In the Land’s End district is the little church-town of Zennor. There is no village to speak of—a few scattered farms, and here and there a cluster of cottages. The district is bleak, the soil does not lie deep over granite that peers through the surface on exposed spots, where the furious gales from the ocean sweep the land. If trees ever existed there, they have been swept away by the blast, but the golden furze or gorse defies all winds, and clothes the moorland with a robe of splendour, and the heather flushes the slopes with crimson towards the decline of summer, and mantles them in soft, warm brown in winter, like the fur of an animal.

In Zennor is a little church, built of granite, rude and simple of construction, crouching low, to avoid the gales, but with a tower that has defied the winds and the lashing rains, because wholly devoid of sculptured detail, which would have afforded the blasts something to lay hold of and eat away. In Zennor parish is one of the finest cromlechs in Cornwall, a huge slab of unwrought stone like a table, poised on the points of standing upright blocks as rude as the mass they sustain.

Near this monument of a hoar and indeed unknown antiquity lived an old woman by herself, in a small cottage of one story in height, built of moor stones set in earth, and pointed only with lime. It was thatched with heather, and possessed but a single chimney that rose but little above the apex of the roof, and had two slates set on the top to protect the rising smoke from being blown down the chimney into the cottage when the wind was from the west or from the east. When, however, it drove from north or south, then the smoke must take care of itself. On such occasions it was wont to find its way out of the door, and little or none went up the chimney.

The only fuel burnt in this cottage was peat—not the solid black peat from deep bogs, but turf of only a spade graft, taken from the surface, and composed of undissolved roots. Such fuel gives flame, which the other does not; but, on the other hand, it does not throw out the same amount of heat, nor does it last one half the time.

The woman who lived in the cottage was called by the people of the neighbourhood Aunt Joanna. What her family name was but few remembered, nor did it concern herself much. She had no relations at all, with the exception of a grand-niece, who was married to a small tradesman, a wheelwright near the church. But Joanna and her great-niece were not on speaking terms. The girl had mortally offended the old woman by going to a dance at St. Ives, against her express orders. It was at this dance that she had met the wheelwright, and this meeting, and the treatment the girl had met with from her aunt for having gone to it, had led to the marriage. For Aunt Joanna was very strict in her Wesleyanism, and bitterly hostile to all such carnal amusements as dancing and play-acting. Of the latter there was none in that wild west Cornish district, and no temptation ever afforded by a strolling company setting up its booth within reach of Zennor. But dancing, though denounced, still drew the more independent spirits together. Rose Penaluna had been with her great-aunt after her mother’s death. She was a lively girl, and when she heard of a dance at St. Ives, and had been asked to go to it, although forbidden by Aunt Joanna, she stole from the cottage at night, and found her way to St. Ives.

Her conduct was reprehensible certainly. But that of Aunt Joanna was even more so, for when she discovered that the girl had left the house she barred her door, and refused to allow Rose to re-enter it. The poor girl had been obliged to take refuge the same night at the nearest farm and sleep in an outhouse, and next morning to go into St. Ives and entreat an acquaintance to take her in till she could enter into service. Into service she did not go, for when Abraham Hext, the carpenter, heard how she had been treated, he at once proposed, and in three weeks married her. Since then no communication had taken place between the old woman and her grand-niece. As Rose knew, Joanna was implacable in her resentments, and considered that she had been acting aright in what she had done.

The nearest farm to Aunt Joanna’s cottage was occupied by the Hockins. One day Elizabeth, the farmer’s wife, saw the old woman outside the cottage as she was herself returning from market; and, noticing how bent and feeble Joanna was, she halted, and talked to her, and gave her good advice.

“See you now, auntie, you’m gettin’ old and crimmed wi’ rheumatics. How can you get about? An’ there’s no knowin’ but you might be took bad in the night. You ought to have some little lass wi’ you to mind you.”

“I don’t want nobody, thank the Lord.”

“Not just now, auntie, but suppose any chance ill-luck were to come on you. And then, in the bad weather, you’m not fit to go abroad after the turves, and you can’t get all you want—tay and sugar and milk for yourself now. It would be handy to have a little maid by you.”

“Who should I have?” asked Joanna.

“Well, now, you couldn’t do better than take little Mary, Rose Hext’s eldest girl. She’s a handy maid, and bright and pleasant to speak to.”

“No,” answered the old woman, “I’ll have none o’ they Hexts, not I. The Lord is agin Rose and all her family, I know it. I’ll have none of them.”

