THE OUBLIETTE

by Ellis Parker Butler

The discovery that Syrilla was the daughter of Jonas Medderbrook (born Jones) was a great triumph for Philo Gubb, but while the “Riverbank Eagle” made a great hurrah about it, Philo Gubb was not entirely happy over the matter. Having won a reward of ten thousand dollars for discovering Syrilla and five hundred dollars for recovering Mr. Medderbrook’s golf cup, Mr. Gubb might have ventured to tell Syrilla of his love for her but for three reasons.

The first reason was that Mr. Gubb was so bashful that it was impossible for him to speak his love openly and immediately. If Syrilla had returned to Riverbank with her father, Mr. Gubb would have courted her by degrees, or if Syrilla had weighed only two hundred pounds, Mr. Gubb might have had the bravery to propose to her instantly, but she weighed one thousand pounds, and it required five times the bravery to propose to a thousand pounds that was required to propose to two hundred pounds.

The second reason was that Mr. Dorgan, the manager of the side-show, would not release Syrilla from her contract.

“She’s a beauty of a Fat Lady,” said Mr. Dorgan, “and I’ve got a five-year contract with her and I’m going to hold her to it.”

Mr. Medderbrook and Mr. Gubb would have been quite hopeless when Mr. Dorgan said this if Syrilla had not taken them to one side.

“Listen, dearies,” she said, “he’s a mean, old brute, but don’t you fret! I got a hunch how to make him cancel my contract in a perfectly refined an’ ladylike manner. Right now I start in bantin’ and dietin’ in the scientific-est manner an’ the way I can lose three or four hundred pounds when I set out to do it is something grand. It won’t be no time at all until I’m thin and wisp-like, an’ Mr. Dorgan will be glad to get rid of me.”

This information greatly cheered Mr. Gubb. While he admired Syrilla just as she was, a rapid mental calculation assured him that she would still be quite plump at seven hundred pounds and he knew he could love seven tenths of Syrilla more than he could love ten tenths of any other lady in the world.

The third reason had to do with the ten-thousand-dollar reward. When Mr. Gubb and Mr. Medderbrook were proceeding homeward on the train, Mr. Medderbrook brought up the subject of the reward again.

“I’m going to pay you that ten thousand dollars, Gubb,” he said, “but I’m going to pay it so it will be worth a lot more than ten thousand dollars to you.”

“You are very overly kind,” said Mr. Gubb.

“It’s because I know you are fond of Syrilla,” said Mr. Medderbrook.

Mr. Gubb blushed.

“So I ain’t going to give you ten thousand dollars in cash,” said Mr. Medderbrook. “I’m going to do a lot better by you than that. I’m going to give you gold-mine stock. The only trouble—”

“Gold-mine stock sounds quite elegantly nice,” said Mr. Gubb.

“The only trouble,” said Mr. Medderbrook, “is that the gold-mine stock I want to give you is in a block of twenty-five thousand dollars. It’s nice stock. It’s as neatly engraved as any stock I ever saw, and it is genuine common stock in the Utterly Hopeless Gold-Mine Company.”

“The name sounds sort of unhopeful,” ventured Mr. Gubb timidly.

“That shows you don’t know anything about gold mines,” said Mr. Medderbrook cheerfully. “The reason I—the reason the miners gave it that name is because this mine lies right between two of the best gold-mines in Minnesota. One of them is the Utterly Good Gold-Mine, and the other is the Far-From-Hopeless. So when I—so when the miners named this mine they took part of the names of the two others and called this one the Utterly Hopeless. That’s the way I—the way it is always done.”

“It’s very cleverly bright,” said Mr. Gubb.

“It’s an old trick—I should say an old and approved method,” said Mr. Medderbrook. “So what I’m going to do, Mr. Gubb, is to let you in on the ground floor on this mine. It’s a chance I wouldn’t offer to everybody. This mine hasn’t paid out all its money in dividends. I tell you as an actual fact, Mr. Gubb, that so far it hasn’t paid out a cent in dividends, not even to the preferred stock. No, sir! And it ain’t one of these mines that has been mined until all the gold is mined out of it. No, sir! Not an ounce of gold has ever been taken out of the Utterly Hopeless Mine. Not an ounce.”

“It is all there yet!” exclaimed Mr. Gubb.

“All there ever was,” said Mr. Medderbrook. “Yes, sir! If you want me to I’ll give you a written guarantee that the Utterly Hopeless Mine has never paid a cent in dividends and that not an ounce of gold has ever been taken out of the mine. That shows you I’m square about this. So what I’m going to do,” he said impressively, “is to turn over to you a block of twenty-five thousand dollars’ worth of Utterly Hopeless Gold-Mine stock and apply the ten thousand dollars I owe you as part of the purchase price. All you need to do then is to pay me the other fifteen thousand dollars as rapidly as you can.”

