Anthony Payne, the “Falstaff of the West,” was born in the manor house, Strat-ton, the son of a tenant farmer, under the Grenvilles of Stowe. The registers do not go back sufficiently far to record the date of his birth. The Tree Inn is the ancient manor house in which the giant first saw the light. He rapidly shot up to preternatural size and strength. So vast were his proportions as a boy, that his schoolmates were accustomed to work out their arithmetic lessons in chalk on his back, and sometimes even thereon to delineate a map of the world, so that he might return home, like Atlas, carrying the world on his shoulders for his father with a stick to dust out.

It was his delight to tuck two urchins under his arms, one on each side, and climb, so encumbered with “his kittens,” as he called them, to a height over-hanging the sea, to their infinite terror, and this he would call “showing them the world.” A proverb still extant in Cornwall, expressive of some unusual length, is “As long as Tony Payne’s foot.”

At the age of twenty-one he was taken into the establishment at Stowe. He then measured seven feet two inches in height without his shoes, and he afterwards grew two inches higher. He was not tall and lanky, but stout and well propor-tioned in every way. The original mansion of the Grenvilles at Stowe still in part remains as a farmhouse. The splendid house of Stowe, built by the first Earl of Bath, was pulled down shortly after 1711, and it was said that men lived who had seen the stately palace raised and also levelled with the dust. This was at a little distance further inland than the old Stowe that remains. The Grenvilles had also a picturesque house at Broom Hill, near Bude, with fine Elizabethan plaster-work ceilings, now converted into labourers’ cottages.

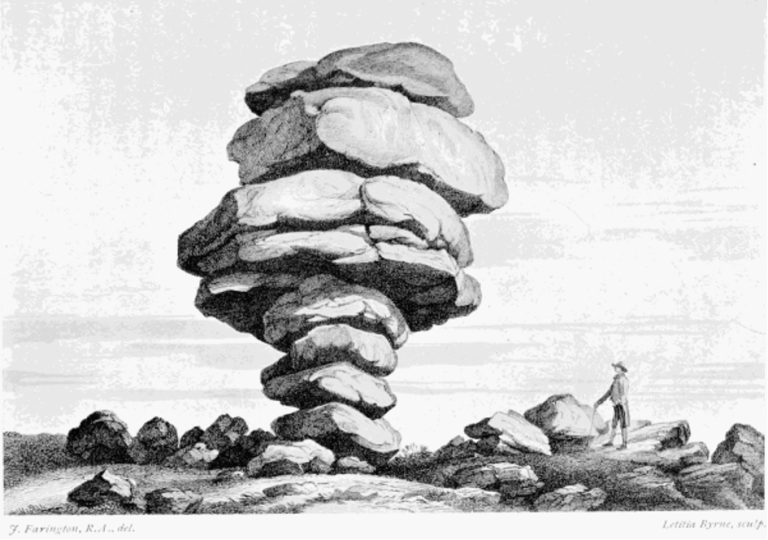

At Stowe Anthony Payne delighted in exhibiting his strength. In the hurling-ground a rough block of stone is still pointed out as “Payne’s cast,” lying full ten paces beyond the reach whereat the ordinary player could “put the stone.”

It is said that one Christmas Eve the fire languished in the hall. A boy with an ass had been sent into the wood for faggots. Payne went to hurry him back, and caught up the ass and his burden, flung them over his shoulder, and brought both into the hall and cast them down by the side of the fire.

On another occasion, being defied to perform the feat, he carried a bacon-hog from Kilkhampton to Stowe. Then came the Civil War, when Charles I and his Parliament sought to settle their differences on the battlefield. Cornwall went for the King, and Anthony Payne had the drilling and manœuvring of the rec-ruits from Kilkhampton and Stratton. At one time Sir Beville Grenville had his head-quarters at Truro, but the great battle of Stamford Hill, May 16th, 1643, was fought but eight miles from Stowe, and on the night preceding it Sir Be-ville Grenville slept in his house at Broom Hill. The battle was desperate, the Royalist soldiers being outnumbered, and attacked; amidst them was Anthony Payne, mounted on his sturdy cob Samson, rallying his troopers and terrorizing the enemy, who fled. At the next pitched battle at Lansdown, near Bath, the forces of the King were defeated and Sir Beville was killed. Anthony Pay-ne, having mounted John Grenville, then a youth of sixteen, on his father’s hor-se, had led on the Grenville troops to the fight. The Rev. R. S. Hawker gives a letter from the giant to Lady Grace Grenville, conveying to her the news of the death of her husband; but it is more than doubtful whether this be genuine. He says of it: “It still survives. It breathes, in the quaint language of the day, a nob-le strain of sympathy and homage.” It does not exist except in Mr. Hawker’s book, and is almost certainly a fabrication by him.