“But, auntie, you must be nigh on ninety.”

“I be ower that. But what o’ that? Didn’t Sarah, the wife of Abraham, live to an hundred and seven and twenty years, and that in spite of him worritin’ of her wi’ that owdacious maid of hern, Hagar? If it hadn’t been for their goings on, of Abraham and Hagar, it’s my belief that she’d ha’ held on to a hundred and fifty-seven. I thank the Lord I’ve never had no man to worrit me. So why I shouldn’t equal Sarah’s life I don’t see.”

Then she went indoors and shut the door.

After that a week elapsed without Mrs. Hockin seeing the old woman. She passed the cottage, but no Joanna was about. The door was not open, and usually it was. Elizabeth spoke about this to her husband. “Jabez,” said she, “I don’t like the looks o’ this; I’ve kept my eye open, and there be no Auntie Joanna hoppin’ about. Whativer can be up? It’s my opinion us ought to go and see.”

“Well, I’ve naught on my hands now,” said the farmer, “so I reckon we will go.”

The two walked together to the cottage. No smoke issued from the chimney, and the door was shut. Jabez knocked, but there came no answer; so he entered, followed by his wife.

There was in the cottage but the kitchen, with one bedroom at the side. The hearth was cold.

“There’s some’ut up,” said Mrs. Hockin.

“I reckon it’s the old lady be down,” replied her husband, and, throwing open the bedroom door, he said: “Sure enough, and no mistake—there her be, dead as a dried pilchard.”

And in fact Auntie Joanna had died in the night, after having so confidently affirmed her conviction that she would live to the age of a hundred and twenty-seven.

“Whativer shall we do?” asked Mrs. Hockin.

“I reckon,” said her husband, “us had better take an inventory of what is here, lest wicked rascals come in and steal anything and everything.”

“Folks bain’t so bad as that, and a corpse in the house,” observed Mrs. Hockin.

“Don’t be sure o’ that—these be terrible wicked times,” said the husband. “And I sez, sez I, no harm is done in seein’ what the old creetur had got.”

“Well, surely,” acquiesced Elizabeth, “there is no harm in that.”

In the bedroom was an old oak chest, and this the farmer and his wife opened. To their surprise they found in it a silver teapot, and half a dozen silver spoons.

“Well, now,” exclaimed Elizabeth Hockin, “fancy her havin’ these—and me only Britannia metal.”

“I reckon she came of a good family,” said Jabez. “Leastwise, I’ve heard as how she were once well off.”

“And look here!” exclaimed Elizabeth, “there’s fine and beautiful linen underneath—sheets and pillow-cases.”

“But look here!” cried Jabez, “blessed if the taypot bain’t chock-full o’ money! Whereiver did she get it from?”

“Her’s been in the way of showing folk the Zennor Quoit, visitors from St. Ives and Penzance, and she’s had scores o’ shillings that way.”

“Lord!” exclaimed Jabez. “I wish she’d left it to me, and I could buy a cow; I want another cruel bad.”

“Ay, we do, terrible,” said Elizabeth. “But just look to her bed, what torn and wretched linen be on that—and here these fine bedclothes all in the chest.”

“Who’ll get the silver taypot and spoons, and the money?” inquired Jabez.

“Her had no kin—none but Rose Hext, and her couldn’t abide her. Last words her said to me was that she’d ‘have never naught to do wi’ the Hexts, they and all their belongings.’”

“That was her last words?”

“The very last words her spoke to me—or to anyone.”

“Then,” said Jabez, “I’ll tell ye what, Elizabeth, it’s our moral dooty to abide by the wishes of Aunt Joanna. It never does to go agin what is right. And as her expressed herself that strong, why us, as honest folks, must carry out her wishes, and see that none of all her savings go to them darned and dratted Hexts.”

“But who be they to go to, then?”

“Well—we’ll see. Fust us will have her removed, and provide that her be daycent buried. Them Hexts be in a poor way, and couldn’t afford the expense, and it do seem to me, Elizabeth, as it would be a liberal and a kindly act in us to take all the charges on ourselves. Us is the closest neighbours.”

“Ay—and her have had milk of me these ten or twelve years, and I’ve never charged her a penny, thinking her couldn’t afford it. But her could, her were a-hoardin’ of her money—and not paying me. That were not honest, and what I say is, that I have a right to some of her savin’s, to pay the milk bill—and it’s butter I’ve let her have now and then in a liberal way.”