“That’s very kindly generous of you,” said Mr. Gubb gratefully.

“And that isn’t all,” said Mr. Medderbrook. “I own every single share of the stock of that mine, Mr. Gubb, and as soon as you get the fifteen thousand dollars paid up I’ll advance the price of that stock one hundred per cent! Yes, sir, I’ll double the price of the stock, and what you own will be worth fifty thousand dollars!”

There were tears in Philo Gubb’s eyes as he grasped Mr. Medderbrook’s hand.

“And all I ask,” said Mr. Medderbrook, “is that you hustle up and pay that fifteen thousand dollars as quick as you can. So that,” he added, “you’ll be worth fifty thousand dollars all the sooner.”

Upon reaching Riverbank Mr. Medderbrook took Mr. Gubb to his home and turned over to him the stock in the Utterly Hopeless Mine.

“And here,” said Mr. Medderbrook, “is a receipt for ten thousand five hundred dollars, and you can give me back that five hundred I paid you for recovering of my golf cup. That’s to show you everything is fair and square when you deal with me. Now you owe me only fourteen thousand five hundred dollars.”

While Mr. Gubb was handing the five hundred dollars back to Mr. Medderbrook the colored butler entered with a telegram. Mr. Medderbrook tore it open hastily.

“Good news already,” he said and handed it to Mr. Gubb. It was from Syrilla and said:—

Be brave. Have lost four ounces already. Kind regards and best love to Mr. Gubb.

With only partial satisfaction Mr. Gubb left Mr. Medderbrook and proceeded downtown. He now had a double incentive for seeking the rewards that fall to detectives, for he had Syrilla to win and the Utterly Hopeless Gold-Mine stock to pay for. He started for the Pie-Wagon, for he was hungry, but on the way certain suspicious actions of Joe Henry (the liveryman who had twice beaten him up while he was working on the dynamiter case), stopped him, and it was much later when he entered the Pie-Wagon.

As Philo Gubb entered, Billy Getz sat on one of the stools and stirred his coffee. He held a dime novel with his other hand, reading; but Pie-Wagon Pete kept an eye on him. He knew Billy Getz and his practical jokes. If unwatched for a moment, the young whipper-snapper might empty the salt into the sugar-bowl, or play some other prank that came under his idea of fun.

Billy Getz was a good example of the spoiled only son. He went in for all the vice there was in town, and to occupy his spare time he planned practical jokes. He was thirty years old, rather bald, had a pale and leathery skin, and a preternaturally serious expression. In his pranks he was aided by the group of young poker-playing, cigarette-smoking fellows known as the “Kidders.”

Billy Getz, as he read the last line of the thrilling tale of “The Pale Avengers,” tucked the book in his pocket, and looked up and saw Philo Gubb. The hawk-eyes of Billy Getz sparkled.

“Hello, detective!” he cried. “Sit down and have something! You’re just the man I’ve been lookin’ for. Was askin’ Pete about you not a minute ago—wasn’t I, Pete?”

Pie-Wagon Pete nodded.

“Yes, sir,” said Billy Getz eagerly, “I’ve got something right in your line—something big; mighty big—and—say, detective, have you ever read ‘The Pale Avengers’?”

“I ain’t had that pleasure, Mr. Getz,” said Philo Gubb, straddling a stool.

“What’s the matter? You’re out of breath,” said Pie-Wagon.

“I been runnin’,” said Philo Gubb. “I had to run a little. Deteckatives have to run at times occasionally.”

“You bet they do,” said Billy Getz earnestly. “You ain’t been after the dynamiters, have you?”

“I am from time to time working upon that case,” said Philo Gubb with dignity.

“Well, you be careful. You be mighty careful! We can’t afford to lose a man like you,” said Billy Getz. “You can’t be too careful. Got any of the ghouls yet?”

“Not yet,” said Philo Gubb stiffly. “It’s a difficult case for one that’s just graduated out of a deteckative school. It’s like Lesson Nine says—I got to proceed cautiously when workin’ in the dark.”

“Or they’ll get you before you get them,” said Billy Getz. “Like in ‘The Pale Avengers.’ Here, I want you to read this book. It’ll teach you some things you don’t know about crooks, maybe.”

“Thank you,” said Philo Gubb, taking the dime novel. “Anything that can help me in my deteckative career is real welcome. I’ll read it, Mr. Getz, and—Look out!” he shouted, and in one leap was over the counter and crouching behind it.