At the Restoration, Sir John Grenville was created Earl of Bath, and was made governor of the garrison of Plymouth, and he then appointed Payne halberdier of the guns. The King, who held Payne in great favour, made him a yeoman of his guards, and Sir Godfrey Kneller, the Court artist, was employed to paint his portrait.

Whilst in Plymouth garrison an incident occurred that has been recorded by Hawker. At the mess-table of the regiment, during the reign of William and Mary, on the anniversary of the day when Charles I had been beheaded, a sub-officer of Payne’s own rank had ordered a calf’s head to be served up. This was a coarse and common annual mockery of the beheaded king indulged in by the remnants of the old fanatical Puritan party. When Payne entered the room his comrades pointed out the dish to him. Anthony flared up, and flung the plate and its contents out of the window. A quarrel and a challenge ensued, and at break of day Payne and his antagonist fought with swords on the ramparts, and Anthony ran the offender through the swordarm and disabled him, as he shouted, “There’s sauce for thy calf’s head.”

Hawker, who tells the story, supposed that the incident occurred during the re-ign of George I. But Anthony died at an age little short of eighty, and was bu-ried at Stratton July 13th, 1691, and William of Orange did not die till 1702.

After his death at Stratton, which took place in the house where he was born, neither door nor stairs would afford egress for the large coffined corpse. The joists had to be sawn through, and the floor lowered with rope and pulley, to enable the giant to pass out to his last resting-place, under the south wall of Stratton Church.[12]

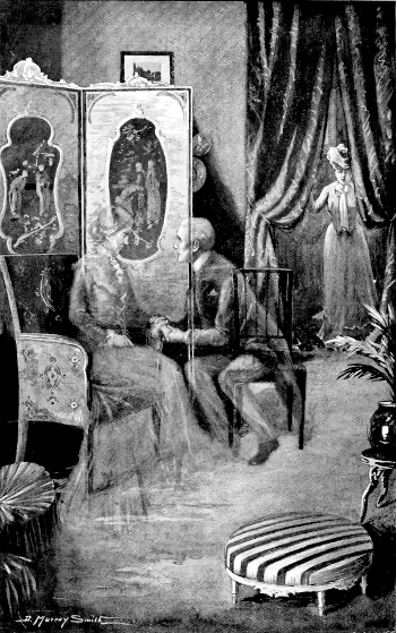

The history of the vicissitudes through which went the painting by Kneller is peculiarly interesting.

When Stowe was dismantled, on the death of the Earl of Bath, the picture was removed to Penheale, another Cornish residence of the Grenville family.

But here the portrait of him who had done so much for the house was not va-lued, and was soon forgotten. Gilbert, the Cornish historian, in one of his rambles, whilst staying at an old inn in Launceston, was informed that this pa-inting was still extant, and he went to Penheale, where the farmer’s wife oc-cupying the house said that she did indeed possess “a carpet with the effigy of a large man on it,” that had been given to her husband by the steward on the esta-te. It was rolled up, and in a bad and dirty condition. She gladly sold it to C. S. Gilbert for £8. On Gilbert’s death his effects were sold at Devonport, and a stranger bought it for £42. In London it was recognized as the work of Kneller, and was resold for the sum of £800. It next appeared amongst the effects of the late Admiral Tucker, at Trematon Castle; and when the sale took place this picture was bought by a gentleman in Devon. Finally Mr. (now Sir) Robert Harvey purchased it, and most generously presented it to the Royal Institution of Cornwall.

The authorities for Anthony Payne are Hawker’s Footprints of Former Men in Cornwall; the Journal of the R. Inst. of Cornwall, Vol. X, 1890-1; Wood (E. J.), Giants and Dwarfs, 1868.

Next in size to Anthony Payne among big Cornishmen was Charles Chilcott, of Tintagel, who measured 6 feet 4 inches high, and round the breast 6 feet 9 inc-hes, and who weighed 460 pounds. He was almost constantly occupied in smo-king, three pounds of tobacco being his weekly allowance. His pipe was two inches long. One of his stockings would contain six gallons of wheat. He was much gratified when strangers came to visit him, and to them his usual address was, “Come under my arm, little fellow.” He died in his sixtieth year, 5th Ap-ril, 1815.