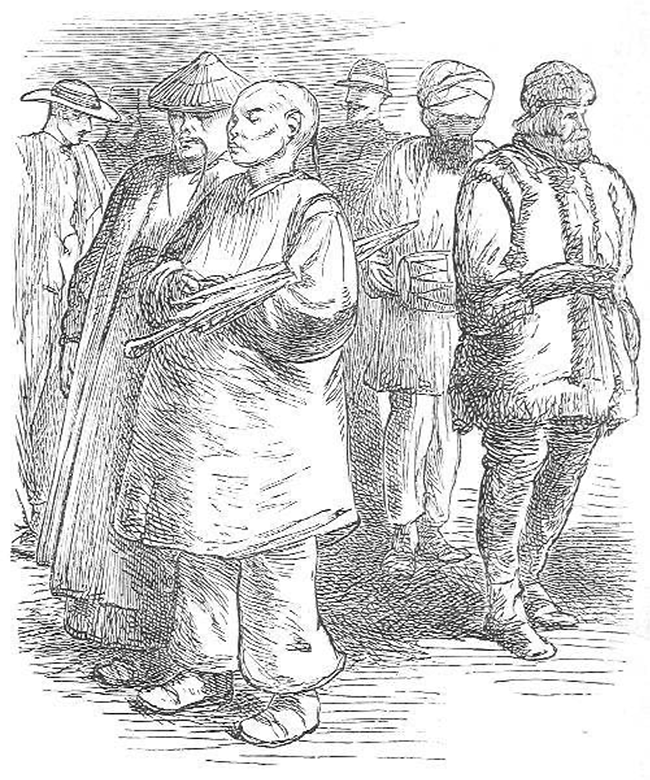

“HARRY was a hero, if ever there was one!” cried Theodore Vassy, after he had been for some time silently looking at a print of the prince who was afterwards so famous as Henry V. The print represented the well-known anecdote of Harry’s trying on the crown of England by the sick-bed of his father.

“I never admire that story much,” observed Theodore’s eldest sister Alice, raising her eyes from a volume which she had been reading. “A son finds, as he thinks, that his father has just died; and, instead of bursting into tears (like our good Queen when she gained a throne by the death of her uncle), Prince Harry’s first thought is to try on the crown! I do not wonder,” added Alice with a smile, “that when the poor sick king woke from his deathlike sleep, he was little pleased with his son.”

“But the son, if the story be true, made such a noble excuse for him-self, that even his father was satisfied,” said Theodore. “Harry had not tried on the crown because he was in the least hurry to wear it, but be-cause—”

Alice shook her head, laughing. “Harry’s excuses may have been clever, but I am afraid that they were but false ones,” said she; “for when he was once on the throne, one crown was not enough for King Harry: he must carry sword and fire into poor France, because he wanted to have two!”

“Girls know nothing, understand nothing, about heroes,” said Theodore in a tone of contempt.

“Girls have been heroines,” replied Alice with some animation. “In this very book which I have been reading—’Memorials of Agnes Jones’—there is an anecdote of her courage when she was a child of but eight years old which might have done credit to a boy of ten, even if he bore the name of Theodore Vassy,” added the elder sister gaily.

Theodore prided himself on his manly spirit, though it was a spirit which more often carried him into difficulties than bore him bravely through them. For instance, Theodore had boasted that he would clear his fat-her’s cellar of the troublesome rats that had made it their home; and he had made an attempt to do so. The boy had even succeeded in catching a rat by the tail! But no sooner had the fierce little prisoner turned and bit his captor’s finger, than Theodore, giving a cry of pain, had let the rat go, and had retreated at once from the cellar, leaving the honours of the battle-field to his small four footed foe.

Luckily for Theodore, no one had been present to witness the fight; and the boy took good care not to mention his adventure. Not even Alice knew where her brother had got the little mark left on his hand by the teeth of the rat.

“Let’s hear your anecdote, if it’s worth the hearing,” said Theodore Vassy. “I never yet knew a girl who would not cry at the prick of a need-le.”

Alice turned back the pages of the book which she had been reading, till she came to the part relating to the childhood of Agnes Jones.

“This memoir is written by the sister of Agnes,” observed Alice; “and it is one of the most beautiful books which I ever read in my life.”

“And who was this Agnes?” asked Theodore.

“A young lady, the daughter of an officer,” replied Alice Vassy. “When she was a little child, she accompanied her parents to the island of Ma-uritius, off the east coast of Africa, where occurred the following inci-dent, thus related by her sister.” And Alice read as follows:—

“At Mauritius, when she was about eight years old, a friend sent her a present of a young kangaroo from Australia. An enclosure was made for it in the garden, and Agnes delighted to feed and visit it daily.”

“I’ve seen a kangaroo in the Zoological Gardens,” interrupted Theodore. “It was larger than our big dog, and went springing and jumping on its long hind legs, as if it were set on springs. I never saw such a creature for leaping! I was told that the kangaroo has tremendous strength in those hind legs, and that, when hunted, it makes itself dangerous even to the dogs. I suppose that this little girl’s kangaroo was very tame as well as young, or she might have had more pain than pleasure from her plaything.” Theodore was thinking of his fight with the rat.

Alice went on reading the sister’s account of the little Agnes and her pet kangaroo:—

“One day, as she opened the gate, it escaped, and bounded off into our neighbour’s plantation. Agnes followed, fearing it might do mischief, climbed over the low wall which separated the two gardens, and after a long chase succeeded in capturing the fugitive. Some minutes af-terwards my mother came into the garden, and was horror-struck to see her returning from the pursuit—the kangaroo, which she held bra-vely by its ears, struggling wildly for freedom, and tearing at her with its hind feet; while her dress was streaming with blood from the wounds inflicted by its nails.”

“I say!” exclaimed Theodore involuntarily, “I’d have let the horrid beast go!”

“But she would not do so,” continued Alice, still reading, “until she got it safely into its house; although it was many a long day before she lost the marks of her battle and its victory.”

“She was a gallant little soul!” exclaimed Theodore. “What a pity it is that Agnes was a girl, and not a boy! For, after all, courage is not of much use to a woman.”

“I am not sure of that,” replied Alice; “nor, perhaps, would you think so, were you to read this beautiful Life. Agnes left a bright, happy home, to watch as a nurse by the sick-beds of the poor. Though she was a lady born and bred, she shrank from no drudgery, grumbled at no hardship: she worked hard, and she worked cheerfully, looking for no reward upon earth. Agnes had to struggle against great difficulties; but she mastered them just as she had mastered the kangaroo when she was a child.”

“And got nothing by it,” said Theodore Vassy. “One might suffer, and struggle, and conquer difficulties, if, like Harry the Fifth, one had a crown to make it worth while.”

“There was a crown for Agnes,” observed Alice gravely; “but not one that man could give, or that she could wear upon earth. The artist who drew that picture—” Alice glanced as she spoke at the print in the hand of her brother—”has made Prince Henry look upwards, as if praying to be made worthy to have a crown. Agnes Jones’s was a life-long looking upwards—a life-long trying on, as it were, of the crown prepared for such as love their Heavenly King;—and I believe,” added Alice, as she closed her volume, “that after her brave struggles and her victories, Agnes Jones has gone to wear that crown.”