The Man Who Did Not Go to Heaven

on Tuesday

by Ellis Parker Butler

The Man Who Did Not Go to Heaven on Tuesday was published in The Century Magazine, July, 1913.

UNCLE NOAH PRUTT, sitting in the front row of seats, leaned forward and put his hand behind his ear, vainly seeking to hear what his wife was saying to Judge Murphy. From time to time he stood up, trying to hear the better, but each time the lanky policeman pushed him back into his seat.

“Judge, yer Honor,” said the policeman, after the fifth time, “this man here has nawthin’ t’ do with th’ case, an’ he’s disthurbin’ th’ coort. Shall I thrun him out?”

“Let him be, Flaherty, let him be!” said the justice, carelessly, and at the words Uncle Noah arose and came forward to the black walnut bar that separated the raised platform of the justice from the rest of the room.

“Ah pleads not guilty, Judge!” said Uncle Noah, laying one trembling hand on the rail and pushing forward his ear with the other. He was a coal black Negro, with close-kinked white hair that looked like a white wig. His nose was large and flattened against his face, and his eyeballs were streaked with brown veins that gave him a dissipated look. He was the type of Negro that, at fifty, claims eighty years of age, and, so judged, Uncle Noah Prutt might have been anywhere between sixty and one hundred and ten. As he stood at the bar his black face bore a look of the most deeply pained resentment, and his thick lower lip protruded loosely as a sign of woe.

“Sit down!” shouted both the justice of the peace and the policeman, and, with his lip hanging still lower, Uncle Noah backed into his seat. He sat as far forward as he could, and leaned his head still farther forward.

“Who is that man?” asked the justice of no one in particular.

“Him? He’s mah husban’,” said the young colored woman, with a slight up-tilt of her nose. “Yo’ don’ need to pay no ’tention to him at all, Jedge. Ah ain’ ask him to come yere. He ain’ yere in no capacity but audjeence, he ain’.”

“He has no connection with this case?” asked the justice.

“No, sah!” said the young woman, decidedly.

“If he makes any more trouble, Flaherty,” said the justice, “put him out of the court. Now, what is this trouble, Sally?”

The young woman standing against the bar was fit to be classed as a beauty. Well-formed, with a rich yellow skin through which the blood glowed in her cheeks, with masses of black hair and her head carried high, she was superb, even in her cheap print wrapper. Even the fact that her feet were hideous in a pair of broken and run-down shoes of the sort worn by men did not impair her general appearance of an injured brown Venus seeking justice, and when she glanced at the prisoner her bosom heaved with anger and her brown eyes glowed dangerously.

The prisoner sat humped down in a chair in an attitude of the most profound dejection. He was of a darker brown than the woman, and so loose of joint that when he moved he flopped. His feet were so large as to be almost grotesque, and he was so thin that the bones of his shoulders were outlined by his light coat. But as he sat in the prisoner’s seat his face was the most noticeable feature. It was thin and long for a Negro, but with such high and prominent cheek-bones that his eyes seemed hidden in deep caves, and the eyes were like those of a dog that knows he is to be beaten. His wide mouth hung far down at the corners. He was a picture of the utterly crushed, the utterly helpless, the utterly hopeless. He was the shiftless Negro, with the last ray of hope extinguished. He had but one thing to look forward to, and that was the worst. As the justice asked Sally the question the prisoner’s mouth sagged a bit farther at the ends, and his eyes took a still sadder dullness.

“Yo’ ain’ miss it none when yo’ asks whut am dis trouble, Jedge,” said Sally, angrily. “Dis yere ain’ nuttin’ but trouble, an’ I gwine ask yo’ to send dis yere Silas to jail forebber an’ ebber. Yassah! An’ den he ain’ gwine be in jail long enough to suit me. An’ Ah gwine ask yo’ to declare damages ag’inst him, fo’ huhtin’ mah feelin’s, an’ fo’ tryin’ to drown me, an’ fo’ abductin’ me away from dat poor ol’ no-’count Noah whut am mah husban’, an’ fo’ alieamatin’ mah affections, on’y he couldn’t. When Ah whack him awn de head wid dat bed-slat—”

“Now, one minute,” said the justice, raising his hand. “Flaherty, what do you know about this case?”

