The Tregion or Tregian family was one of great antiquity and large landed estates in Cornwall. Indeed, in the reign of Elizabeth it was estimated that the landed property brought in £3000 per annum, which represents a very much larger sum now. Their principal seat was Wolvedon, or Golden, in the parish of Probus, and this, when Leland wrote in the reign of Henry VIII, was in process of being built with great magnificence. But bad days were in store for some of the Cornish families that would not accept the changes in religion.

Carew, in his Survey of Cornwall, 1602, speaking of Tregarrick, then the residence of Mr. Buller, the sheriff, says: “It was sometime the Wideslade’s inheritance, until the father’s rebellion forfeited it,” and the “son then led a walking life with his harp to gentlemen’s houses, where-through, and by his other active qualities, he was entitled Sir Tristram; neither wanted he (as some say) a belle Isounde, the more aptly to resemble his pattern.”

The rebellion referred to was the rising in the West against the religious innovations, that was put down so ruthlessly.

During the first years of Elizabeth there had been no persecution of the Papists. Such as would not conform to the Church of England as reformed were allowed to have priests to say Mass in their own private chapels. But after Pius V, on April 27th, 1570, had issued a Bull of excommunication against the Queen, depriving her of her title to the crown, and absolving her subjects from their oaths of allegiance; and when it became evident that insurrections were being provoked by secret agents from Rome in all directions, Elizabeth’s patience was at an end, and stringent laws were passed against those who should enter England as missionary priests armed with this Bull and with dispensations, as also against all such as should harbour them.

On S. Bartholomew’s Day, August 24th, 1572, had taken place a massacre of the Huguenots in Paris and throughout France, and this had been cordially approved by Pope Gregory XIII, who had had a medal struck to commemorate what he considered a meritorious deed. There could exist no doubt that the Papal emissaries in England were encouraged to assassinate the Queen, though evidence to that effect was not obtained till later.

On June 8th, 1577, Sir Richard Grenville of Stow, sheriff of Cornwall, accompanied by some of his justices of peace, arrived at Wolvedon to search the house for Cuthbert Mayne, a priest who had arrived in England, and who, it was supposed, was harboured by Mr. Francis Tregian.

A hasty and superficial investigation was made, and no seminary priest could be found. Then Mr. Tregian invited the whole party in to dine with him, and when they had been well regaled, and were somewhat flushed with wine, Tregian foolishly joked with the sheriff for hunting and finding nothing. Sir Richard started up and vowed he would make a further inquest, and that more thorough, and, finally, concealed in a hole under a turret, Cuthbert Mayne was discovered, drawn forth, and with him Tregian, for having harboured him, was sent to Launceston gaol, there to await trial.

“In the gaol aforesaid, he was laid in a most loathsome and lousy dungeon, laden with irons, deprived of the use of writing, and bereaved of the comfort of reading, neither permitted that any man might talk with him touching any matter whatsoever, but by special licence and in presence of the keeper.”

The assizes were held at Launceston on the 16th September, 1577, when indictments were made against Cuthbert Mayne; Francis Tregian, Esq.; Richard Tremaine, gentleman, of Tregonnan; John Kempe, gentleman, of Rosteague; Richard Hore, gentleman, of Trenoweth, and others. Cuthbert Mayne for high treason: the others fell under the Statute of Præmunire, and later and more specific acts.

The Statute of Præmunire was but one of several that had been enacted from the time of Edward III, against papal interference with the affairs of England. The Statute of Præmunire was passed in 1393. “Whoever procures at Rome or elsewhere, any translations, processes, excommunications, bulls, instruments, or other things which touch the King, against him, his crown, and realms, and all persons aiding and assisting therein, shall be put out of the King’s protection, their lands and goods forfeited to the King’s use, and they shall be attached by their bodies to answer to the King and his Counsel: or process of præmunire facias shall be made out against them, as in any other case of prisoners.”

The Bull that had been found in the possession of Cuthbert Mayne was one from Pope Gregory XIII granting plenary absolution from all their sins to English Papists, as they were unable to attend the Pope’s jubilee at Rome, on condition that they should recite the Rosary fifteen times.

