the wagon.

“This ’ere little book wot the feller gave me,” continued John, “has got it all in, with pitchers of all the little things in the machine, an’ how to grease it, an’ run it, an’ ev’rythin’ about it. Thar’s a lot o’ figgers in it wot tells wot ye pay fer all the things that gits busted.”

On the cover of the worn book, which the old man produced, was a highly colored picture of a slender youth, gay and debonair, with one of the machines in a canvas carrying bag. He swung it lightly and merrily in his hand as he tripped along toward his boat, which floated in the distance, where soft ripples laved its polished sides with pink water. His derby hat was tilted to a careless angle. On his face was a smile of joyful anticipation. There was no more suggestion of exertion than if the bag contained toy balloons instead of a motor. Nevertheless it required the united efforts of the three weather-buffeted old fishermen to get the machine out of the wagon on to the beach. Such is the contrast between exuberant youth and seasoned maturity.

“I bet that feller with the hard-boiled hat ain’t got the machine in that bag at all,” remarked Saunders, as he studied the scene on the cover. “They’s prob’ly some fellers follerin’ ’im with it that don’t show in the pitcher. I don’t like that cigarette moustache on ’im; I’ll bet ’e knows durned little ’bout navigation ’ceptin’ with crackers on soup. You leave this thing ’ere an’ me an’ Sipes’ll try ’er out, an’ if it works, we’ll keep ’er. Anyhow we’ll make up the fish yer out an’ you won’t lose nothin’.”

The fish for John’s peddling trip were carefully sorted out and recorded by Sipes, with a stubby pencil, on the inside of the shanty door where the accounts were kept. The nets had been lifted in the early morning and the supply was abundant. When John had sold the fish the proceeds were to be divided equally.

After John and his aged horse “Napoleon” had left with the slimy merchandise, the old shipmates sat down and considered the apparatus.

To this primitive coast, torn by the storms and yellowed by the suns of thousands of years, where elemental forces had ruled since the beginning, had come a strange and misfitting thing. It seemed an unhallowed and discordant intrusion into the Great Harmonies. Somehow we can, in a measure, be reconciled, poetically, to the use of steam, without great violence to our worship of the grandeur of nature’s forces, but there is no poetry in a gasoline engine. It is a fiend that wars upon things spiritual. Its dissonant soul-offending clatter on the rivers that flow gently through venerable woods, and out in the solitudes of wide and quiet waters is profanation.

Utilitarianism and ideality clashed when the motor touched the beach, but these things did not disturb Sipes and Saunders, engaged in the contemplation of the machine, as bewildered savages might gaze upon a fragment of a meteor that had dropped out of the sky from another world.

After a while they lugged it to the shanty. “I could ’a’ carried it alone if I’d ’a’ had one o’ them darby hats on!” declared Sipes.

They spent long hours over the book of instructions, and the light in the shanty burned far into the night. They carefully and repeatedly examined the various parts in connection with the text. There were some words which they did not understand, but they finally felt that they had mastered the problem.

Saunders remarked, as they turned into their bunks, “I guess we got ’er, Sipes. We’ll pour in the juice an’ start ’er up in the mornin’. Then we’ll buzz off on the lake an’ look at the nets.”

“She oughta have a name on ’er, like a boat,” suggested Sipes. “S’pose we call ’er the ‘Anabel,’ er sump’n like that?”

“‘Anabel’ ain’t no kind of a name fer anythin’ o’ this kind. I seen that name on a sailboat once’t that didn’t make no noise at all, an’ this thing will. Wot’s the matter with ‘June Bug’?”

“All right,” said Sipes, “‘June Bug’ she is, now let’s go to sleep.”

Loud snores resounded in the shanty, and the “June Bug” spent the night on the floor near the stove. Fortunately there was no leak in the gasoline tank or fire in the stove.

