Much has been written about Dolly Pentreath, but little is known of her uneventful life. That little may be summed up in few words.

Her maiden name was Jeffery, and when she was a child her parents and all about her spoke the Cornish language. Drew, in his History of Cornwall, quoting Daines Barrington, says: “She does indeed talk Cornish as readily as others do English, being bred up from a child to know no other language; nor could she (if we may believe her) talk a word of English before she was past twenty years of age.”

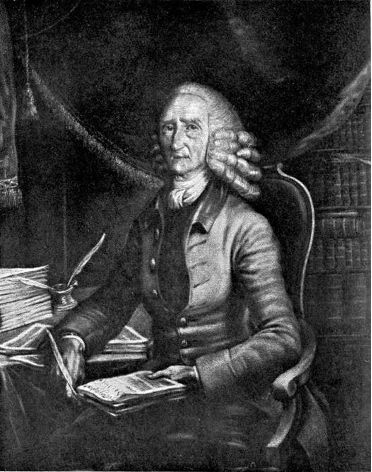

In the year 1768 the Hon. Daines Barrington, brother of Captain, afterwards Admiral, Barrington, went into Cornwall to ascertain whether the Cornish language had entirely ceased to be spoken, or not, and in a letter written to John Lloyd, F.S.A., a few years after, viz. on March 31, 1773, he gives the following as the result of his journey:—

“I set out from Penzance, with the landlord of the principal inn for my guide, towards Sennen, or the most western point; and when I approached the village I said that there must probably be some remains of the language in those parts if anywhere, as the village was in the road to no place whatever, and the only ale-house announced itself to be the last in England.

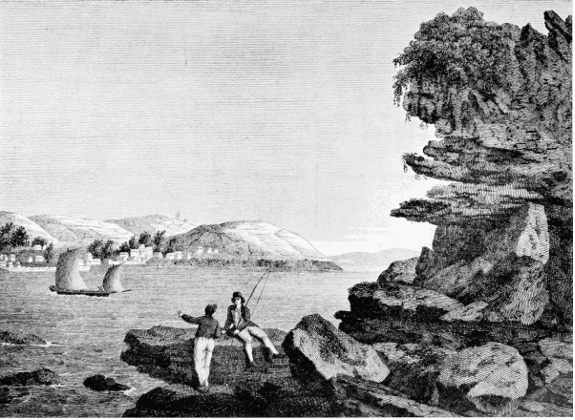

“My guide, however, told me that I should be disappointed, but that if I would ride about ten miles about on my return to Penzance he would conduct me to a village called Mousehole, on the western side of Mount’s Bay, where there was an old woman, called Dolly Pentreath, who could speak Cornish fluently. While we were travelling together towards Mousehole I inquired how he knew that this woman spoke Cornish; when he informed me that he frequently went from Penzance to Mousehole to buy fish, which were sold by her; and that when he did not offer her a price that was satisfactory, she grumbled to some other old women in an unknown tongue, which he concluded, therefore, to be Cornish.

“When we reached Mousehole I desired to be introduced as a person who had laid a wager that there was not one who could converse in Cornish; upon which Dolly Pentreath spoke in an angry tone for two or three minutes, and in a language which sounded very like Welsh. The hut in which she lived was in a very narrow lane, opposite to two rather better houses, at the doors of which two other women stood, who were advanced in years, and who I observed were laughing at what Dolly said to me.

“Upon this I asked them whether she had not been abusing me; to which they answered, ‘Very heartily,’ and because I had supposed she could not speak Cornish.

“I then said that they must be able to talk the language; to which they answered that they could not speak it readily, but that they understood it, being only ten or twelve years younger than Dolly Pentreath.

“I continued nine or ten days in Cornwall after this, but found that my friends whom I had left to the eastward continued as incredulous almost as they were before about these last remains of the Cornish language, because, among other reasons, Dr. Borlase had supposed, in his Natural History of the County, that it had entirely ceased to be spoken. It was also urged that, as he lived within four or five miles of the old woman at Mousehole, he consequently must have heard of so singular a thing as her continuing to use the vernacular tongue.