The Bull might very well have been treated with the contempt it merited, but the fact of the possession of such a document by Cuthbert Mayne was enough to procure his condemnation, as it was against the laws of England, and had been so for over one hundred and eighty years.

The other gentlemen were liable either as having received Cuthbert Mayne into their houses, or as having heard him say Mass, and as absenting themselves from their parish church.

Here came in the sharpened provisions enacted under Henry VIII and Elizabeth.

As Judge Marwood said at the trial: “We have not to do with your papistical use in absolving of sins. You may keep it to yourselves, and although the date of the Bull was expired and out of force, as you have alleged, so was it always out of force with us, for we never did, or never do account any such thing to be of force or worth a straw, and yet the same is by law of this realm treason, and therefore thou hast deserved to die.”

The main indictment ran as follows:—

“Thou Cuthbert Maine art accused for that thou, the 1st October, in the eighteenth year of our Sovereign lady the Queen that now is, did traitorously obtain from the See of Rome a certain instrument printed, containing a pretended matter of absolution of divers subjects of the realm. The tenour of the which instrument doth follow in these words: Gregorius Episcopus, servus servorum Dei, etc., contrary to the form of a certain statute in the thirteenth year of our Sovereign lady the Queen, lately made and published, and contrary to her peace, crown, and dignity. And that you,” meaning the rest, “after the said instrument obtained as aforesaid, and knowing the said Cuthbert Maine to have obtained the same from the Apostolic See, the 30th day of April, in the nineteenth of our said Sovereign the Queen’s reign, at Golden aforesaid, did aid, maintain, and comfort the said Cuthbert Maine, of purpose and intent to extol and set forth the usurped power and authority of a foreign Prelate, that is to say, the Bishop of Rome, teaching and concerning the execution of the premises, contrary to the said statute and published as aforesaid, and contrary to the place of our Sovereign lady the Queen, her crown and dignity.”

There were other indictments, as that Cuthbert Mayne and these laymen had refused to attend service in the parish church, and that the priest had brought over a number of “vain things,” such as an Agnus Dei in silver or stone, which had been blessed by the Pope and had been accepted by the laymen.

They all pleaded “Not guilty,” but the evidence against them sufficed for the jury to find that they were guilty, whereupon Cuthbert Mayne was condemned to death, and the rest to forfeit all their lands and property and to be imprisoned.

“Whereupon there was a warrant sent unto the Sheriff of Cornwall for the execution of Cuthbert Maine. The day assigned for the same purpose was dedicated unto S. Andrew; but on the eve before, all the Justices of that County, with many preachers of the pretended reformed religion, being gathered together at Launceston, Cuthbert Maine was brought before them, his legs being not only laden with mighty irons, but his hands also fast fettered together (in which miserable case he had also remained many days before), when he maintained disputation with them concerning the controversy in religion all this day in question, from eight of the clock in the morning until it was almost dark night, continually standing, no doubt in great pain in that pitiful plight, on his feet.”

How that could be a great crime to distribute some trumpery toys of crystal, and silver medals marked with the Agnus Dei, one fails to see, but it is possible that they may have been regarded as badges, pledging those who received them to combine in a rebellion against the State, and perhaps also to unite in an assassination plot. That there was such a plot appeared afterwards from the confession of Father Tyrrell. At this time it was suspected, but not proved. That harsh and cruel treatment was dealt out to these men, we cannot doubt, but, as Mr. Froude remarks, “were a Brahmin to be found in the quarters of a Sepoy regiment scattering incendiary addresses, he would be hanged also.”

There were in all seven indictments.

At first Francis Tregian had not been committed to gaol, but he was so shortly after, was brought to trial, and was sentenced to the spoiling of his goods and to a lifelong imprisonment.

Barbarous as these persecutions and sentences seem to us to-day, there was some justification for the Queen and Council at the time, surrounded as they were with dangers.

