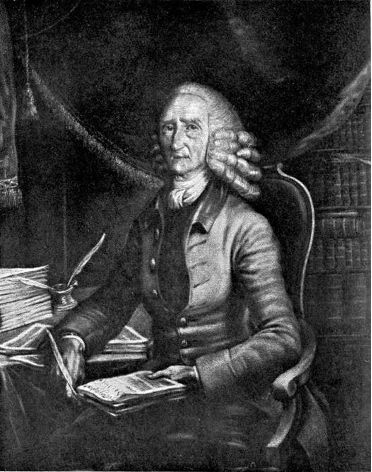

The simple and quiet life of a country gentleman who does not hunt, but spends his days in the library among books, or at his desk making calculations, presents little of interest to the general reader. But Davies Gilbert is not a man to be passed over in a collection of minor worthies of Cornwall.

Mr. Gilbert’s original name was Giddy, and he was the grandson of a Mr. John Giddy, of Truro, who had two sons, Edward and Thomas; the former took Holy Orders, and became curate of S. Erth, and never obtained any better preferment. Here he married Catherine, daughter of John Davis, of Tredrea, the representative of several ancient families, and inheriting what fragments were left of the property of William Noye, Attorney-General in the reign of Charles I.

At S. Erth was born, 6 March, 1767, Davies Giddy, the subject of this sketch. After having been

The whining schoolboy, with his satchel,And shining morning face, creeping like snailUnwillingly to school,

at Penzance, he passed to Oxford, and entered Pembroke College, his father going up to Oxford to reside with him. Dr. Johnson, who was also of Pembroke, once said, in allusion to the poetical characters brought up there, that it was a veritable nest of singing-birds. Davies Giddy was not a singer or a poet himself, but taught others to sing, for he collected and published the traditional Cornish carols with their melodies, now taken into every book of Christmas carols and sung at the feast of Noël from John o’ Groats House to the Land’s End, in America, India, and Australia. Probably this little gathering was one of the works Davies Giddy, or Gilbert, least valued of his many productions, but it has been the most enduring, and will be deathless so long as English voices carol.

Contemporary with Davies Giddy, but of older standing in the college, was that strange man Dr. Thomas Beddoes, lecturer on chemistry, whose head was turned by fanatical republicanism, and who was an enthusiastic admirer of the French Revolution, and prepared to condone the horrors of the Reign of Terror. This was too much for most of Beddoes’ friends, who fell away from him, but Davies Giddy, though in politics standing at the other pole, appreciated the great abilities of the doctor, shrugged his shoulders at his political opinions, and refrained from absolutely breaking off all intercourse with him, even when Beddoes was obliged to resign the professorship he held at the University.

Beddoes, on leaving Oxford, set up a pneumatic institution at Clifton, near Bristol, for the cure of consumption, by pumping air into the lungs of those afflicted with phthisis. This was a great discovery, which was to sweep this scourge out of England. The pneumatic bellows worked night and day, and the patients gasped, inhaled and spurted the air back through their nostrils, till the arms of the bellows-workers ached, but, alas for suffering mankind, the pneumatic process proved a dead failure.

Davies Giddy after leaving Oxford went to a surgeon, Bingham Borlase, at Penzance, to prepare for the medical profession, intending after a stay with Borlase to complete his education at the Medical School of Edinburgh. With Dr. Borlase was a lad, Humphry Davy, who had been articled to him in 1793, when little more than fourteen years old. He was a youth of active frame, and with a bright, intelligent face, with wavy brown hair, and eyes “tremulous with light.” Not only was Davy a keen fisherman, but he was enthusiastic as a chemist; but he had no particular desire to spend his life as a Sangrado in Penzance. Davies Giddy speedily recognized the flashes of genius in the lad, and recommended him to go to the pump-house of Dr. Beddoes as an assistant at a modest salary. As Beddoes experimented with various gases on his unfortunate patients there was at all events an element of novelty in the venture. Mr. Giddy abandoned his intention of entering the medical profession, and, having a sufficient income to support himself, he devoted his whole time to scientific work, and became well known as a geologist and botanist, and he associated with all the literary and scientific men of his native duchy.

The introduction of Watt’s improvement in the steam-engine into the Cornish mines and the disputes between that great mechanical inventor and Jonathan Hornblower, of Penryn, as to the economy and mode of applying the principle of working steam expansively, early attracted the attention of Davies Giddy, and Hornblower had frequent recourse to him, as a mathematician, to work out his calculations for him, and to advise as to his experiments, and approve or criticize his inventions. Trevithick also had recourse constantly for the same purpose to Mr. Giddy, and the latter was solicited by the county to take an active part in determining the advantages of Watt’s engines; and in conjunction with Captain W. Jenkin, of Treworgie, he made a survey of all the steam-engines then working in Cornwall.