“I had scarcely said or thought anything more about this matter till last summer (1772), having mentioned it to some Cornish people, I found that they could not credit that any person had existed within these few years who could speak their native language; and therefore, though I imagined there was but a small chance of Dolly Pentreath continuing to live, yet I wrote to the President, then in Devonshire, to desire that he would make some inquiry with regard to her; and he was so obliging as to procure me information from a gentleman whose house was within three miles of Mousehole, a considerable part of whose letter I subjoin.

“’Dolly Pentreath is short of stature, and bends very much with old age, being in her eighty-seventh year, so lusty, however, as to walk hither to Castle Horneck, about three miles, in bad weather, in the morning and back again. She is somewhat deaf, but her intellect seemingly not impaired; has a memory so good, that she remembers perfectly well, that about four or five years ago at Mousehole, where she lives, she was sent for by a gentleman, who, being a stranger, had a curiosity to hear the Cornish language, which she was famed for retaining and speaking fluently, and that the innkeeper where the gentleman came from attended him.

(“This gentleman,” says Daines Barrington, “was myself; however, I did not presume to send for her, but waited upon her.”)

“’She does, indeed, talk Cornish as readily as others do English, being bred up from a child to know no other language; nor could she (if we may believe her) talk a word of English before she was past twenty years of age, as, her father being a fisherman, she was sent with fish to Penzance at twelve years old, and sold them in the Cornish language, which the inhabitants in general, even the gentry, did then well understand. She is positive, however, that there is neither in Mousehole, nor in any other part of the county, any other person who knows anything of it, or, at least, can converse in it. She is poor, and maintained partly by the parish, and partly by fortune-telling and gabbling Cornish.’

“I have thus,” continued Mr. Barrington, “thought it right to lay before the Society (the Society of Antiquaries) this account of the last sparks of the Cornish tongue, and cannot but think that a linguist who understands Welsh might still pick up a more complete vocabulary of the Cornish than we are yet possessed of, especially as the two neighbours of this old woman (Dolly Pentreath), whom I had occasion to mention, are not now above seventy-seven or seventy-eight years of age, and were healthy when I saw them; so that the whole does not depend on the life of this Cornish sybil, as she is willing to insinuate.”

It is matter of profound regret that no Welshman did visit Dolly, who lived for four years after Mr. Barrington’s letter, which was written in 1773, for she died December 26th, 1777.

Drew says: “She was buried in the churchyard of the parish of Paul, in which parish, Mousehole, the place of her residence, is situated. Her epitaph is both in Cornish and English.”

Coth Doll Pentreath cans ha Deau;Marow ha kledyz ed Paul plêa:—Na ed an Egloz, gan pobel brâs,Bes ed Egloz-hay coth Dolly es.

Old Doll Pentreath, one hundred aged and two,Deceased, and buried in Paul parish too:—Not in the Church, with people great and high,But in the Churchyard doth old Dolly lie!

This epitaph, written by Mr. Tomson, of Truro, was never inscribed on her tombstone, for no tombstone was set up to her memory at the time of her death. The stone now erected, and standing in the churchyard wall and not near her grave, was set up by Prince Louis Lucien Bonaparte in 1860, and contains two errors. It runs: “Here lieth interred Dorothy Pentreath, who died in 1778.” In the first place she does not lie where is the stone, and in the second place she died 1777, on December 26th, and was buried on the following day.

In 1776 Mr. Barrington presented a letter to the Royal Society of Antiquaries written in Cornish and in English, by William Bodener, a fisherman of Mousehole. This man asserted that at that date there were still four or five persons in Mousehole who could talk Cornish.

In 1777, the year of Dolly’s death, Mr. Barrington found another Cornishman named John Nancarrow, of Marazion, aged forty-five years, able to speak Cornish. John Nancarrow said that “in his youth he had learned the language from the country people, and could thus hold a conversation in it; and that another, a native of Truro, was at that time also acquainted with the Cornish language, and like himself was able to converse in it.”

This last is supposed to be the Mr. Tomson who wrote the epitaph for Dolly Pentreath which was never set up.

In Hitchens’ and Drew’s History of Cornwall, it is said: “The Cornish language was current in a part of the South Hams in the time of Edward I (1272-1307). Long after this it was common on the banks of the Tamar, and in Cornwall it was universally spoken.

“But it was not till towards the conclusion of the reign of Henry VIII (1509-47) that the English language had found its way into any of the Cornish churches. Before this time the Cornish language was the established vehicle of communication.