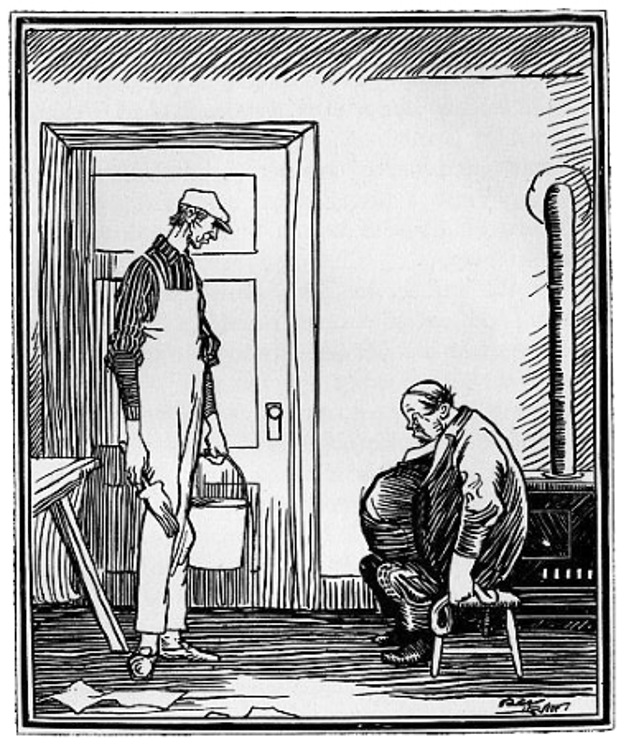

Billy Getz turned toward the door, where a short, red-faced man was standing with a pine slab held in his hand. Intense anger glittered in his eyes, and he darted to the counter and, leaning over, brought the slab down on Philo Gubb’s back with a resounding whack.

“Here! Here! None o’ that stuff in here, Joe,” cried Pie-Wagon Pete, grasping the intruder’s arm.

“I’ll kill him, that’s what I’ll do!” shouted the intruder. “Snoopin’ around my place, and follerin’ me up an’ down all the time! I told him I wasn’t goin’ to have him doggin’ me an’ pesterin’ me. I’ve beat him up twice, an’ now I’m goin’ to give him the worst lickin’ he ever had. Come out of there, you half-baked ostrich, you.”

“Now, you stop that,” said Pie-Wagon Pete sternly. “You’re goin’ to be sorry if you beat him up. He don’t mean no harm. He’s just foolish. He don’t know no better. All you got to do is to explain it to him right.”

“Explain?” said Joe Henry. “I’d look nice explainin’ anything, wouldn’t I? Hand him over here, Pete.”

“Now, listen,” shouted Pie-Wagon Pete angrily. “You ain’t everything. I’m your pardner, ain’t I? Well, you let me fix this.” He winked at Joe Henry. “You let me explain to Mr. Gubb, an’ if he ain’t satisfied, why—all right.”

For a moment Joe Henry studied Pie-Wagon’s face, and then he put down the slab.

“All right, you explain,” he said ungraciously, and Philo Gubb raised his white face above the counter.

Upon the passage of the State prohibitory law every saloon in Riverbank had been closed and there had been growlings from the saloon element. Five of the leading prohibitionists had received threatening letters and, a few nights later, the houses of four of the five were blown up. Kegs of powder had been placed in the cellar windows of each of the four houses, wrecking them, and the fifth house was saved only because the fuse there was damp. Luckily no one was killed, but that was not the fault of the “dynamiters,” as every one called them.

The town and State immediately offered a reward of five thousand dollars for the arrest and conviction of the dynamiters, and detectives flocked to Riverbank. Real detectives came to try for the noble prize. Amateur detectives came in hordes. Citizens who were not detectives at all tried their hands at the work.

For the first few days rumors of the immediate capture of the “ghouls” were flying everywhere, but day followed day and week followed week, and no one was incarcerated. The citizen-detectives went back to their ordinary occupations, the amateur detectives went home, the real detectives were called off on other and more promising jobs, and soon the field was left clear for Philo Gubb.

Not that he made much progress. Each night he hid himself in the dark doorway of Willcox Hall waiting to pick up (Lesson Four, Rule Four) some suspicious-looking person, and having picked him up, he proceeded to trail and shadow him (Lesson Four, Rules Four to Seventeen). Six times—twice by Joe Henry—he was well beaten by those he followed. It became such a nuisance to be followed by Philo Gubb in false mustache or whiskers, that it was a public relief when Billy Getz and other young fellows took upon themselves the duty of being shadowed. With hats pulled over their eyes and coat-collars turned up, they would pass the dark doorway of Willcox Hall, let themselves be picked up, and then lead poor Detective Gubb across rubbish-encumbered vacant lots, over mud flats or among dark lumber piles, only to give him the slip with infinite ease when they tired of the game.

