All that is really known of this eccentric character is found in a letter of J. B. to Richard Polwhele, dated September, 1814. His correspondent says:—

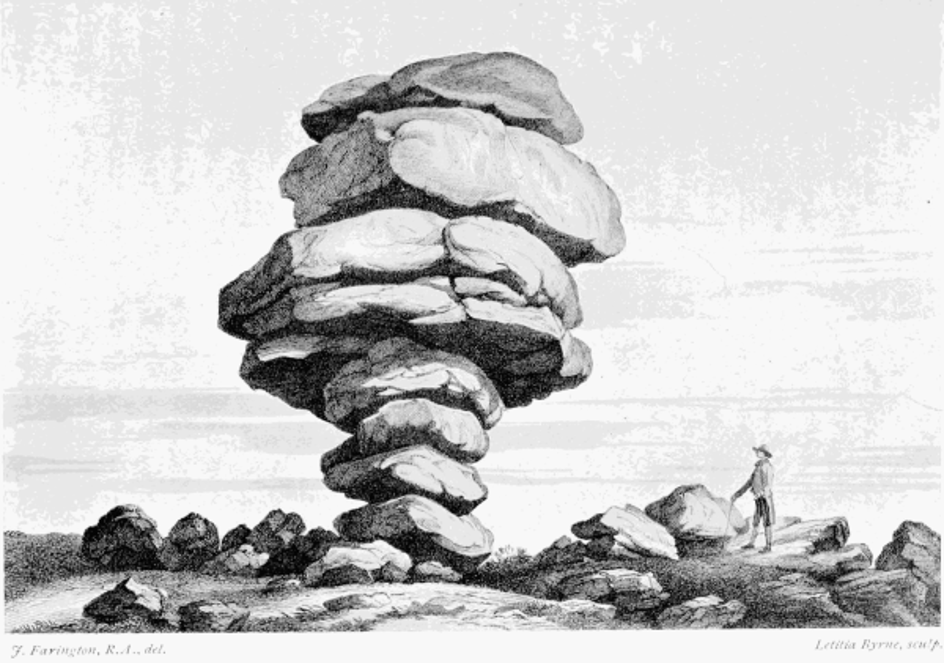

“Daniel Gumb was born in the parish of Linkinhorne, in Cornwall, about the commencement of the last century, and was bred a stone-cutter. In the early part of his life he was remarkable for his love of reading and a degree of reserve even exceeding what is observable in persons of studious habits. By close application Daniel acquired, even in his youth, a considerable stock of mathe-matical knowledge, and, in consequence, became celebrated throughout the ad-joining parishes. Called by his occupation to hew blocks of granite on the ne-ighbouring commons, and especially in the vicinity of that great natural curio-sity called the Cheesewring, he discovered near this spot an immense block, whose upper surface was an inclined plane. This, it struck him, might be made the roof of a habitation such as he desired; sufficiently secluded from the busy haunts of men to enable him to pursue his studies without interruption, whilst it was contiguous to the scene of his daily labour. Immediately Daniel went to work, and cautiously excavating the earth underneath, to nearly the extent of the stone above, he obtained a habitation which he thought sufficiently com-modious. The sides he lined with stone, cemented with lime, whilst a chimney was made by perforating the earth at one side of the roof. From the ele-vated spot on which stood this extraordinary dwelling could be seen Dartmoor and Exmoor on the east, Hartland on the north, the sea and the port of Plymo-uth on the south, and S. Austell and Bodmin Hills on the west, with all the in-termediate beautiful scenery. The top of the rock which roofed his house served Daniel for an observatory, where at every favourable opportunity he watched the motions of the heavenly bodies, and on the surface of which, with his chi-sel, he carved a variety of diagrams, illustrative of the most difficult problems of Euclid, etc. These he left behind him as evidences of the patience and inge-nuity with which he surmounted the obstacles that his station in life had placed in the way of his mental improvement.

“But the choice of his house and the mode in which he pursued his studies were not his only eccentricities. His house became his chapel also; and he was never known to descend from the craggy mountain on which it stood, to attend his parish church or any other place of worship.