With the coming of dawn the old cronies hastily prepared breakfast. The lake was calm and everything seemed propitious for the initial voyage with the June Bug. That deceptive bit of machinery was carefully carried to the big flat-bottomed boat, and, after an hour of hard work, was securely attached to the wide stem. The gasoline tank was filled to the top, the batteries adjusted, the spark tested, and every detail seemed to tally with the directions. Sipes gave the fly-wheel a couple of quick turns. The motor responded instantly. The propeller ran in the air with a cheerful hum, and the regular detonations of the little engine awoke the echoes along the shore.

With shouts of boyish glee the old shipmates pushed the big boat over the rollers on the sand and down into the water. There was much discussion as to which should run the engine and steer. Sipes produced a penny and, by flipping it skilfully, won the decision.

“I don’t s’pose they’s any use takin’ the oars, but I’ll put ’em in,” he observed as he threw them into the boat.

Saunders complacently took his place forward. Sipes gave the boat a final shove and jumped in. He pushed it well out with one of the oars, and turned and looked with pride on the wonderful labor-saving device on the stern. It seemed too good to be true.

“Say, Bill, to think that us fellers c’n go hundreds o’ miles out’n the lake, if we want to, an’ ev’rywhere else, an’ let this dingus do all the work. We c’n set an’ smoke an’ watch the foam, an’ listen to the hummin’ o’ the Bug. I’ve heard fellers go by way out b’yond the nets with them choo-choo boats, but I never seen wot did it before. Gosh! but this is fine. Now all we gotta do is to touch ’er off an’ away we go!”

The old man’s single eye beamed with enthusiasm, as he grasped the handle and made the prescribed turns. The result was a couple of pops and some coughing sounds somewhere in the concealed iron recesses.

“Guess she’s coy, an’ I didn’t give ’er enough. I’ll whirl ’er some more.” His efforts were again ineffectual.

“Lemme try ’er,” pleaded Saunders.

“Not on yer life! You keep off. You don’t know nothin’ ’bout machines. She’ll be all right in a minute. Gimme that book!”

The boat drifted sideways for some time while Sipes studied the directions and puttered over the parts with various tools.

“I’ll jolly ’er up with the screw-driver an’ monkey-wrench, an’ she’ll feel better.” He tinkered and cranked for nearly an hour, during which time Saunders offered many ill-received suggestions. Then came a torrent of invective.

“You got too many whiskers to swear like that,” remarked Saunders, “you’ll burn ’em.”

“Never you mind, I’m watchin’ ’em! The man wot ’ud make a thing like this, an’ take good cash money fer it, er even fish, oughta be cut up an’ sizzled!” he declared. “The skin’s all offen my hands, an’ I wish the devil wot built this gas bug ’ud ’ave to keep ’is head in hot tar ’til she went. Come ’ere, Bill, an’ start ’er up. You seem to know so much about it.”

They exchanged places and Sipes glared maliciously at the rebellious motor from the bow. Saunders put his pipe in his pocket, produced a chunk of “plug twist,” and bit off a large piece. He stowed it comfortably and considered the problem before him. After a couple of hours of fruitless efforts the profanity in the boat became unified and vociferous. The ancestors of the makers of the motor, and those of the man who had it last, as well as the undoubted destiny of everybody who had ever had any connection with it, were embraced in sulphuric execration. John was, in a way, excepted. He “meant well,” but he was “a damned old fool.”

After this general vituperation the old sailors rested for a while and rowed back. The constant cranking had turned the propeller a great many times. The boat had made erratic headway and was quite a distance from shore. They landed, pulled the boat out on the sand with the windlass, and retired to the shanty for lunch and consultation.

Saunders strolled out a little later, with a piece of cold fried fish in his hand, and looked the motor over again. He gave the fly-wheel a careless turn and the engine started off gayly. Sipes heard the welcome sound and ran out, spilling his coffee over the door step. Lunch was discontinued, and the boat was re-floated. There was more cranking, but no answering vibrations. With more profanity the craft was restored to its berth on the sand, and another retreat made to the shanty.