But Philo Gubb was back the next night, waiting in the shadow of the doorway of Willcox Hall. He did not progress very rapidly toward the goal of the reward, but he counted it all good practice.

But being beaten twice in succession by Joe Henry aroused his suspicion.

Joe Henry ran a small carting business. He had three teams and three drays, and a small stable on Locust Street, on the alley corner. He was a great friend of Pie-Wagon Pete and he ate at the Pie-Wagon.

Philo Gubb, after leaving Mr. Medderbrook, had not intentionally picked up Joe Henry. On his way to the Pie-Wagon it had been necessary for him to pass the alley opposite Joe Henry’s stable and his detective instinct told him to hide himself behind a manure bin in the alley and watch the stable. In the warm June dusk he had crouched there, watching and waiting.

Mr. Gubb could see into the stable, but there was not much to see. The stable boy sat at the door, his chair tipped back, until a few minutes after eleven, when one of Joe Henry’s drays drove up with a load of baled hay.

Philo Gubb heard the voices of the men as they hoisted the hay to the hay-loft, and he saw Joe Henry helping with the hoisting-rope. The hay was water-soaked. Water dripped from it onto the floor of the stable.

But nothing exciting occurred, and Philo Gubb was about to consider this a dull evening’s work, when Joe Henry appeared in the doorway, a pitchfork in one hand and the slab of pine in the other. He looked up and down the street and then, with surprising agility, sprang across the street toward where Philo Gubb lay hid. With a wild cry, Philo Gubb fled. The pitchfork clattered at his feet, but missed him, and he had every advantage of long legs and speed. His heels clattered on the alley pave, and Joe Henry’s clattered farther and farther behind at each leap of the Correspondence School detective.

“All right, you explain,” said Joe Henry sullenly.

“Now you ain’t to breathe a word of this, cross-your-heart, hope-to-die, Philo Gubb. Nor you neither, Billy,” said Pie-Wagon Pete. “Listen! Me an’ Joe Henry ain’t what we let on to be. That’s why we don’t want to be follered. We’re detectives. Reg’lar detectives. From Chicago. An’ we’re hired by the Law an’ Order League to run down them gools. We’re right clost onto ’em now, ain’t we, Joe? An’ that’s why we don’t want to have no one botherin’ us. You wouldn’t want no one shadowin’ you when you was on a trail, would you, Gubby?”

“No, I don’t feel like I would,” admitted Philo Gubb.

“That’s right,” said Pie-Wagon Pete approvingly. “An’ when these here dynamite gools is the kind of murderers they is, an’ me and Joe is expectin’ to be murdered by them any minute, it makes Joe nervous to be follered an’ spied on, don’t it, Joe?”

“You bet,” said Joe. “I’m liable to turn an’ maller up anybody I see sneakin’ on me. I can’t take chances.”

“So you won’t interfere with Joe in the pursoot of his dooty no more, will you, Gubby?” said Pie-Wagon Pete.

“I don’t aim to interfere with nobody, Peter,” said Philo Gubb. “I just want to pursoo my own dooty, as I see it. I won’t foller Mr. Henry no more, if he don’t like it; but I got a dooty to do, as a full graduate of the Rising Sun Deteckative Agency’s Correspondence School of Deteckating. I got to do my level best to catch them dynamiters myself.”

Joe Henry frowned, and Pie-Wagon Pete shook his head.

“If you’ll take my advice, Gubby,” he said, “you’ll drop that case right here an’ now. You don’t know what dangerous characters them gools are. If they start to get you—”

“You want to read that book—‘The Pale Avengers’—I just gave you,” said Billy Getz, “and then you’ll know more.”

“Well, I won’t interfere with you, Mr. Henry,” said Philo Gubb. “But I’ll do my dooty as I see it. Fear don’t frighten me. The first words in Lesson One is these: ‘The deteckative must be a man devoid of fear.’ I can’t go back on that. If them gools want to kill me, I can’t object. Deteckating is a dangerous employment, and I know it.”

He went out and closed the door.

“There,” said Pie-Wagon Pete. “Ain’t that better than beatin’ him up?”

“Maybe,” said Joe Henry grudgingly. “Chances are—he’s such a dummy—he’ll go right ahead follerin’ me. He needs a good scare thrown into him.”