“Death, which alike seizes on the philosopher and the fool, at length found out the retreat of Daniel Gumb, and lodged him in a house more narrow than that which he had dug for himself.”

Bond in his Topographical and Historical Sketches of the Boroughs of East and West Looe, 1873, describes the habitation of Daniel Gumb as seen by him in 1802:—

“When we reached Cheesewring—our guide first led us to the house of Daniel Gumb (a stone-cutter), cut by him out of a solid rock of granite. This artificial cavern may be about twelve feet deep and not quite so broad; the roof consists of one flat stone of many tons weight; supported by the natural rock on one side, and by pillars of small stones on the other. How Gumb formed this last support is not easily conceived. We entered with hesitation lest the covering should be our gravestone. On the right-hand side of the door is ‘D. Gumb,’ with a date engraved 1735 (or 3). On the upper part of the covering stone, channels are cut to carry off the rain, probably to cause it to fall into a bucket for his use; there is also engraved on it some geometrical device formed by Gumb, as the guide told us, who also said that Gumb was accounted a pretty sensible man. I have no hesitation in saying he must have been a pretty eccentric charac-ter to have fixed on this place for his habitation; but here he dwelt for several years with his wife and children, several of whom were born and died here. His calling was that of a stone-cutter, and he fixed himself on a spot where ma-terials could be met with to employ a thousand men for a thousand years.”

The Rev. Robert S. Hawker wrote an account of Daniel Gumb for All the Year Round in 1866, and this has been reprinted in Footsteps of Former Men in Cornwall.

He pretends that when he visited the Cheesewring in 183-, there still existed fragments of Daniel Gumb’s “thoughts and studies still treasured up in the exis-ting families of himself and his wife.” And he gives transcripts from these, and also from what must have been a diary. But Mr. Hawker embroidered facts with so much detail drawn from his own fancy, that his statements have to be taken with a very large pinch of salt.

It must be remembered, in his justification, that his stories of Cornish Charac-ters were intended as magazine articles to amuse, but without any purpose of having them regarded as strictly biographical and historical. They were brief historical romances, and were not intended to be taken seriously.

I will give but one quotation, and the reader can judge for himself therefrom whether it does not look like an extract “made in Morwenstow.” Mr. Hawker says:—

“On the fly-leaves of an old account book the following strange statement ap-pears: ‘June 23rd, 1764. To-day, at bright noon, I looked up and saw all at once a stranger standing on the turf, just above my block. He was dressed like an old picture I remember in the windows of S. Neot’s Church, in a long brown gar-ment, with a girdle; and his head was uncovered and grizzled with long hair. He spoke to me, and he said in a low, clear voice, “Daniel, that work is hard!” I wondered that he should know my name, and I answered, “Yes, sir; but I am used to it and don’t mind it, for the sake of the faces at home.” Then he said, sounding his words like a psalm, “Man goeth forth to his work and to his la-bour until the evening. When will it be night with Daniel Gumb?” I began to feel queer; it seemed to me that there was something awful about the unknown man. I even shook. Then he said again, “Fear nothing. The happiest man in all the earth is he that wins his daily bread by his daily sweat, if he will but fear God and do man no wrong.” I bent down my head like any one dumbfounded, and I greatly wondered who this strange appearance could be. He was not like a preacher, for he looked me full in the face; nor a bit like a parson, for he see-med very meek and kind. I began to think it was a spirit, only such ones always come by night, and here was I at noonday and at work. So I made up my mind to drop my hammer and step up and ask his name right out. But when I looked up he was gone, and that clear out of my sight, on the bare, wide moor, sud-denly.’”

Now, in the first place, no trace or tidings of these notes so treasured up by the family are to be found in the parish of Linkinhorne, to which Gumb and his wife belonged.

In the second place, Mr. Hawker makes Daniel remark that his mysterious visi-tant was not like a Dissenting preacher because he looked him straight in the face, and this is significantly like a remark Hawker often made with regard to these gentry.

Another of these pretended notes refers to the finding of a fossil fish embedded in granite. This alone suffices to wake suspicion that the extracts are not genu-ine. Fossils never have been found in granite, and never will be. But Hawker himself did not know this, as he was totally ignorant of the first principles of geology.