“Well, yer Honor,” said the policeman, in the confidential tone an officer of the law assumes when he feels that he, and he only, can explain matters, “th’ way ut was was this way: I was walkin’ me beat up there awn Twilf’ Strate this mawrnin’, like I always does, whin I heard a yellin’ an’ a shoutin’. So I run into th’ lot—”

“What lot?” asked Justice Murphy.

“’Twas betwane Olive an’ Beech Strates, yer Honor. This here deff man, Noah Prutt, lives in a shack-like there, facin’ awn th’ strate. Th’ vacant lot is full iv thim hazel-brushes an’ what all I dunno.”

“You said there was a shanty on the lot. How could it be a vacant lot if there was a shanty on it?” asked the justice.

“Now, yer Honor,” said Flaherty, with an ingratiating smile, “there’s moore than wan lot in th’ wurrld, ain’t there? Th’ lot this Noah Prutt lives awn is wan iv thim. And th’ nixt wan is another iv thim. An’ th’ nixt wan t’ that is th’ third iv thim, an’ th’ ould Darky owns all iv thim, and iv th’ three iv thim but wan is vacant, and that’s th’ middle wan. There’s a shanty awn th’ furrst wan, and there’s a shanty awn th’ thurrd wan, an’ as I was sayin’, there’s nawthin’ awn th’ vacant wan excipt brush-like, an’ mebby a few trees, an’ some tin cans, an’ whatnot.”

“Very good!” said his honor. “Go ahead.”

“Well, sor,” said Flaherty, “this Prutt an’ this wife iv his lives in th’ furrst shanty, but th’ other wan is vacant excipt whin ’t is occupied. Th’ ould man rints ut now an’ again, an’ a dang lonely habitation ut is, set ’way back fr’m th’ strate, like ut is. So here I was, comin’ along, whin I hear th’ racket in th’ vacant lot, an’ whin I got there amidst th’ hazel-brush here was this Sally a-hammerin’ this Silas over th’ head wid a bed-slat, an’ him yellin’ bloody-murdther. So I tuck thim up, th’ bot’ iv thim, yer Honor.”

“And that’s all you know of the case?” asked the judge.

“Excipt what she tould me,” said Flaherty.

“And what was that?” asked Judge Murphy.

“Ut was what previnted me from arristin’ her for assault an’ batthery,” said Flaherty, “for if iver a man was assaulted an’ batthered, this same Silas was. She can wield a bed-slat like a warryor.”

“Ah’d ’a’ killed him! Ah’d ’a’ killed him shore!” said Sally.

“She w’u’d!” said Flaherty, briefly. “Thim Naygurs have th’ harrd heads, but wan more whack an’ he’d iv had a crack in th’ cranyum. So I wrested th’ bed-slat from her. Th’ place looked like there’d been a war, yer Honor. Plinty iv thim hazel-brushes she’d mowed down wid th’ bed-slat thryin’ t’ murdther him. An’ whin I heard th’ sthory, I did not blame her.”

“I have been waiting patiently to hear it myself,” said the justice.

“Accordin’ t’ th’ lady,” said Flaherty, “she’s a respictable married woman, yer Honor, bound in th’ clamps iv wedlock to this Noah Prutt, an’ niver stheppin’ t’ wan side iv th’ path iv wifely duty or to th’ other. ’Tis nawthin’ t’ us why a foine-lookin’ gurrl like her sh’u’d marry an’ ould felly like him. Maybe him havin’ two houses atthracted her. I dunno. But, annyway, she’s had t’ wash th’ wolf from th’ doore.”

“Had to do what?” asked the justice.

“Go out doin’ week’s wash t’ kape food in th’ house,” explained Flaherty. “For th’ ould man will not wurrk much. He’s got that used t’ livin’ awn th’ rint iv th’ exthra shanty, ye see. An’ there’s been no rint comin’ in this long whiles, for th’ prisoner at th’ bar has been th’ tinint iv th’ shanty, an’ he ped no rint at all.”

“Why not?” asked the justice.