“The Bug’ll run all right on land,” declared Sipes, “an’ we’ll turn the propeller so’s the edges’ll be fore an’ aft, an’ belay it. We’ll bend a rim on it an’ fasten some little truck wheels on the bottom o’ the boat. Then we’ll run the ol’ girl up an’ down on the hard sand ’long the edge o’ the water. We won’t go in the lake at all ’til we git ’er well het up, an’ then we’ll turn ’er in sudden an’ cut them lashin’s. She won’t know she’s in an’ ’way she’ll go.”

For many days the old shipmates struggled with the obstinate mechanism. It once ran for an hour without a break and they were jubilant. “Some gas bug that!” Saunders exclaimed joyfully, but just then it sputtered and stopped. They were quite a ways out, and the oars had been forgotten. Fortunately there was a light in-shore breeze and they drifted to the beach about two miles from home.

The oars were finally procured and the day closed with everything snug and tight at the shanty.

“I bet we ain’t got the right kind o’ gasoline,” declared Sipes. “They’s lots o’ kinds. This ’ere wot’s in the Bug ain’t got no kick to it. We got too much oil mixed in it, an’ we gotta git s’more.”

When John came again the many troubles were related to him. He knew nothing of motors, but offered to get some more gasoline when he went to the village, and to bring the former owner of the motor over to see if he could suggest anything.

“You jest fetch that feller,” said Sipes, “an’ we’ll take ’im out fer a nice little spin on the lake, an’ we’ll go where it’s deep.”

When the new gasoline came there was much more tinkering and study of the directions. Resignation alternated with hope. Sometimes the motor would run, but more often it refused. John finally took it to the village and it was shipped to the makers. A carefully and painfully composed letter was put in the “pustoffice.” The long-delayed answer was that the machine needed “overhauling,” which would cost about half as much as a new one.

“The money that them pie-biters makes ain’t sellin’ motors, but overhaulin’ ’em,” declared Sipes. They sell one o’ them bum things an’ git their hooks in an’ git a stiddy income from it long as you’ll stand fer it.”

It was decided, after much discussion, to send the money “fer the overhaulin’.” Several months elapsed. The machine came back too late to be of further use that season, and was carefully stowed away for the winter.

“She’ll prob’ly need another ‘overhaulin’’ in the spring ’fore she’ll go, an’ them fellers’ll want to nick us ag’in an’ keep ’er all next summer,” said Saunders. “If they charged by the days they kep’ ’er instid o’ by the job, we’d be busted. They’ll bust us anyhow, an’ it might as well be all at one crack. The Bug’s goin’ to stay in the house now, where she won’t git wet. She ain’t goin’ out on the vasty deep no more ’til spring. If she gits uneasy, she c’n run ’round in ’ere.”

The following May I called at the shanty and found Sipes sitting disconsolately in the door-way. After visiting with him for a while, I inquired for Saunders.

“Poor Bill’s dead. I ain’t got no partner now an’ it’s awful lonesome. He was a nice ol’ feller. He fussed ’round with the gas bug fer days an’ days, an’ ’e couldn’t make it go. He come in one night late, an’ the next mornin’ ’e didn’t git up. He didn’t seem in ’is right mind. His hand ’ud keep goin’ ’round an’ ’round, like it was crankin’ sump’n. Then ’e’d make sputterin’ sounds with ’is mouth like as if a motor was goin’, an’ then ’e’d keep still a long time like the Bug does, an’ then begin ag’in. He wouldn’t eat nothin’, an’ one night he said ’e guessed ’e needed overhaulin’. Then ’e said ‘choo-choo! choo-choo!’ three er four times, an’ ’e was gone. Come on with me an’ I’ll show you where ’e was laid away.”

We walked along the shore a short distance, crossed the beach and climbed the bluff. Near the foot of an old pine was a mound, on which was scattered the dried remnants of many spring flowers, which probably had come from the low ground in the ravine. Several bunches of white trilliums, with their leaves and roots, had been transplanted to the mound, but they had withered and died. A wide board, which protruded from the ground at the head of the grave, bore the rude inscription:BiLL SauNDERS—DEADUnder the name was a rough drawing of the fly-wheel of the motor, evidently made with Sipes’s stubby pencil.

Chiselled epitaphs on granite tombs have said, but told no more.