“Dr. Moreman, a native of Southill, but vicar of Menheniot, was the first who taught the inhabitants of this parish the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed, and the Ten Commandments in the English tongue; and this was not done till just about the time that Henry VIII closed his reign. From this fact one inference is obvious, which is, that if the inhabitants of Menheniot knew nothing more of the English than what was thus learnt from the vicar of the parish, the Cornish must have prevailed among them at that time … and as the English language in its progress travelled from east to west, we may reasonably conclude that about this time it had not penetrated far into the county, as Menheniot lies towards its eastern quarter.

“From the time the liturgy was established in the Cornish churches in the English language, the Cornish tongue rapidly declined.

“Hence Mr. Carew, who published his Survey of Cornwall in 1602, notices the almost total extirpation of the language in his days. He says, ‘The principal love and knowledge of this language liveth in Dr. Kennall the civilian, and with him lyeth buried; for the English speech doth still encroach upon it and hath driven the same into the uttermost skirts of the shire. Most of the inhabitants can speak no word of Cornish; but few are ignorant of the English; and yet some so affect their airs, as to a stranger they will not speak it; for if meeting them by chance you inquire the way, or any such matter, your answer shall be, “Meea naurdua cowzasourzneck?” (I can speak no Saxonage).’

“Carew’s Survey was soon followed by that of Norden, by whom we are informed that the Cornish language was chiefly confined to the western hundreds of the county, particularly to Penwith and Kirrier, and yet (which is to be marveyled) though the husband and wife, parents and children, masters and servants, etc., naturally communicate in their native language, yet there is none of them in a manner but is able to converse with a stranger in the English tongue, unless it be some obscure people who seldom confer with the better sort. But it seemeth, however, that in a few years the Cornish will be by little and little abandoned.”

The Cornish was, however, so well spoken in the parish of Feock by the old inhabitants till about the year 1640, “that Mr. William Jackman, the then vicar, and chaplain also of Pendennis Castle, at the siege thereof by the Parliament army, was forced for divers years to administer the sacrament to the communicants in the Cornish tongue, because the aged people did not well understand the English, as he himself often told me,” says Hals.

So late as 1650 the Cornish language was currently spoken in the parishes of Paul and S. Just; the fisherwomen and market-women in the former, and the tinner in the latter, for the most part conversing in their old vernacular tongue; and Mr. Scawen says that in 1678 the Rev. F. Robinson, rector of Landewednack, “preached a sermon to his parishioners in the Cornish language only.”

Had the Bible been translated, had even the English Prayer-book been rendered into Cornish, the language would have lived on. It is due to a large extent to this—the translation into Welsh—that in Wales their ancient language has maintained itself.

The editors of the Bibliotheca Cornubiensis state that Dorothy Jeffery, daughter of Nicolas Pentreath, was baptized at Paul 17th May, 1714; and they conclude that she was the Dolly Pentreath who died in 1777, and that her age accordingly was sixty-three and not one hundred and two.

But this is a mistake. Dolly was a Jeffery by birth and married a Pentreath.

A story is told of Dolly in Mr. J. Henry Harris’s Cornish Saints and Sinners, “as current in Mousehole, but whether true or well conceived it is not possible for me to say.”

It is to this effect: that on one occasion a deserter from a man-of-war fled to her house for refuge, and as there was a cavity in her chimney large enough to contain a man, she thrust him into it, and threw a bundle of dry furze on the fire, and filled the crock with water. Into the middle of the kitchen she drew a “keeve,” which she used for washing, and when the naval officer and his men in pursuit burst into her house, Dolly was sitting on a stool, her legs bare and her feet ready to be immersed in the keeve. She screamed out on their entry that she was about to wash her feet, and only waiting for the water to get hot enough. The officer persisted in searching, and she gave tongue in strong and forcible Cornish. She rushed to the door and screamed to the good people of Mousehole, that the lieutenant and his men had invaded her house without leave, and were impudent and audacious enough to ransack every other cottage in the place. The officer and his men withdrew without having seen and secured their man; and that night a fishing lugger stole out of Mousehole with the deserter on board and made for Guernsey, which in those days was a sort of dumping-ground for all kinds of rascals who were “wanted” at home.