“Well, sor,” said Flaherty, rubbing the hair at the back of his neck and grinning,[Pg 342] “th’ lady here says he’s been that busy coortin’ her he’s had no time t’ wurrk. ’Twas nawthin’ fr’m wan ind iv th’ week till th’ other but, ‘Will ye elope wid me, darlint?’ an’, ‘Come now, l’ave th’ ould man an’ be me own turtle-dove!’”

“Ah tol’ him Ah gwine murder him ef he gwine keep up dat-a-way of proceedin’!” cried Sally, shrilly. “Ah tol’ him! Ah say, ‘Go on away, you wuthless deadbeat Nigger! Wha’ don’ you pay yo’ rent like a man, befo’ yo’ come talkin’ ’bout supportin’ a lady?’ Dass whut Ah tol’ him, Jedge. An’ whut he say? He say, ‘Sally gal! Ah gwine nab yo’ an’ hab yo’. Ah gwine steal yo’ an’ lock yo’ up, an’ nail yo’ up, an’ keep yo’!’ Dass whut he say. An’ he done hit!”

“Stole you, and locked you up?” asked the judge.

“Yassah!” cried Sally, glaring at the trembling Silas. “He lock me up, an’ he nail me up, an’ he try to drown me, ef Ah ain’ say whut he want me to say. Dat low-down, hypocritical Nigger! Yassah! Ah tole him, ‘Silas, ef yo’ don’ go way an’ leave me alone Ah gwine tek mah hands an’ Ah gwine yank all de wool right offen yo’ haid!’ Dass whut Ah say, Jedge. An’ Ah say, ‘Ef yo’ don’ shet up Ah gwine tear yo’ eyes out!’ An’ Ah means it. Talkin’ up to me like dat! An’ den whut he do?”

She held out her hand toward the dejected Silas and shook her finger at him.

“Den whut he do? He see Ah ain’ to be coax’ dat-a-way, ’cause he a no-’count Nigger, an’ he let on he purtind he get religion an’ wuk on mah feelin’s. Yassah! ’Cause he know Ah’s religious mahsilf an’ he cogitate how he come lak a snake in de grass an’ cotch me whin Ah ain’ thinkin’ no meanness of him. So long come dish yere prophet-man, whut call hisself Obediah, whut get all de Niggers wuk up an’ a-shoutin’ over yonder on de ol’ camp groun’s. Ah am’ tek no stock in dat Obediah prophet-man, Jedge, ’cause Ah a good Baptis’, lak mah husban’ yonder; but plinty of de black folks dey run to him, an’ dey hear him perorate an’ carry on, an’ dey get sot in dere minds dat dey gwine to hebben las’ Tuesday night whin de sun set. Yassah, dass whut dey think, ’cause de prophet-man he pretch dat-a-way. An’ dis yere Silas he let on he gwine to hebben along wid de rest of de folks.”

She let her lip curl scornfully.

“Him a-gwine to hebben!” she scoffed. “But Ah ain’ but half believe he got religion lak he say. Ah say, ‘Luk out, Sally! Ef he gwine to hebben nex’ Tuesday let him go; an’ if he ain’ gwine, let him alone.’ But yo’ look at him, Jedge! Jes look at him! He ain’ look so dangeroos, is he? An’ whin he come to me an’ say, ‘Sally, Ah done got quit of de ol’ Nick whut was in me, an’ Ah gwine be lak dat no mo’,’ Ah jes got to believe him. Yassah! He dat pernicious meek an’ lowly an’ sorrumful-like dat Ah ain’ suspict no divilment at all. ‘Ah feel troubled in mah conscience,’ he say, ‘’cause Ah been tryin’ to lead yo’ on de wrong paff, an’ Ah can’t go to hebben nex’ Tuesday les’ yo’ forgib me,’ he say, an’ he look so downheart’ an’ seem lak he so set on gwine to hebben wid de rest ob de folks, dat Ah say, ‘All right, Silas, Ah don’ hold no hard feelin’s. Ef yo’ don’ bodder me no more, Ah forgib yo’ whut is pas’ an’ done for, but ef yo’ gwine to hebben yo’ better clean up yo’ house an’ put hit in order, lak de Book say, before yo’ start, ’cause ef yo’ don’ yo’ gwine get sint back, shore!’ So he let on lak dat how he think, too. He purtind to thank me kinely fo’ dat recommindation, an’ he ask’ c’u’d Ah lind him a scrub pail an’ a mop an’ a broom, twell he clean up he house. An’ I so done.