We stood for some time before the mound. The old sailor wiped a tear from his single eye as we left Bill’s last resting place in silence and sorrow.

“Him an’ me was shipmates,” said the old man sadly, as we returned to the shanty. “I off’n go up there an’ set down an’ think about ’im. Bill was honest. They’s lots o’ fellers that wouldn’t swipe nothin’ that was red-hot an’ nailed down, ’spesh’ly ’round ’ere, but Bill never’d touch nothin’ that didn’t b’long to him er me. It was the gas bug that killed ’im. Fust it made ’im daffy an’ then it finished ’im. She’s over there now on the stern o’ the boat. I ain’t never had ’er out this year, but I’m goin’ to try ’er once’t, jest fer Bill’s sake. I think ’e’d like to have me do it.”

After many condolences, and a general review of the Bug’s disgraceful career by Sipes, I picked up my sketching outfit and resumed my journey, depressed, as we all are, by a sense of the transience and unsolvable mystery of life, when we have stood near one who has gone.

One calm morning, about a month later, I was rowing on the lake several miles from Sipes’s shanty. A boat appeared in the distance. Its high sides, broad beam, the labored, intermittent coughing of a motor, and the doughty little bewhiskered figure on the stern seat were unmistakable. Sipes altered his course slightly so as to pass within fifty or sixty yards. I wondered why he did not come nearer. He went on by with a cheery “Wot Oh!” and a friendly wave of his hand. Evidently he was on some errand that he did not want to explain, or was afraid to stop the motor, fearing that it would not start again. In a few weeks I encountered him again, under almost identical conditions. His nets were nowhere in the vicinity.

In the early fall I found an old flat-roofed hut, built with faced logs, about six miles down the coast, in the direction that the old man had been going when I had last seen him. It was in a hollow near the top of a high bluff that faced the lake. It was effectually hidden from the water and shore by a bank of sand and tangled growth along the edge of the bluff. Built against the outside was a large dilapidated brick chimney, entirely out of proportion in size to the cabin. No smoke issued from it and the place seemed deserted. I went down to the beach. A mile or so further on I found a fisherman repairing a boat on the sand, and asked him about the cabin.

“That place is witched,” he declared. “Thar’s funny doin’s ’round thar at night an’ don’t you go near it. Thar’s a white thing that dances on the roof. It goes up an’ down an’ out o’ sight, an’ then thar’s a big thunderin’ noise. I don’t want to know no more ’bout it’n I know now. It don’t look right to me. I seen a wild man ’round ’ere in the woods once’t, a couple o’ years ago, an’ mebbe he lived thar an’ ’e’s dead an’ ’e hants that place. I don’t come ’round ’ere often an’ I don’t want to.”