“Very well, Elizabeth. Fust of all, we’ll take the silver taypot and the spoons wi’ us, to get ‘em out of harm’s way.”

“And I’ll carry the linen sheets and pillow-cases. My word!—why didn’t she use ‘em, instead of them rags?”

All Zennor declared that the Hockins were a most neighbourly and generous couple, when it was known that they took upon themselves to defray the funeral expenses.

Mrs. Hext came to the farm, and said that she was willing to do what she could, but Mrs. Hockin replied: “My good Rose, it’s no good. I seed your aunt when her was ailin’, and nigh on death, and her laid it on me solemn as could be that we was to bury her, and that she’d have nothin’ to do wi’ the Hexts at no price.”

Rose sighed, and went away.

Rose had not expected to receive anything from her aunt. She had never been allowed to look at the treasures in the oak chest. As far as she had been aware, Aunt Joanna had been extremely poor. But she remembered that the old woman had at one time befriended her, and she was ready to forgive the harsh treatment to which she had finally been subjected. In fact, she had repeatedly made overtures to her great-aunt to be reconciled, but these overtures had been always rejected. She was, accordingly, not surprised to learn from Mrs. Hockin that the old woman’s last words had been as reported.

But, although disowned and disinherited, Rose, her husband, and children dressed in black, and were chief mourners at the funeral. Now it had so happened that when it came to the laying out of Aunt Joanna, Mrs. Hockin had looked at the beautiful linen sheets she had found in the oak chest, with the object of furnishing the corpse with one as a winding-sheet. But—she said to herself—it would really be a shame to spoil a pair, and where else could she get such fine and beautiful old linen as was this? So she put the sheets away, and furnished for the purpose a clean but coarse and ragged sheet such as Aunt Joanna had in common use. That was good enough to moulder in the grave. It would be positively sinful, because wasteful, to give up to corruption and the worm such fine white linen as Aunt Joanna had hoarded. The funeral was conducted, otherwise, liberally. Aunt Joanna was given an elm, and not a mean deal board coffin, such as is provided for paupers; and a handsome escutcheon of white metal was put on the lid.

Moreover, plenty of gin was drunk, and cake and cheese eaten at the house, all at the expense of the Hockins. And the conversation among those who attended, and ate and drank, and wiped their eyes, was rather anent the generosity of the Hockins than of the virtues of the departed.

Mr. and Mrs. Hockin heard this, and their hearts swelled within them. Nothing so swells the heart as the consciousness of virtue being recognised. Jabez in an undertone informed a neighbour that he weren’t goin’ to stick at the funeral expenses, not he; he’d have a neat stone erected above the grave with work on it, at twopence a letter. The name and the date of departure of Aunt Joanna, and her age, and two lines of a favourite hymn of his, all about earth being no dwelling-place, heaven being properly her home.

It was not often that Elizabeth Hockin cried, but she did this day; she wept tears of sympathy with the deceased, and happiness at the ovation accorded to herself and her husband. At length, as the short winter day closed in, the last of those who had attended the funeral, and had returned to the farm to recruit and regale after it, departed, and the Hockins were left to themselves.

“It were a beautiful day,” said Jabez.

“Ay,” responded Elizabeth, “and what a sight o’ people came here.”

“This here buryin’ of Aunt Joanna have set us up tremendous in the estimation of the neighbours.”

“I’d like to know who else would ha’ done it for a poor old creetur as is no relation; ay—and one as owed a purty long bill to me for milk and butter through ten or twelve years.”

“Well,” said Jabez, “I’ve allus heard say that a good deed brings its own reward wi’ it—and it’s a fine proverb. I feels it in my insides.”

“P’raps it’s the gin, Jabez.”

“No—it’s virtue. It’s warmer nor gin a long sight. Gin gives a smouldering spark, but a good conscience is a blaze of furze.”

The farm of the Hockins was small, and Hockin looked after his cattle himself. One maid was kept, but no man in the house. All were wont to retire early to bed; neither Hockin nor his wife had literary tastes, and were not disposed to consume much oil, so as to read at night.

During the night, at what time she did not know, Mrs. Hockin awoke with a start, and found that her husband was sitting up in bed listening. There was a moon that night, and no clouds in the sky. The room was full of silver light. Elizabeth Hockin heard a sound of feet in the kitchen, which was immediately under the bedroom of the couple.

“There’s someone about,” she whispered; “go down, Jabez.”

“I wonder, now, who it be. P’raps its Sally.”

“It can’t be Sally—how can it, when she can’t get out o’ her room wi’out passin’ through ours?”