“Dass all right! He scrub, an’ he wash, an’ he clean, an’ he move all he furniture out in de lot, an’ he clean, an’ he wash, an’ he scrub! He ain’ wuk lak dat fo’ months, Jedge. So den Ah think shore he got religion, lak he let on. So, come Monday, Ah got a job down to Mis’ Gilbert’s scrubbin’ her house, an’ Ah jes got to hab dat pail an’ dat mop an’ dat broom. So Ah tell Noah whut job Ah got, an’ Ah say, ‘Noah, Ah gwine down to Mis’ Gilbert’s house, fo’ to help clean house, an’ ef she want me, Ah gwine stay right dah twell de house all clean’ up.’ Cause dat a long perambulation down to Mis’ Gilbert’s house, Jedge, an’ ef she ask me to stay a couple o’ days, Ah gwine save mah breakfas’ an’ mah suppah whilst Ah stay down yonder. So Ah go outen de house an’ Ah walk down de street twell Ah come to de gate whut lead up to Silas’ house, an’ Ah walk up de paff, an’ Ah knock on de do’. Nobody say nuffin’! Ah knock ag’in. Nobody say nuffin’! Ah open de do’ gintly, an’ Ah peek in. Ai[Pg 343]n’ nobody in de shack at all. So Ah steps in, fo’ to get mah pail an’ mah mop an’ mah broom.

“Dab dey set, right by de do’, an’ excipt fo’ dem, dey ain’ nuffin’ in de shack at all but de straw outen Silas he’s bed, an’ dat all scatter aroun’ lak to dry an’ air out. Excipt dey one bed-slat whut Ah calculate Silas he keep handy fo’ to whack at de rats, which am mighty pestiferous about dat shack. So whin Ah seen he done clean up yeverything as neat as a pin, my heart soften unto him. Ah jes gwine feel sorry fo’ him, de leas’ little bit. So Ah gwine look in de cupboard to see ef he got plenty to eat—an’ he ain’ got nuffin’ in de cupboard but a box of matches, an’ dat all! So Ah feel right smart sorry I been scold him lak I do, an’ Ah gwine pick up mah pail an’ mah mop an’ mah broom whin—bang!—de do’ go shut an’ Ah all in de dark.”

“Some one shut the door?” asked the justice.

“He shet de do’!” shouted Sally, shrilly, pointing her finger at the trembling Silas. “He shet de do’, an’ he lock de do’, an’ he start to nail de do’, lak he say he would! Yassah! Ah bang mahsilf ag’inst de do’ an’ Ah yell an’ shout, an’ de do’ don’t budge, ’cause hit locked. An’ all de while—bam! bam! bam!—he nailin’ de do’ from de outside. Ah poun’ wif mah fists an’ Ah peck up mah pail an’ slam at de do’ twell de pail all bus’ to pieces, an’ Ah bang mah mop to pieces, but—bam! bam! bam!—he go on nailin’.”

She paused for breath, and Silas opened his mouth, as if to speak, but closed it again.

“Yassah!” she shrilled, glaring at Silas, “he nail up de do’ so Ah can’t budge hit, an’ whin Ah try de windows, dey nailed up too.”

“There’s two iv thim doors,” explained Flaherty, “an’ both iv thim open outward. He’d nailed sthrips acrost thim. Th’ two windys has wooden shutters, and he’d nailed thim fast.”

“What!” exclaimed Justice Murphy. “He nailed the woman in?”

“He did, sor!”

“But—but this is outrageous!” exclaimed the justice.

All three glared at the dejected Silas, and did not see Noah Prutt as he arose from his chair.

“Make him pay, Jedge! Make him pay!” cried Noah, eagerly.

“Sit ye down!” cried Flaherty, in a voice of thunder, and Noah subsided. On the edge of his chair he nodded like a toy mandarin. He understood that things were going badly for Silas, and that was enough to please him. Sally turned to him and shouted in his ear.

“Shet up an’ stay shet!” she cried. “This is none of yo’ business, Noah. Ah gwine manage this mahsilf!”