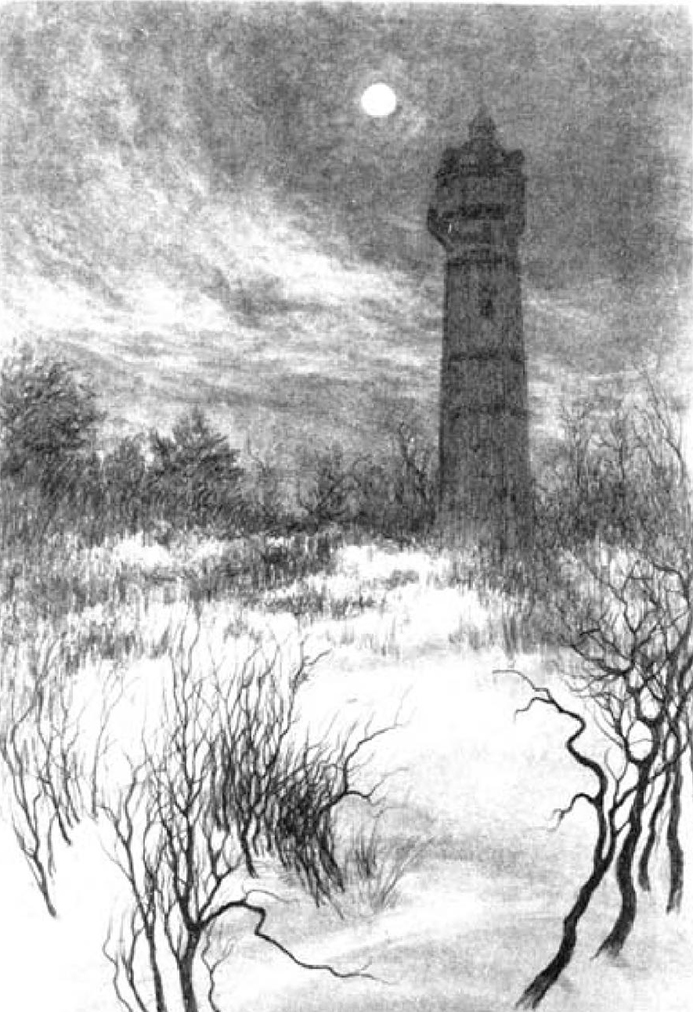

THE “BOGIE HOUSE”(From the Author’s Etching)

My curiosity was aroused and I decided to investigate the mystery when an opportunity came. About nine o’clock one night I walked up a little trail in the sand that led toward the cabin from the woods back of the bluff. There was a dim light inside that was extinguished when I carelessly stepped on a mass of dead brush that had been piled across the path. The breaking of the little sticks had made quite a noise. Immediately a long, wavy, white object appeared over the roof of the cabin. It vaguely resembled a human shape and looked peculiarly uncanny. It swayed back and forth a few times and then seemed to grow taller. The trees beyond were partially visible through it in the uncertain light. Clearly I was in the presence of a spook. The apparition vanished as suddenly as it came. Then a dull, hollow sound came from the cabin, followed by a low, rasping, ringing noise. When it ceased, the silence was weird and oppressive.

I went on by the structure to the edge of the bluff, where another pile of dry brush obstructed the path, and purposely walked on it, instead of over the high sand on the sides of the opening. The breaking sticks made more noise. I turned and again saw the spectral form over the roof. The wraith swayed slowly to the right and left, bent backward and forward a few times, grew longer and shorter, and disappeared as before.

In departing I stumbled over a board which stuck out of the sand, and in the dim light could distinguish the words “Dinnymite—Keep Out!” heavily scrawled on it with red paint.

Evidently visitors were not wanted, and the tell-tale brush-piles were designed to give alarm of the approach of intruders. The functions of the filmy ghost and the queer sounds were to inspire terror of the place.

I related my experience to Sipes the next time I saw him. He was deeply interested.

“Did ye hear any groanin’ after them funny sounds?” he asked, with a quizzical look in his eye. I replied that I had not.

“I’ll tell ye wot we’ll do,” said he, after a few moments of reflection, “you an’ me’ll go down to that bogie house some time an’ we’ll butt in an’ see wot’s doin’. I gotta go that way in the boat next week. We’ll take the gun, an’ mebbe we’ll blow that bogie offen the top o’ the house. I seen that place last year an’ I know where it is.”

I did not approve of the idea of needlessly invading the privacy of anybody who did not want to see us, and who had inhospitably stocked their domain with brush-piles, ghosts, and forbidding placards, but there was a strange look in Sipes’s eye that convinced me that the trip might in some way be justified.

On the appointed day we made the start. “I always spend jest an hour tunin’ up the Bug,” remarked the old man, as he began cranking the motor, “an’ then if she don’t pop, I cuss ’er out fer jest fifteen minutes, an’ then I row. Hell, I gotta have some system!”

Fortunately the Bug was in good humor and took us three-quarters of the distance without a break. It then went to sleep, and half an hour’s cranking and assiduous doctoring failed to arouse it.

“I got a great scheme,” said Sipes. “W’en she gits like that I fasten the steerin’ gear solid fer the way I want to go, an’ then w’en I keep on crankin’, the propeller goes ’round an’ ’round, an’ I keep goin’ some.”

A little later a single turn of the fly-wheel started the treacherous device, but it was going backward. Sipes promptly seized the oars and turned the stern of the boat toward our destination.