One of the most laborious and practically useful works of Giddy was a treatise on the properties of the Catenary Curve. This fine example of mathematical investigation was published whilst Telford was preparing materials for the Menai Straits Bridge; and Telford was so convinced by Mr. Giddy’s tract, that he altered the construction of the bridge in accordance with what Giddy had laid down, causing the suspension chains, which had already been completed, to be again taken in hand and lengthened by about thirty-six feet.

In 1804 Giddy was elected into Parliament as representative of that rotten borough Helston, but at the next election, in 1806, he was returned for Bodmin, and continued its member till the Reform Bill abolished these nests of corruption. In Parliament he was rarely heard to speak, but his judgment was always valued there, and had great influence on questions of a practical nature.

In 1811, when the high price of gold produced an ominous effect on the currency of the realm, and when the public mind became greatly agitated by the depreciation of bank notes, Davies Giddy published A Plain Statement of the Bullion Question, with the object of allaying the public ferment. Against great opposition he carried an extra twelve feet in width to the design for rebuilding London Bridge.

In 1808 he married Mary Ann Gilbert, an heiress, of Eastbourne, in Sussex, whose family name he afterwards assumed, on account of the hereditary estates to which he became entitled through this marriage.

This lady was of a strong, determined character. On one occasion when riding she was thrown, and dislocated her shoulder. Laying hold of her hunting-crop with both hands, she threw herself back and so brought the joint back into its place.

Once she had a dispute with some farmers, who would not continue their farms without a great reduction of rent. “Very well,” said she; “then I will farm them myself.” And she did so, and made them pay. She was the first in England to introduce the allotment system on a farm of hers at Eastbourne, Sussex. The marriage was due to Mr. Giddy meeting her when she was staying with her mother on a visit to Mr. Fry at Penzance.

She was a handsome woman, with a determined face, and she suited her husband admirably, for she was interested in many of the subjects that he took up. She was an authoress, moreover—she wrote upon “Tanks,” “On an Improved Mode of Forming Water Tanks,” “On the Construction of Tanks,” in 1836, 1838, and 1840. Also “On the Self-supporting Reading, Writing, and Agricultural School at Willingdon, in Sussex,” 1842.

On the death of Sir Joseph Banks the unanimous voice of the Royal Society called Sir Humphry Davy to the chair, and at the same time Davies Gilbert—as he now was—was nominated Treasurer under the man whom he had first helped to start in his career. Ill-health having obliged Sir Humphry Davy to quit England in the early part of 1827, Mr. Gilbert occupied the chair as Vice-President, and when finally Sir Humphry retired in the same year he was chosen President.

At that time a President was elected for life, but Davies Gilbert considered this to be unadvisable, and urged that the election should be for a term only; and his recommendation was accepted after a few years, when the presidency was required for the Duke of Sussex; thereupon it was hinted to him that he should act upon his expressed opinion and leave the chair for His Royal Highness. This he did without reluctance.

On his wife’s estate in Sussex he introduced the Cornish stiles, of gridiron fashion—strips of stone laid down with an interval between each—and this prevents horses, donkeys, and cattle from adventuring to cross them. But the Sussex people on the Eastbourne estate revolted, and declared that they would not break their legs to please any Cornish Giddy or Sussex Gilbert, and he was constrained to remove them all.

He was a man of a versatile mind. He published, with a translation by J. Keigwin and W. Jordan, the early Cornish mystery plays of Mount Calvary and the Creation of the World.

He also undertook a Parochial History of Cornwall, giving first Hals’ account from his MS., now in the British Museum, with additions from Tonkin, and a geological account of each parish by Dr. Boase, of no great value, and his own additions. This was published in five volumes in 1838.

He wrote also on steam-engines, on the employment of sea salt as a manure, on the improvement of wheels and springs for carriages, on the Eikon Basilike. He translated the Liturgy into Greek. Chambers in his Journal, Vol. II, 1844, has an account of the improvements effected on his wife’s estate at Eastbourne.

When Lieutenant Goldsmith upset the Logan Rock he got the use of timber and ropes granted for the work of replacing the stone, and had the loan of the same also to replace the coverstone of Lanyon Quoit.

Lord Sidmouth offered him the position of Under-Secretary of State, but he declined the offer.

About a year before his death Davies Gilbert entered in his notebook: “Slept in a house for the first time on my own property.” This was a house in East Looe bequeathed to him by Thomas Bond, who had written the History of Looe, and who died unmarried and without near relatives.

Davies Gilbert died at Eastbourne on Christmas Eve, 1839, as the carollers, for whom he had done so much, were going round in the dark under the stars singing—

Noël, Noël, the angel did say,Unto these poor shepherds in the fields as they lay.