The old man smiled and nodded his willingness. As she turned away he touched her on the arm.

“Thutty dollahs,” he said, and nodded and smiled again.

“Thutty nuffin’s!” she muttered. “Ah guess yo’ Honor will know whut Ah ought to get from dat Silas, an’ whut he ought to get from yo’. ’Cause Ah suffer a heap o’ distress of min’ an’ body whilst Ah been shet up in dat shanty dem three days.”

“Three days!” exclaimed the justice.

“Yassah! Ah been nail up in dat shanty three days an’ three nights,” said Sally, “an’ all dat time Ah been pestered an’ annoyed. Ah been sploshed on mah feet an’ Ah been hungry an’ col’, an’ Ah been insulted. Dat Silas he jus’ hong roun’ dat shanty to make me mizzable, but Ah ain’ give in one bit. No, sah! Ah’d a-died fus’. Fus’ off Ah bang on de do’ an’ Ah bang on de windows, an’ Ah keep wahm, an’ whin Ah get col’ Ah pile some straw in de fireplace an’ Ah get dem matches an’ Ah mek me a straw fire. An’ prisintly Ah hear Silas scramble-scramble on de roof. ‘Whut he up to now?’ Ah say; ‘He gwine try climb down de chimbly? Ef he do Ah whack him wid de bed-slat twell he mighty sorry he try dat.’ But he ain’ try hit. No, sah! Splosh! come a pail of wahtah down de chimbly, an’ out go mah fire, an’ mah feet suttinly get sopped. An’ Silas he say, down de chimbly, lak he voice all clog up wif laughin’, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit! Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ an’ splosh! yere come anudder pail of wahtah.”

“Why, this is no case for me,” said the justice. “This man should be bound over to the Grand Jury!”

“Ah don’ care whut yo’ bind him to, so as yo’ bind him good an’ strong,” said Sally, vindictively.[Pg 344] “Yevery time Ah try to get wahm by makin’ a fire, down come dat pail of wahtah an’ splosh mah feet, twell Ah think he try to drown me. ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ he shout’. Hit right col’ in dat shanty, Jedge. Hit pernicious col’. Dat wahtah freeze on de flo’, an’ hit freeze on mah shoes, an’ Ah get hungrier an’ hungrier, an’ Ah shout an’ Ah rage, an’ all he say is, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit! Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ Ah bet he ain’! Whin de time come he gwine somewheres ilse!”

“How did you get out, finally?” asked the justice.

“Ah keep maulin’ at de do’ wif dat bed-slat all de whiles,” said Sally. “Dat a mahty fine piece of bed-slat, dat is. An’ prisintly, whin Ah about to drap wid hunger an’ col’ an’ die where Ah drap, Ah beat a hol’ in de do’. ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ he ’low, an’ whack at de bed-slat wif a club, but Ah right smart mad, an’ Ah pry an’ Ah wuk, an’ prisintly Ah pry off one board. An’ when he see Ah gwine win out he scoot. Yassah! He scoot. Ah ’low he run away ’cause he afraid, but dass not hit. No, suh! He gwine fotch an ax, fo’ to nail up dat do’ ag’in. So prisintly Ah wuk dat do’ open an’ Ah step out, an’ whut Ah see? Ah see dat Silas a-standin’ yere in de paff, wid he ax in he hand an’ he mouf wide open, lak Ah been a ghos’. ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit, her?’ Ah say; ‘Well, if yo’ ain’ gone yit, yo’ gwine mighty soon!’ an’ I wint fo’ him wif de bed-slat, an’ he yell lak blazes whilst Ah gwine murder him. An’ dat how-come de pleeceman heah him an’ save he life.”

The justice folded his hands, his fingers working nervously, as if they longed to take hold of the throat of the dispirited prisoner.

“In all my experience,” he said, “this is the most outrageous case I have ever met! I am only sorry I am not the proper official to try this case. I hope this man gets the full penalty of the law. I can’t express—”

He shook his head.

“Whatever possessed you?” he asked the shrinking Silas.

“His Honor is speakin’ t’ ye!” cried Flaherty, poking Silas with his baton. “Spake up whin he addrisses ye! Why did ye do ut?”