“We got ’er now! Jest keep quiet an’ touch wood! Sometimes she likes to do that, an’ if I try to reverse ’er she’ll balk. She thinks it’s time to go home, but it ain’t. This crawfish navigat’n’s fine w’en ye git used to it.”

We landed beyond a point on the beach which was opposite to the cabin. After we had secured the boat to some heavy drift-wood with a long rope, I followed Sipes up the side of a bluff west of the cabin. We made a detour through the woods and approached it at dusk. The dry brush-piles practically surrounded it at a distance of about fifty yards.

“Don’t step on none o’ them sticks,” cautioned Sipes. He gave a low, peculiar whistle, which was answered from the cabin. “That there’s the high sign,” he remarked, as we walked to the door. We were greeted by Bill Saunders, alive and in the flesh. He seemed surprised that Sipes had brought a visitor, but was very cordial. Sipes greatly enjoyed the situation and chuckled over what he considered an immense joke.

“You see it’s like this,” he explained. “Bill got to thinkin’ wot’s the use o’ gasoline? W’y not have sump’n that ’ud run ferever, an’ not ’ave to keep buyin’ that stuff all the time? He’d set an’ think about it in the shanty an’ then somebody’d butt in an’ mess up ’is thinkin’. He’d go ’way off an’ set on the sand by ’isself, an’ then some geezer’d come snoopin’ ’long an’ chin ’im, an’ ’e couldn’t git no thinkin’ done.

“That cusséd dog o’ Cal’s come ’long the beach one mornin’. He’s bin runnin’ wild since Cal lit out. Fer years this whole country’s been fussed up with ’im an’ ’is doin’s. He died jest as ’e was pass’n the shanty. We buried ’im up there on that bluff, an’ that gave Bill an’ me an idea. We fixed up the place so’s people ’ud think Bill ’ad faded. Then we humped off down to this bogie house so Bill could ’ave some peace an’ quiet to do ’is thinkin’ in. Bill’s invent’n some kind o’ power that’ll make ev’rythin’ hum w’en ’e gits it finished. It’ll put all them other kinds o’ machines on the blink. That cusséd motor’ll go ’round an’ ’round, an’ she can’t stop ev’ry time ye bat yer eye at ’er.

“I been bringin’ things down ’ere fer Bill to eat, an’ sometimes little beasties come ’round the hut wot ’e shoots. We fixed up that dry brush so’s nobody ’ud come snoopin’ ’round without Bill knowin’ it. Him an’ me’s goin’ to divide wot we make out o’ th’ invention, an’ we’ll ’ave cash money to burn w’en ’e gits it goin’. We’ll set in a float’n palace out’n the lake an’ smoke seegars, with bands on ’em, an’ let the other fellers do the fishin’, won’t we, Bill?”

“You bet!” responded Saunders. Just then we heard a sound of breaking sticks outside. Instantly he seized a long pole that lay along the side of the wall. It was fitted with a cross-piece and a round top. Over it was draped various kinds of thin white fabric. He mounted a box and pushed the contrivance up through a hole in the flat roof, moved it up and down, waved the upper end back and forth a few times, and withdrew it. He thumped the empty box heavily with the end of the pole as he took it in, and picked up about four feet of rusty chain, which he shook and dragged over the edge of the box several times.

Through a small chink between the logs we saw a dim figure moving rapidly away in the gloom. We heard the crackling of the brush at the edge of the bluff, and knew that the intruder had gone.

“That feller’s got the third degree all right,” remarked Saunders, as he carefully put the ghost back into its place. “’Tain’t often anybody comes, but w’en they do they gotta be foiled off. Them dinnymite signs helps in the daytime, but fer night we gotta have sump’n else.

“This dress’n’ on the ghost mast come from Elvirey Smetters. We made up with ’er after ’er wedd’n with Cal busted up an’ Cal skipped. She was wearin’ most o’ this tackle fer the wedd’n, an’ she said she didn’t never want to see it ag’in. There’s a big thin veil fer the top o’ the pole, an’ some o’ the other stuff she said was long-cherry, er sump’n like that. We keep that hatch battened down w’en it rains, but she’s loose most o’ the time. W’en I shove the ghost out it pushes it open.”