“Run down, Elizabeth, and see.”

“It’s your place to go, Jabez.”

“But if it was a woman—and me in my night-shirt?”

“And, Jabez, if it was a man, a robber—and me in my night-shirt? It ‘ud be shameful.”

“I reckon us had best go down together.”

“We’ll do so—but I hope it’s not——”

“What?”

Mrs. Hockin did not answer. She and her husband crept from bed, and, treading on tiptoe across the room, descended the stair.

There was no door at the bottom, but the staircase was boarded up at the side; it opened into the kitchen.

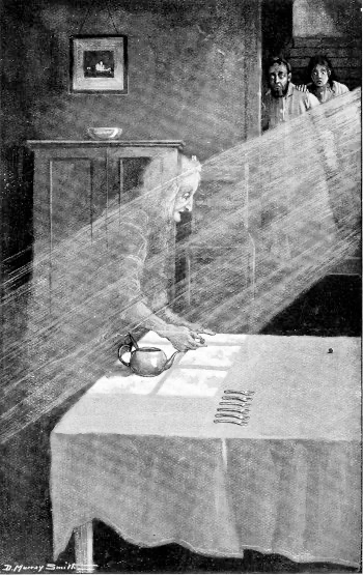

They descended very softly and cautiously, holding each other, and when they reached the bottom, peered timorously into the apartment that served many purposes—kitchen, sitting-room, and dining-place. The moonlight poured in through the broad, low window.

By it they saw a figure. There could be no mistaking it—it was that of Aunt Joanna, clothed in the tattered sheet that Elizabeth Hockin had allowed for her grave-clothes. The old woman had taken one of the fine linen sheets out of the cupboard in which it had been placed, and had spread it over the long table, and was smoothing it down with her bony hands.

The Hockins trembled, not with cold, though it was mid-winter, but with terror. They dared not advance, and they felt powerless to retreat.

Then they saw Aunt Joanna go to the cupboard, open it, and return with the silver spoons; she placed all six on the sheet, and with a lean finger counted them.

She turned her face towards those who were watching her proceedings, but it was in shadow, and they could not distinguish the features nor note the expression with which she regarded them.

Presently she went back to the cupboard, and returned with the silver teapot. She stood at one end of the table, and now the reflection of the moon on the linen sheet was cast upon her face, and they saw that she was moving her lips—but no sound issued from them.

She thrust her hand into the teapot and drew forth the coins, one by one, and rolled them along the table. The Hockins saw the glint of the metal, and the shadow cast by each piece of money as it rolled. The first coin lodged at the further left-hand corner and the second rested near it; and so on, the pieces were rolled, and ranged themselves in order, ten in a row. Then the next ten were run across the white cloth in the same manner, and dropped over on their sides below the first row; thus also the third ten. And all the time the dead woman was mouthing, as though counting, but still inaudibly.

The couple stood motionless observing proceedings, till suddenly a cloud passed before the face of the moon, so dense as to eclipse the light.

Then in a paroxysm of terror both turned and fled up the stairs, bolted their bedroom door, and jumped into bed.

There was no sleep for them that night. In the gloom when the moon was concealed, in the glare when it shone forth, it was the same, they could hear the light rolling of the coins along the table, and the click as they fell over. Was the supply inexhaustible? It was not so, but apparently the dead woman did not weary of counting the coins. When all had been ranged, she could be heard moving to the further end of the table, and there recommencing the same proceeding of coin-rolling.

Not till near daybreak did this sound cease, and not till the maid, Sally, had begun to stir in the inner bedchamber did Hockin and his wife venture to rise. Neither would suffer the servant girl to descend till they had been down to see in what condition the kitchen was. They found that the table had been cleared, the coins were all back in the teapot, and that and the spoons were where they had themselves placed them. The sheet, moreover, was neatly folded, and replaced where it had been before.

The Hockins did not speak to one another of their experiences during the past night, so long as they were in the house, but when Jabez was in the field, Elizabeth went to him and said: “Husband, what about Aunt Joanna?”

“I don’t know—maybe it were a dream.”

“Curious us should ha’ dreamed alike.”

“I don’t know that; ‘twere the gin made us dream, and us both had gin, so us dreamed the same thing.”

“’Twere more like real truth than dream,” observed Elizabeth.

“We’ll take it as dream,” said Jabez. “Mebbe it won’t happen again.”