“Ah—” began Silas, in a thin, scared voice.

“Sthand up whin ye addriss th’ coort!” said Flaherty, and Silas stood.

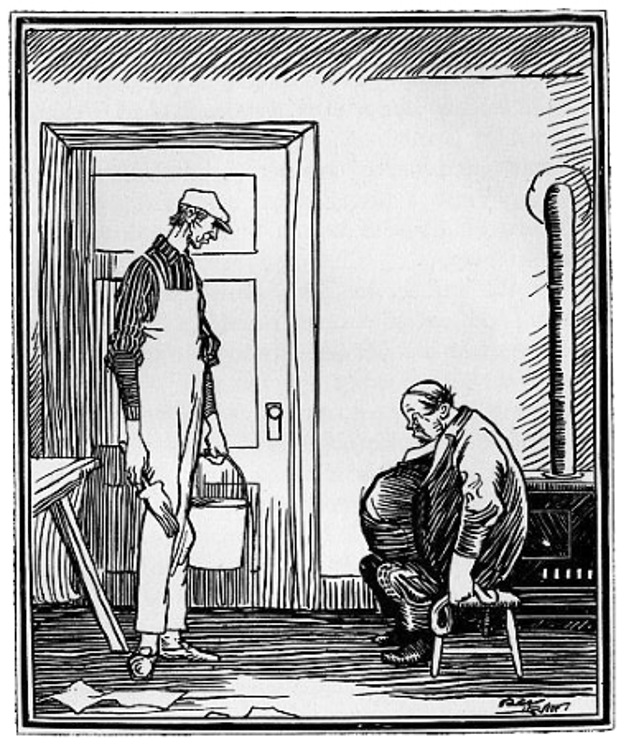

As he stood there was nothing about him that suggested the fiery lover. His drooping shoulders and general air of long-permanent shiftlessness almost gave the lie to the idea that he could have taken the trouble to carry a pail of water to a roof. He looked as if to walk at a shambling gait was about the extreme of any exertion of which he was possible.

“Ah didn’ do hit,” he said weakly, and sat down again.

“Now! now!” said Justice Murphy, sharply. “None of that!”

“Sthand up whin his Honor addrisses ye!” said Flaherty.

“Ah don’ know nuffin’ about hit, Jedge,” said Silas, in a squeaky voice as he half lifted himself out of the chair. “Ah’ll tell yo’ all whut Ah know. Ah wint away from mah shanty Monday, ’cause Ah got to yearn a dollar fo’ to buy a white robe fo’ to go to hebben in Tuesday, an’ Ah chop a cord ob wood an’ yearn mah dollar an’ buy mah white robe. An’ dat night all de prophet’s folks spind de night on de hilltop, a-waitin’ fo’ de dawn ob de great day, an’ a-prayin’ an’ a-singin’ an’ a-fastin’. An’ Tuesday Ah spint awn de hilltop like dat, a-prayin’ an’ a-singin’ an’ a-fastin’ twell de sun sh’u’d set. An’ whin de sun set nuffin’ happen. No, sah. Nobody go nowheres, an’ dey ain’ no prophet no mo’, fo’ he wint away wid whut he done collicted up endurin’ de revival. So whin dat come about Ah quite pertickler hungry, an’ Ah go fo’th t’ yearn some money fo’ to get mah food an’ to pay whut Ah owe Noah, ’cause he been pesterin’ me about he rint. So Ah get some wood to chop, an’ I chop hit. An’ bime-by, whin Ah chop all dat wood, Ah guess Ah’ll go home, an’ Ah go home. An’ whin Ah retch mah shanty, Ah see de do’ bruk, an’ somebody a-yammerin’ on hit, an’ whilst Ah look, out sprong dis Sally Prutt an’ whack me on de haid wid a bed-slat, an’ holler, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit! Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ lak she done gwine crazy, an’ ebbery time she whack she holler, an’ ebbery time she holler she whack. So I gwine get away from dere quick, an’ whin Ah run, she run, an’ she shore gwine murder me, ef dish yere pleeceman am’ come an’ stop her.”

“Just so!” said Justice Murphy, sar[Pg 345]castically. “And you were not near the shanty at all? And you did not nail this woman in it? And you did not pour water down the chimney?”