Saunders extracted some rye bread, salt pork, and cheese from a cupboard. We fried the pork in a skillet over some embers in the big brick fire-place, and toasted the cheese. After our simple meal the old man piled more wood on the fire, and we smoked and talked until quite late.

The mechanism, on which Saunders was spending his days of seclusion, reposed under some tattered canvas near the wall. He was reticent concerning it, but Sipes volunteered the information that “they was some little wood’n balls wot went up an’ down in some tubes that was filled with oil, an’ then they rolled ’round inside of a wheel an’ come back.”

“Now you shut up!” commanded Saunders. “You leave this thing to me ’til I git it done, an’ then you c’n talk ’til yer hat’s wore out. They ain’t no use talkin’ ’til we git somew’eres, an’ then we won’t ’ave to talk. Wait ’til I git some little springs that’ll spread out quick an’ come back slow, an’ we’ll be through.”

Saunders’s mind was struggling with the eternal and alluring problem of perpetual motion. He was groping blindly for the priceless jewel that would revolutionize the world of mechanics.

It was after midnight when we bade him good-by, and departed through the moonlit woods for the beach.

We left the old man in the company of his fire, and is there greater companionship? It is in our fires that we find the realm of reverie. The fecund world of fancy reveals its fair fields and rose-tinted clouds in the vistas of shimmering light. Memory brings forth pages that the years have blurred. Fleeting filaments of faces wondrous fair, that long ago faded into the mists, smile wistfully, in halos of tremulous hues, and vanish. Slow-moving figures, crowned with wreaths of gray, sometimes linger, turn with looks of tender mother love, and dissolve in the curling smoke. The years that have slumbered in the old logs come forth at the touch of a familiar wand, and a soft light illumines chambers that time has sealed. The grim realities are lost in the glow of our hearth. In the dreamland of the fire we may ride noble steeds and soar on tireless pinions. We see heroes fight and fall. Cities with gilded walls and bright towers, broad landscapes, enthralling beauty, leaves of laurel on triumphant brows, majestic pageants, and acclaiming multitudes, are pictured in the flickering flames.

On the little stage under the arch of the fireplace the puppets come and go,—the comedies and the tragedies, the laughter and the sorrow. The dramas of hopes and fears are enacted in shifting pantomimes that melt away into the gloom.

Our hearth-stones are the symbols of home. We go forth to battle when their sanctity is imperilled. It would be a desolate world without our fires. Winding highways lead through them on which he who travels must mark the light and not the ruin. He must feel the glow and not the burning, and be far beyond the ashes when they come.

In the twilight, when our lives become gray, and only the embers lie before us, we can still dream, if our souls are strong. If we have learned to live with the ideals we have created, instead of charred hopes, golden visions may linger in the mellow light. Happy hours, as transient as the fitful flames, may dance again, and shine among the smouldering coals.

The grizzled old sailor, who had been fortune’s toy, and had been cast aside, may have found his solace in the visions before his fire. The pictures in it may have been of millions of wheels turned with the new force, myriads of aëroplanes soaring through the skies, dynamos of inexhaustible power giving heat and light, and countless looms spinning the fabrics of the world.

He may have seen himself worshipped, not for his achievement, but for his wealth, in the domain of Vulgaria, where Avarice is king—where worth is measured by dollars—where utter selfishness rules, and the cave man still dwells, veneered with a gilded tinsel of what, in his foolish pride, he thinks is civilization—where vanity parades in the guise of charity—where cruelty and greed hide under fine raiment—where human hyenas rend the weak and grovel before the strong—where the bestiality of the Hun darkens the world—where the only god is Gold, and where the idealist must fight or perish.

One night during the following spring I passed the cabin. The little structure, from which a great light might have radiated over the scientific world, was deserted. A pale, ghostly gleam was visible through the empty window frame. It might have been a phosphorescent glow from one of the decaying wall-logs, or a faint spark from the dream-fire that ever burns in the hearts of men.