Billy Getz slid from his stool and ran his hands deep into his pockets, jingling a few coins and a bunch of keys.

“Want me to scare him?” he asked pleasantly.

“Say! You can do it, too!” said Joe Henry eagerly. “You’re the feller that can kid him to death. Go ahead. If you do, I’ll give you a case of Six Star. Ain’t that so, Pete?”

“Absolutely,” said Pie-Wagon.

“That’s a bet,” said Billy Getz pleasantly. “Leave it to the Kidders.”

Philo Gubb went straight to his room at the Widow Murphy’s, and having taken off his shoes and coat, leaned back in his chair with his feet on the bed, and opened “The Pale Avengers.” He had never before read a dime novel, and this opened a new world to him. He read breathlessly. The style of the story was somewhat like this:—

The picture on the wall swung aside and Detective Brown stared into the muzzles of two revolvers and the sharp eyes of the youngest of the Pale Avengers. A thrill of horror swept through the detective. He felt his doom was at hand. But he did not cringe.

“Your time has come!” said the Avenger.

“Be not too sure,” said Detective Brown haughtily.

“Are you ready to die?”

“Ever ready!”

The detective extended his hand toward the table, on which his revolver lay. A cruel laugh greeted him. It was the last human voice he was to hear. As if by magic the floor under his feet gave way. Down, down, down, a thousand feet he was precipitated. He tried to grasp the well-like walls of masonry, but in vain. Nothing could stay him. As he plunged into the deep water of the oubliette a fiendish laugh echoed in his ears. The Pale Avengers had destroyed one more of their adversaries.

Until he read this thrilling tale, Philo Gubb had not guessed the fiendishness of malefactors when brought to bay, and yet here it was in black and white. The oubliette—a dark, dank dungeon hidden beneath the ground—was a favorite method of killing detectives, it seemed. Generally speaking, the oubliette seemed to be the prevailing fashion in vengeful murder. Sometimes the bed sank into the oubliette; sometimes the floor gave way and cast the victim into the oubliette; sometimes the whole room sank slowly into the oubliette; but death for the victim always lurked in the pit.

Before getting into bed Philo Gubb examined the walls, the floor, and the ceiling of his room. They seemed safe and secure, but twice during the night he awoke with a cry, imagining himself sinking through the floor.

Three nights later, as Philo Gubb stood in the dark doorway of the Willcox Building waiting to pick up any suspicious character, Billy Getz slipped in beside him and drew him hastily to the back of the entry.

“Hush! Not a word!” he whispered. “Did you see a man in the window across the street? The third window on the top floor?”

“No,” whispered Philo Gubb. “Was—was there one?”

“With a rifle!” whispered Billy Getz. “Ready to pick you off. Come! It is suicide for you to try to go out the front way now. Follow me; I have news for you. Step quietly!”

He led the paper-hanger through the back corridor to the open air and up the outside back stairs to the third floor and into the building. He tapped lightly on a door and it was opened the merest crack.

“Friends,” whispered Billy Getz, and the door opened wide and admitted them.

The room was the club-room of the Kidders, where they gathered night after night to play cards and drink illicit whiskey. Green shades over which were hung heavy curtains protected the windows. A large, round table stood in the middle of the floor under the gas-lights; a couch was in one corner of the room; and these, with the chairs and a formless heap in a far corner, over which a couch-cover was thrown, constituted all the furniture, except for the iron cuspidors. Here the young fellows came for their sport, feeling safe from intrusion, for the possession of whiskey was against the law. There was a fine of five hundred dollars—one half to the informer—for the misdemeanor of having whiskey in one’s possession, but the Kidders had no fear. They knew each other.

For the moment the cards were put away and the couch-cover hid the four cases of Six Star that represented the club’s stock of liquor. The five young men already in the room were sitting around the table.

“Sit down, Detective Gubb,” said Billy Getz. “Here we are safe. Here we may talk freely. And we have something big to talk to-night.”

Philo Gubb moved a chair to the table. He had to push one of the cuspidors aside to make room, and as he pushed it with his foot he saw an oblong of paper lying in it among the sand and cigar stubs. It was a Six Star whiskey label. He turned his head from it with his bird-like twist of the neck and let his eyes rest on Billy Getz.

“We know who dynamited those houses!” said Billy Getz suddenly. “Do you know Jack Harburger?”

“No,” said Philo Gubb. “I don’t know him.”

“Well, we do,” said Billy Getz. “He’s the slickest ever. He was the boss of the gang. Read this!”

He slid a sheet of note-paper across to Philo Gubb, and the detective read it slowly:—

Billy: Send me five hundred dollars quick. I’ve got to get away from here.J. H.