“No, sah,” said Silas, in a frightened voice.

“Oh, you brack liah!” said Sally, angrily.

“And I suppose you never said, ‘Ain’t gone to heaven yet!’ did you?” said the judge. “You never heard those words, did you?”

Silas looked from side to side, and his lower lip trembled. His back took a more disconsolate droop. There are no words in the English language to describe how utterly downcast and hopeless and woe-saturated he looked. Milton came near it when he said something about “Below the lowest depths still lower depths—” In woe Silas was in depths a couple of stories lower than that.

“Well?” said the justice, sharply.

“Answer his Honor whin he addrisses ye!” shouted Flaherty, and Silas moistened his lips and gulped.

“No, sah! Ah—Ah ain’ hear them wuds perzackly, nevah befo’. Ah ain’ heah, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben.’ Ah jes heah ‘Ain’ gwine to hebben.’”

“Oh, you did hear that, did you?” said the justice. “Who said that?”

Silas stared at his boot. He blinked a couple of times, and then spoke.

“Ol’ Noah, he say thim wuds,” he said. The judge turned to the old Negro on the chair in the front row, and pointed at him.

“That Noah?” he asked. “Is that the man?”

“Yassah,” said Silas, sadly. “Dass de man. He say hit.”

Old Noah, seeing that the conversation was veering his way, arose and came forward, his hand behind his ear and expectation in his face.

“Thutty dollahs, Jedge!” he said eagerly. “Dass de right amount. Thutty dollahs.”

“You go set down!” yelled his wife in his ear, but the old man shook his head.

“Ain’ he gwine pay hit?” he asked resentfully. “Ain’ de jedge gwine mek him pay hit? Whaffo’ Ah nail up de shack ef he ain’ gwine pay hit?”

“Whut yo’ palaver about? Nail up de shack! You ain’ nail up no shack. Dat no-’count Silas he nail up de shack,” shouted Sally.

The old man nodded his head and grinned.

“Yas, dasso! Dasso! Ah nail up de shack, Jedge,” he chuckled. “Ah nail him in. Yassah, Ah done jes so.”

“Him?” shouted the justice, “you mean her?”

“Yassah, Ah nail him in,” said Noah.

“You did?” shouted the justice.

“Ah—Ah beg pawdon, Jedge,” said the old man. “Ah cawn’t heah as—as well as Ah used to heah. Ah cawn’t hear whisperin’ tones no moah. Ah—Ah got to beg yo’ to speak jes a leetle mite louder.”

“WHY DID YOU NAIL HIM IN THE SHACK?” shouted Justice Murphy at the top of his voice.

“Why, ’cause he won’ pay me de rint,” said Noah, as if it was a thing every one should have known. “Ain’ Sally been jes tol’ yo’? Ah surmise she done confabulate about that all de whiles she talkin’. Yo’ mus’ scuse her, Jedge. Whin de womens staht talkin’, nobuddy know whut dey talk about. Dey jes talk fo’ de exumcise. Mah secon’ wife, which am de las’ but one befo’ Ah tuck Sally—”

“Look here!” shouted Justice Murphy. “Why did you nail him in the shack?”

“Zack?” said the old man, doubtfully.[Pg 346] “No, sah, he name Silas. Dass him yondah. I arsk him fo’ de rint, an’ I beg him fo’ de rint, an’ I argyfy about dat rint twell Ah jes wohn out, an’ Ah don’ git no rint at all. So bime-by erlong come dish yere prophet whut you heah about, maybe. Ah ain’ tek no stock in dat prophet-man at all! No, sah! Ah ’s a good Baptis’ an’ Ah don’ truckle to none o’ dem come-easy, go-easy, folks like dat. Ah stay ’way from him, an’ Ah tell Sally she stay way likewise. But dis yere Silas he get de prophet-man’s religion bad. Yassah. He ’low he gwine to hebben las’ Tuesday whin all de res’ ob de gang go. Ah reckon he ain’ gwine go, ’cause Ah feel dey ain’ none ob dem gwine go, but Ah can’t be shore. Mos’ anything li’ble to happen whin times so bad like dey is. So Ah projeck up to Silas an’ Ah say to him, ‘Ef yo’ gwine to hebben nex’ Tuesday, yo’ bettah pay me de rint befo’ yo’ go.’ Dass whut Ah say, Jedge. An’—an’—an’ dass reason-able. ’Cause ef he gwine to hebben Tuesday, Ah ain’ gwine hab no chance to collict dat rint come Winsday. No, sah.”