The Papal Bull of excommunication had encouraged the supporters of Mary, Queen of Scots, and plots were made on her behalf which were a constant source of alarm to Elizabeth. One of these plots was managed by an Italian named Ridolfi; the Duke of Norfolk had a share in it, and was executed in consequence in 1572. The great fear was lest France or Spain should take advantage of the situation to invade England, while Mary’s friends raised insurrections at home. Mary’s friends were active in all parts. Numbers of young Popish priests, trained to hostility towards Elizabeth, were pouring into the country, and conspiracies against her life were numerous, explaining, though in no degree justifying the stringent laws against seminary priests and recusants.

To return to Cuthbert Mayne.

“Wherefore, according to the judgment he had received, the next day he was uneasily laid on a hurdle, and so drawn, receiving some knocks on his face and his fingers with a girdle, unto the market-place of the said town, where of purpose there was a very high gibbet erected, and all things else, both fire and knives, set to the show and ready prepared.

“At which place of execution, when he came, he was first forced to mount the ladder backward, and after permitted to use very few words. Notwithstanding he briefly opened the cause of his condemnation, and protested, that his master (Mr. Tregian) was never privy with his having of these things whereupon he was condemned—the Jubilee and the Agnus Dei; then one of the justices, interrupting his talk, commanded the hangman to put the rope about his neck, and then, quoth he, let him preach afterward. Which done, another commanded the ladder to be overturned, so as he had not the leisure to recite In manus tuas Domine to the end. With speed he was cut down, and with the fall had almost ended his life, for the gibbet being very high, and he being yet in the swing when the rope was cut, he fell in such sort, as his head encountered the scaffold which was there prepared of purpose to divide the quarters, as the one side of his face was sorely bruised, and one of his eyes far driven out of his head.

“After he was cut down, the hangman first spoiled him of his clothes, and then in butcherly manner, opening his belly, he rent up his bowels, and after tore out his heart, which he held up aloft in his hand, showing it unto the people. Lastly, his head was cut off, and his body divided into four quarters, which afterwards were dispersed and set up on the Castle of Launceston; one quarter sent unto Bodmin; another to Barnstaple; the third to Tregony, not a mile distant from Mr. Tregian’s house; the fourth to Wadebridge.”

Not only was Francis Tregian adjudged to forfeit his goods, but he was also prosecuted by a goldsmith, who claimed a debt of £70.

Accordingly he was sent up to London to the King’s Bench prison, “strongly guarded by a ruffianly sort of bloody blue-coats, with bows, bills, and guns”; and the arms of Tregian were pinioned behind his back with cords. With him were associated the other Papists; and they met with insult and harsh treatment all the way to London. There he was again tried and cast into prison.

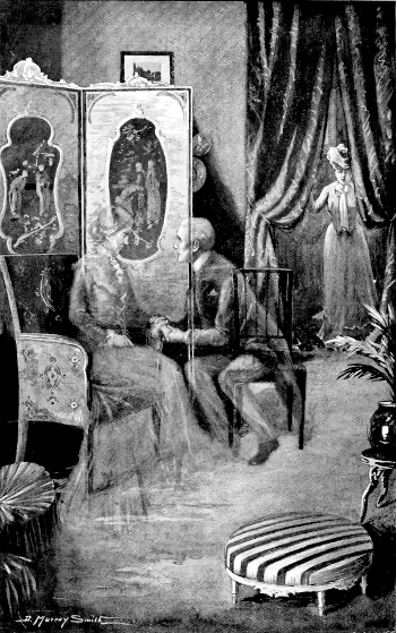

We are gravely informed that before these calamities befell Francis Tregian, a premonition of coming woes had been given to his wife.

“Mr. Tregian, her husband, not many days after they were first married, enforced for ten months to follow the Lords of the Council, his wife always in the mean season lying with a very virtuous maid, a sister of her husband’s, it chanced that one night looking for fleas, as the manner of women is, she espied in her smock sundry spots, the which she perceived to carry the shape of sundry crosses. Whereat she, much marvelling, besought her sister to behold the same; whereupon, when both had long looked and wondered, at length endeavouring to number them, they found contained in the same smock no less than one hundred and twenty-five crosses, and after, upon more curious search, they likewise found sundry other, both on her pillow and in her sheets.”