“And we made him our friend,” said Billy Getz resentfully. “Why, he was here the night of the dynamiting—wasn’t he, boys?”

“He sure was,” said the Kidders.

“Now, he’s nothing to us,” said Billy Getz. “Now, what do you say, Detective Gubb? If we fix it so you can grab him, will you split the reward with us?”

“Half for you and half for me?” asked Philo Gubb, his eyes as big as poker chips.

“Three thousand for you and two for us, was what we figured was fair,” said Billy Getz. “You ought to have the most. You put in your experience and your education in detective work.”

“And that ought to be worth something,” admitted Philo Gubb.

So it was agreed. They explained to Philo Gubb that Jack Harburger was the son of old Harburger of the Harburger House at Derlingport, and that they could count on the clerk of that hotel to help them. Billy Getz would go up and get things ready, and the next day Philo Gubb would appear at the hotel—in disguise, of course—and do his part. The clerk would give him a room next to Jack Harburger’s room, and see that there was a hidden opening in the partition; and Billy Getz, pretending he was bringing the money, would wring a full confession from Jack Harburger. Then Philo Gubb need only step into the room and snap the handcuffs on Jack Harburger and collect the reward.

They shook hands all ’round, finally, and Billy Getz went to the window to see that no ghoul was lurking in the street, ready to murder Philo Gubb when he went out. As he turned away from the window the toe of his shoe caught in the fringe of the couch-cover and dragged it partially from the odd-shaped pile in the corner. With a quick sweep of his hand Billy Getz replaced the cover, but not before Philo Gubb had seen the necks of a full case of bottles and had caught the glint of the label on one of them, bearing the six silver stars, like that in the cuspidor. Billy Getz cast a quick glance at the Correspondence School detective’s face, but Philo Gubb, his head well back on his stiff neck, was already gazing at the door.

Two days later Philo Gubb, with his telescope valise in his hand, boarded the morning train for Derlingport. The river was on one of its “rampages” and the water came close to the tracks. Here and there, on the way to Derlingport, the water was over the tracks, and in many places the wagon-road, which followed the railway, was completely swamped, and the passing vehicles sank in the muddy water to their hubs. The year is still known as the “year of the big flood.” In Riverbank the water had flooded the Front Street cellars, and in Derlingport the sewers had backed up, flooding the entire lower part of the town.

When the train reached Derlingport Philo Gubb, with his telescope valise, which contained his twelve Correspondence School lessons, “The Pale Avengers,” a pair of handcuffs, his revolver, and three extra disguises, walked toward the Harburger House. He was already thoroughly disguised, wearing a coal-black beard and a red mustache and an iron-gray wig with long hair. Luckily he passed no one. With that disguise he would have drawn an immense crowd. Nothing like it had ever been seen on the streets of Derlingport—or elsewhere, for that matter.

A full block away Philo Gubb saw the sign of the hotel, and he immediately became cautious, as a detective should. He crossed the street and observed the exits. There was a main entrance on the corner, a “Ladies’ Entrance” at the side, and an entrance to what had once been the bar-room. From the fire-escape one could drop to the street without great injury.

Philo Gubb noted all these, and then walked to the alley. There were two doors opening on the alley—one a cook’s door, and the other evidently leading to the cellar. At the latter a dray stood, and as Philo Gubb paused there, two men came from this door and laid a bale of hay on the dray, pushing it forward carefully. They did not toss it carelessly onto the dray but slid it onto the dray. And the hay was wet. Moreover, the two men were two of Joe Henry’s men, and that was odd. It was odd that Joe Henry should send a dray the full thirty miles to Derlingport to get a load of wet hay, when he could get all the dry hay he wanted in Riverbank. But it did not impress Philo Gubb. He hurried to the main entrance of the hotel, and entered.

The lobby of the Harburger House was large, and gloomy in its old-fashioned black-walnut woodwork. Except for one man sitting at a desk by the window and writing industriously, and the clerk behind the counter, the lobby was untenanted. To the left a huge stairway led to the gloom above, for the hotel boasted no elevator except the huge “baggage lift,” which had been put in in the palmy days of the house, when the great river packets were still a business factor.

Philo Gubb walked across the lobby to the clerk’s desk. The industrious penman by the window glanced over his shoulder. He looked more like a hotel clerk than like a traveling salesman, but Philo Gubb gave this no thought. The clerk behind the desk put his fingers on his lips.

“Sh!” he whispered. “Are you Detective Gubb? Good! I’ve been expecting you. Have you a gun?”