But precisely the same sounds were heard on the following night. The moon was obscured by thick clouds, and neither of the two had the courage to descend to the kitchen. But they could hear the patter of feet, and then the roll and click of the coins. Again sleep was impossible.

“Whatever shall we do?” asked Elizabeth Hockin next morning of her husband. “Us can’t go on like this wi’ the dead woman about our house nightly. There’s no tellin’ she might take it into her head to come upstairs and pull the sheets off us. As we took hers, she may think it fair to carry off ours.”

“I think,” said Jabez sorrowfully, “we’ll have to return ‘em.”

“But how?”

After some consultation the couple resolved on conveying all the deceased woman’s goods to the churchyard, by night, and placing them on her grave.

“I reckon,” said Hockin, “we’ll bide in the porch and watch what happens. If they be left there till mornin’, why we may carry ‘em back wi’ an easy conscience. We’ve spent some pounds over her buryin’.”

“What have it come to?”

“Three pounds five and fourpence, as I make it out.”

“Well,” said Elizabeth, “we must risk it.”

When night had fallen murk, the farmer and his wife crept from their house, carrying the linen sheets, the teapot, and the silver spoons. They did not start till late, for fear of encountering any villagers on the way, and not till after the maid, Sally, had gone to bed.

They fastened the farm door behind them. The night was dark and stormy, with scudding clouds, so dense as to make deep night, when they did not part and allow the moon to peer forth.

They walked timorously, and side by side, looking about them as they proceeded, and on reaching the churchyard gate they halted to pluck up courage before opening and venturing within. Jabez had furnished himself with a bottle of gin, to give courage to himself and his wife.

Together they heaped the articles that had belonged to Aunt Joanna upon the fresh grave, but as they did so the wind caught the linen and unfurled and flapped it, and they were forced to place stones upon it to hold it down.

Then, quaking with fear, they retreated to the church porch, and Jabez, uncorking the bottle, first took a long pull himself, and then presented it to his wife.

And now down came a tearing rain, driven by a blast from the Atlantic, howling among the gravestones, and screaming in the battlements of the tower and its bell-chamber windows. The night was so dark, and the rain fell so heavily, that they could see nothing for full half an hour. But then the clouds were rent asunder, and the moon glared white and ghastly over the churchyard.

Elizabeth caught her husband by the arm and pointed. There was, however, no need for her to indicate that on which his eyes were fixed already.

Both saw a lean hand come up out of the grave, and lay hold of one of the fine linen sheets and drag at it. They saw it drag the sheet by one corner, and then it went down underground, and the sheet followed, as though sucked down in a vortex; fold on fold it descended, till the entire sheet had disappeared.

“Her have taken it for her windin’ sheet,” whispered Elizabeth. “Whativer will her do wi’ the rest?”

“Have a drop o’ gin; this be terrible tryin’,” said Jabez in an undertone; and again the couple put their lips to the bottle, which came away considerably lighter after the draughts.

“Look!” gasped Elizabeth.

Again the lean hand with long fingers appeared above the soil, and this was seen groping about the grass till it laid hold of the teapot. Then it groped again, and gathered up the spoons, that flashed in the moonbeams. Next, up came the second hand, and a long arm that stretched along the grave till it reached the other sheets. At once, on being raised, these sheets were caught by the wind, and flapped and fluttered like half-hoisted sails. The hands retained them for a while till they bellied with the wind, and then let them go, and they were swept away by the blast across the churchyard, over the wall, and lodged in the carpenter’s yard that adjoined, among his timber.

“She have sent ‘em to the Hexts,” whispered Elizabeth.

Next the hands began to trifle with the teapot, and to shake out some of the coins.

In a minute some silver pieces were flung with so true an aim that they fell clinking down on the floor of the porch.

How many coins, how much money was cast, the couple were in no mood to estimate.

Then they saw the hands collect the pillow-cases, and proceed to roll up the teapot and silver spoons in them, and, that done, the white bundle was cast into the air, and caught by the wind and carried over the churchyard wall into the wheelwright’s yard.

At once a curtain of vapour rushed across the face of the moon, and again the graveyard was buried in darkness. Half an hour elapsed before the moon shone out again. Then the Hockins saw that nothing was stirring in the cemetery.

“I reckon us may go now,” said Jabez.

“Let us gather up what she chucked to us,” advised Elizabeth.

So the couple felt about the floor, and collected a number of coins. What they were they could not tell till they reached their home, and had lighted a candle.

“How much be it?” asked Elizabeth.

“Three pound five and fourpence, exact,” answered Jabez.