This omen of coming evil was now verified, but not by flea-bites. Francis Tregian remained in prison cruelly treated, and when he attempted to make his escape, manacled and fettered in a loathsome dungeon. From his cell he wrote in verse to his wife, but did not display much brilliancy of poetic art.

My wont is not to write in verse,You know, good wife, I wis.Wherefore you well may bear with me,Though now I write amiss;For lack of ink the candle coal,For pen a pin I use,The which also I may allegeIn part of my excuse.For said it is of many menAnd such as are no fools,A workman is but little worthIf he do want his tools;Though tools I have wherewith in sortMy mind I may disclose,They are, in truth, more fit to paintA nettle than a rose.

And so on, never rising to a higher level.

But his wife was allowed to visit him, and indeed reside with him in prison. “And although through the rigour of authority they have been often separated, sometimes two months, sometimes seven, sometimes more, she hath borne him, notwithstanding, eleven children since he was first imprisoned. Some are dead, but the most part are alive.”

Francis Tregian was first committed to prison in the twenty-eighth year of his age, and in the year 1595, when he had been about sixteen years in prison, some notes were drawn up concerning him, from which some quotations may be made.

In all the sixteen years’ space he had never been permitted to enjoy the benefit of the open air otherwise than when being removed from one prison to another. He was first imprisoned at Launceston, then was removed to Windsor Castle; thence removed to the Marshalsea, and then again carried back to Launceston Castle. Then he was conveyed to the King’s Bench prison, and lastly to the Fleet.

For seven or eight years together he enjoyed good health; “but in the end, through cares, studies, filthy diet, most stinking air, and want of exercise, he became very sickly, and so continued by the space of six or seven years; notwithstanding at this present the state of his body is much mended, and is like to recover his perfect health.”

His mother was the eldest sister of Sir John Arundell, Knight, of Lanherne. His great-grandmother was one of the daughters of Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorchester, half-brother to Queen Elizabeth, the wife of King Henry VII, and daughter of Edward IV. He married the eldest sister of Lord Stourton. His wife’s mother was eldest sister of the Earl of Derby. Francis Tregian remained in prison eighteen years, and was finally released by order of Queen Elizabeth in or about 1597, after which he lived in London on the bounty of his friends.

His son, Francis, managed to repossess himself, by the assistance of some of his friends and relatives, by purchase of some portion of the ancestral property, but in January, 1608, owing to the hostility provoked by the Gunpowder Plot against the Papists, the family was again plundered of the estates, and when the Heralds’ Visitation of Cornwall was taken in 1620, the family had disappeared from the list of the landed and heraldic gentry.

Francis Tregian, the elder, at last retired to Lisbon, where he died on the 25th September, 1608. He was allowed by the King of Portugal sixty crowns a month. On his tombstone it was stated, falsely, that he had endured twenty-eight years of imprisonment in England. As a specimen of the malignant lies that were spread abroad relative to Queen Elizabeth, is this—given in a life of Francis Tregian by Francis Plunket, son of one of his daughters:—

“Aulam Elizabethæ adit … Regina per pedissequam illum invitat ad cubiculum, intempesta nocte; recusantem adit, lectoque assistens ad impudica provocat; rennentem increpat. Castitati suæ cusam gerens ex Aula se proripuit, insalutata Regina; quæ idcirco furit, et in carcerem detrudi jubet.”

Such words fill one with disgust and indignation against the pack from Rheims and Rome, who, unable to reach the Queen with their daggers, bespattered her with foul words.

The Life of Francis Tregian was published in Portuguese, at Lisbon, by Francis Plunket, in 1655. The narrative of his imprisonment, written in 1593, is published in extenso by J. Morris, The Troubles of our Catholic Forefathers, 1st series, London, 1872, from the original MS. in S. Mary’s College, Oscott.

A summary is in C. S. Gilbert’s Historical Survey of Cornwall, 1817.