“In my telescope case,” whispered Philo Gubb.

“Take this one,” said the clerk, handing the paper-hanger-detective a glittering revolver. “Be careful. Come—I’ll show you the room.”

He came from behind the desk and picked up Philo Gubb’s telescope valise and led the way up the dingy stairway. Luckily for Billy Getz’s great practical joke, Philo Gubb had never seen Jack Harburger, or he would have recognized him in the plump little man carrying his telescope valise. Up three flights of dark stairs, Jack Harburger led Philo Gubb, and at the landing of the fourth floor he stopped.

“You were taking a risk—a big risk—coming undisguised,” he said.

“But I am disguised,” said Philo Gubb. “These here is false whiskers and hair.”

“What!” exclaimed Jack Harburger. “Wonderful work! A splendid make-up, detective! You fooled me with it, and I was on my guard. You’ll do. Bend down like an old man. That’s it! Now, listen: I have cut a hole through the wall from your room into Jack’s. You can hear every word he speaks. Have you pencil and paper? Good! Jot down every word you hear. And don’t make a sound. If you are discovered—well, they’re a desperate gang. Come!”

He led the way through a long, dark corridor that turned and twisted. At the extreme end he stopped, put down the telescope valise, and drew a key from his pocket.

“That’s Jack’s room,” he breathed softly, “and you go in here. Sorry it isn’t a better room. We had to use it, and you won’t be here long, anyway.”

He opened the door. It was a large door that swung outward, and it occupied one half of one side of the room. The floor of the room was carpeted, and the walls were papered, as was the ceiling. There was no window, but an electric light burned in the center of the ceiling. Across the far side of the room stood a narrow iron bed, with a small bureau beside it. Jack Harburger pointed to a hole in the wall-paper.

“That’s your ear-hole,” he whispered, and Philo Gubb stepped into the room. Instantly the door slammed behind him, the key turned in the lock, and he heard a heavy iron bar clank as it fell into place outside. He was a prisoner, caught like a rat in a trap, and he knew it! He threw himself against the door, but it did not give. The electric light above his head went dark. He put out his hand, and the wall gave slightly. He drew the revolver and waited, dreading what might next occur. He heard soft footsteps outside the door, and, raising the revolver, pulled the trigger. The trigger snapped harmlessly. He had been tricked, tricked all around.

“Is the oubliette prepared?” whispered a voice outside.

“All ready for him. Twelve feet of water. He’ll drown like a rat.”

“Good. A slow death, like a rat in a trap—like we served the other two. Then get rid of his body the same way.”

“A stone on it, and the river?”

“Yes. They never come up again.”

The voices died away along the corridor, and Philo Gubb was left in utter silence. Oubliette! The fate of the detectives of “The Pale Avengers” was to be his! Suddenly the room began to quiver. The floor and the walls trembled and creaked, and Philo Gubb threw himself once more against the door. He shouted and beat upon it with his hands. Inch by inch, creaking and swaying, the room glided downward. The door seemed to glide upward beyond the ceiling, giving place to a solid wall. He turned and beat on the side of the room, and it gave forth a hollow sound. As he moved, the room swayed under his feet. He was doomed!

Alone in the darkness, his fear suddenly gave way to a feeling of pride. He was dangerous enough, then, to be thought worthy of death? His last drop of doubt oozed out of his mind. He was—he must be—a great detective, or such means would not have been taken to get rid of him. He felt a sort of calm joy in this. His murderers knew his prowess.

Locked in the room, going down to certain death, he exulted. And if he was as great as all that, it could not be that his position was hopeless. Time and again Carl Carroll, the Boy Detective, had been in equally precarious positions, but in the end he had brought the Pale Avengers low. And what a boy, untrained, could do, a graduate of the Rising Sun Correspondence School of Detecting ought to be able to do! He drew his knife from his pocket and cut into the wall-paper of the side wall.

Being a paper-hanger, the first touch of his hand against the side wall had told him the wall-paper was pasted on canvas and not on a solid wall, and now he ripped the canvas away. The wall was of rough boards, scarred and marred. The opposite wall was the same. He kneeled on the bed and tried the rear wall. He felt the plastered wall gliding upward. He stood on the bed and ripped the canvas ceiling away.

As he ripped the ceiling away, light entered the cage from a dirty skylight far above. Just over his head a heavy iron grating covered the cage, barring him in, but high up he could see the great drum, from which the cable slowly unwound as the car descended. He was in an elevator, but this knowledge gave him small comfort. Cage, room, or elevator—call it what he chose—it was relentlessly descending into the flooded cellar. He watched the drum with fascinated eyes, as the wire cable unwound itself. He lay back on the bed, his feet hanging to the floor, and stared upward. He could not take his eyes from the revolving drum. It was like a clock, marking the moments he still had to live.