“Then what?” shouted the justice.

“Nuffin’!” said Noah. “Nuffin’ at all. He say, ‘Scuse me, Noah, but Ah so full ob preparations fo’ de great evint Ah ain’ got time to yearn no money to pay de rint.’ An’ Ah say, ‘Silas, Ah want mah rint!’ So, bime-by, whin Monday mawrnin’ come erlong, Sally she gwine away to do a job o’ work, an’ Ah meyander ober to Silas’ shack, an’ Ah got mah hatchit an’ mah nails, whut Ah gwine mind de fince. An’ whin Ah come to de shack All hear de squawk ob a board in de flo’ an’ Ah know Silas he in de shack, an’ Ah slam de do’ an’ Ah nail up de do’ an’ he carrye on scandalous, but he can’t git yout. An’ Ah don’ care whut he say, ’cause Ah can’t heah ef he cuss or ef he palaver.

“’Cause Ah ain’ gwine hab no tinint go to hebben like dat whin he owe me rint twell he pay de rint. So Ah reckon Ah leave him dere twell de gwine is all gone, an’ Ah ain’ worried erbout Silas gwine alone by hisse’f. He ain’ got de get-up to do nuffin’ alone by hisse’f. So Ah leab him dah twell he natchully bus’ out.”

“You tried to starve him,” shouted the justice. “You threw water down the chimney.”

“Dass jes a pre-caution, Jedge, dass jes a pre-caution,” said the old Negro. “Ah got mah doubts erbout dat ol’ Obediah prophet-man whut come from nowhares. Whin Ah see de smoke a-risin’ from de chimbly, Ah speculate ef et hebben whar de prophet-man gwine tek they-all, or ef he gwine tek dem ilsewhars, an’ Ah cogitate how maybe Silas gwine escape in de flame ob de fiah. Dey yain’t nuffin’ like good ol’ Baptis’ water fo’ to fight debbil’s fiah, so Ah fotch a couple o’ pail’ ob wahtah, an’ Ah po’ hit down de chimbly, an’ Ah say, ‘Yo’ ain’ gwine to hebben yit! Yo’ ain’ gwine to hebben yit!’ Yassah. An’ he ain’!”

He chuckled with glee, but at the same moment he caught a glimpse of Sally’s face, and his grin gave way to a look of blank surprise. Slowly and carefully Sally was rolling up her sleeves, and her eyes glittered menacingly. Flaherty tapped her on the shoulder.

“None iv that here!” he said sternly.

The justice looked from one to the other of the parties before him, closed an impressive-looking law book with a bang, and stood up, feeling for his tobacco-pipe in his hip pocket.

“Flaherty,” he said slowly, “this is not a case for this court. It seems in the nature of a domestic misunderstanding. Under ordinary circumstances,” he added, pressing tobacco into the pipe with his thumb, “I should undertake to explain to all parties just what happened and how it happened and why it happened but—” he looked at old Noah and shook his head—“there is nothing in the statutes of the State of Iowa compelling a justice of the peace of the County of Riverbank, City of Riverbank and Township of Riverbank, to shout that loud and that long. Case dismissed!”

Flaherty herded the three parties out of the room and the justice lighted his pipe.

“Whaffo’ Ah ain’ git mah thutty dollahs?” he heard Uncle Noah ask in the hall. “Wha’ we gwine?”

“Ah tell yo’ wha’ yo’ ain’ gwine!” he heard Sally shout. “You ain’ gwine to hebben yit! But yo’ gwine to wish yo’ was gwine ’fo’ Ah git froo wif yo’!”

“Flaherty,” said his Honor, tilting back comfortably and blowing a cloud of blue smoke toward the ceiling, “go out and warn that woman to keep the peace.”

“I will,” said Flaherty, “but can ye ixpict ut iv her, Murphy?”