But suddenly he was galvanized into action. Over his feet something cold ran, making him jerk them from the floor. It was the water of the oubliette, and he gazed on it with horror as it rose, inch by inch, toward him. Slowly, as the car dropped, the water crept up. It reached the first drawer of the small bureau. It crept up to the side rails of the bed. It wet the mattress—and still it rose. He stood on the bed and grasped the iron grating above his head.

“Stop!” whispered a voice above his head, and the creaking cage stopped.

“Gubb! Detective Gubb!” whispered the voice, and Philo Gubb looked upward. “Listen, Detective Gubb,” said the voice. “One touch of my hand on the lever, and you will be dropped beneath the waters, never to appear again, except dead. One only chance remains for your life, and, blackened with crime though we are, we offer you that chance. If you will swear to leave the State, never to return, we will spare you. What say you, Philo Gubb?”

It was an offer no mortal could refuse. Life, after all, is sweet. Philo Gubb, the relentless Correspondence School detective, opened his mouth, but as he turned his head upward, he closed it again and licked his lips twice.

“No, durn ye!” he shouted angrily. “I won’t never do no such thing!”

There was a hurried whispering of many voices above him.

“Think well,” said the voice again. “We will give you until midnight to reconsider your rashness. Until midnight, Detective Gubb!”

“You can’t scare me!” shouted Philo Gubb.

“Until midnight!” repeated the voice, and then there was silence.

Philo Gubb immediately drew his heavy pocket-knife from his pocket and began cutting out one of the panels of the door that shut him in on one side. He did not work hurriedly. He was not at all frightened. Looking up, he had seen the drum, and there was no more cable on the drum to be unwound. The car could descend no farther. His feet were as wet as they could get. Unless the river rose to unbelievable height, he could not be drowned in the makeshift oubliette, unless he voluntarily lay down in the shallow water and inhaled it. He worked on the panel slowly, but with the earnestness of a very angry victim of a hoax. The panel fell outward with a splash, and floated away. Philo Gubb bent sideways and squeezed out of the small opening into the cellar.

The huge cellar was dusky in the dim light that entered through the cobwebbed panes, high in the wall. It was an immense place, and now knee-deep in water, except for a gangway of boards laid on low trestles, which led from one side of the cellar to the cellar door. There were coal-bins and vegetable-bins, like watery bays leading from the general cellar sea, and—strange appliance to discover in a hotel cellar—a small hay-baling press stood on an extemporized platform against one wall, and alongside it, on a long table, such as are seen in factories, bales of hay, some complete and some torn open—and cases! The cases were labeled “Blue River Canned Tomatoes,” but one, split across the end, gave evidence that their contents were not canned tomatoes at all. Through the crack in the case glittered the six silver stars of the Six Star whiskey. There were twenty-six of the cases.

Philo Gubb waded to the raised gangway and walked to the cellar door. It was double-barred on the inside, and he lifted the bars cautiously and stepped into the alley, closing the door carefully behind him. He pulled his false whiskers and wig from his face and stuffed them in his pockets and hurried down the alley.

When he returned, Billy Getz, Jack Harburger, and six of the Kidders were holding high revel in the closed bar-room of the Harburger House, but they all fell silent when the door opened and the Sheriff of Derling County entered, with Philo Gubb and three deputies in company. It was evident that the Sheriff did not consider Philo Gubb a joke.

“Search-warrant, Jack,” he said to Harburger. “Detective Gubb, of Riverbank, has been doing some sleuthing in your hotel, he says. We want to have a look at the cellar.”

The next morning the “Riverbank Eagle” was full of Philo Gubb again. Through the superb acumen of that wonderful detective, three stores of whiskey had been discovered and confiscated—one in the cellar of the Harburger House at Derlingport; one in Joe Henry’s stable at Riverbank; and a smaller one in the room in the Willcox Building frequented by the “Kidders.”

“How I done it?” said Philo Gubb to one of his admirers. “I done it like a deteckative does it—a deteckative that wants to detect—picks up some feller that looks suspicious-like, like it says in Lesson Four, Rule Four. And then he shadows and trails him, like it says in Lesson Four, Rules Four to Seventeen. And then somethin’s bound to happen.”

“But how can you tell what’s goin’ to happen?” asked his admirer.

“Well, sir,” said Philo Gubb, “that’s the beauty of the deteckative business. You don’t ever know what’s goin’ to happen until it happens.”