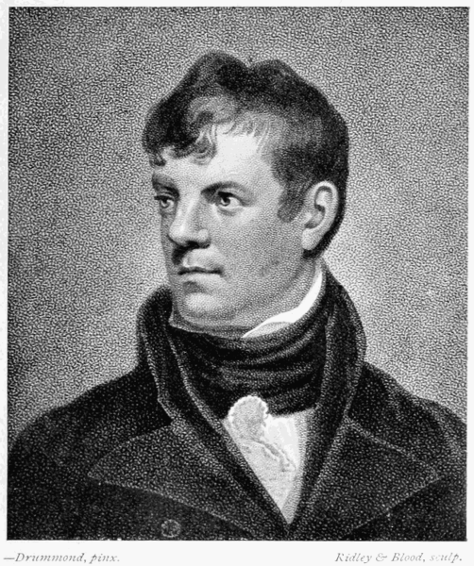

The record of the adventures of this man is fully as interesting as the fictitious story of Robinson Crusoe and well deserves republication. It was first published in Exeter in 1837. Two editions of a thousand copies each were exhausted, and a third was published in 1839, and a fourth in 1841.

George Medyett Goodridge was born at Paignton on 22 May, 1796. At the age of thirteen he hired himself as cabin-boy on board the Lord Cochrane, an armed brig, stationed off Torquay to protect the fishing craft from French cruisers. From that time till 1820 he was continually at sea; in that year, on 1 May, he joined the Princess of Wales, a cutter, burthen seventy-five tons, bound for the South Seas after oil, fins, seal-skins, and ambergris. The arrangement was that out of every ninety skins procured, each mariner should have one; the boys proportionately less; and the officers proportionately more. Captain Veale was commander, Mazora, an Italian, mate; there were in addition three boys and ten mariners.

In descending the Thames from Limehouse, a Captain Cox went on board and made a present to the crew of a Bible. “We thought little of the gift at the time,” says Goodridge, “but the sequel will show that this proved to be the most valuable of all our stores.” In passing down the Channel, the vessel was wind-bound for several days, and Goodridge was able to visit his friends at Paignton, and bid them farewell. “On the 21st, being Whit Sunday, the weather proved fine, with a breeze from the northward, we again weighed anchor and proceeded on our voyage.”

On 2 November the vessel reached the Crozets, a group of five islands in the South Pacific Ocean.

“As there is no harbour for shelter, the plan pursued is, for one party to go on shore, provided with necessary provisions for several days, while the remainder of the crew remain to take care of the vessel, and to salt in the skins that have been procured. The prevailing winds are from the westward, and we used to lie with our vessel under the shelter of the island, and whenever the wind shifted to the eastward, which it sometimes did very suddenly, we had to weigh our anchor, or slip the cable, and stand out to sea. The easterly wind scarcely ever lasted more than two days, when it would chop round to the northward, with rain, and then come round to W.N.W. We should then return to our shelter, take on board the skins collected, and again furnish the sealing party with provisions. The most boisterous season of the year in these latitudes commences in August, during which month the most tremendous gales are experienced, with much snow, rain and hail.

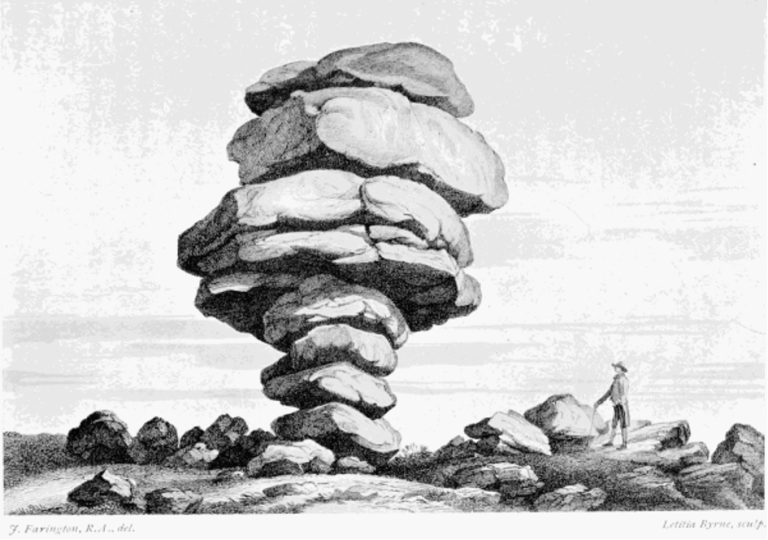

“The hardships and privations experienced in procuring seal-skins on these islands may be faintly conjectured, when I state the plan pursued by the parties on shore. The land affords no shelter whatever, there being neither tree nor shrub, and the weather is at most times extremely wet, and snow frequently on the ground, indeed, there is scarcely more than a month’s fine weather during the year. Their boat, therefore, hauled on shore, serves them for their dwelling house by day, and their lodging house by night. Their ] provisions consist of salt pork, bread, coffee, and molasses; on this scanty fare, with the shelter of their boat only turned upside down, and tussicked up, they sometimes remain a fortnight at a time, each day undergoing excessive labour in searching for and killing seals, and very often without meeting with an adequate reward after all their privations. Added to this, when a gale renders it necessary for their vessel to drive to sea, each hour she is absent, the mind is harassed with fears for her safety, and of the consequences that would result to themselves if thus left on such a desolate spot, surrounded by a vast ocean, and where years might pass without a vessel ever coming near them.”

The largest of the islands is about twenty-five miles in circumference, and lies about thirty miles distant from one of the small ones, and about twelve miles from the other. The other two islands lie about twenty miles to the eastward of the three first.

On 5 February a sealing party, consisting of eight, was landed on the easternmost island, and the remaining seven proceeded with the vessel to the other island. Those in the vessel consisted of the master, Captain Veale, of Dartmouth, and his brother, Jarvis Veale, Goodridge, Parnel, Hooper, Baker, and a Hanoverian named Newbee. The vessel visited the sealing party every seven days, took on board the skins collected, and supplied them with a fresh stock of provisions; that done it returned to the other island, where the crew also employed themselves in collecting seal-skins.

The last visit made to the easternmost island was on 10 March, and the next visit would have been on the 18th had not a gale come on, on the 17th, that compelled the captain to stand off, and gain the offing.

“We accordingly slipped our cable and stood to sea, but before we had proceeded any distance, it came on a dead calm, so that we entirely lost command of the vessel, the swell of the sea continuing at the same time so heavy that our boat was useless; for any attempt at towing her in such a swell, and against a strong current which was making directly on the land, was utterly vain. The island presented to our view a perpendicular cliff, with numerous rocks protruding into the sea, and against them we were driven, victims to the unspent power of a raging sea, lashed into fury by winds which now seemed hushed into breathless silence, the more calmly to witness the effects of the agitation raised by them in the bosom of the ocean. We attempted to sound for bottom, in hope that we might have recourse to our anchor; but the hope was vain, as our longest lengths of line were found inadequate to reach it. It was now ten at night, and from this time till midnight we were in momentary expectation of striking. The suspense was truly awful, indeed, the horrors we experienced were more dreadful than I had ever felt or witnessed in the most violent storms; for on such occasions the persevering spirits of Englishmen will struggle with the elements to the last blast and the last wave; but here there was nothing to combat; we were driven on by an invisible power—all was calm above us—around us the surface of the sea, although raised into a mountainous swell, was smooth; but the distant sound of its continued crash on the breakers to which we were drawn by irresistible force, broke on our ears as our death knell. At last the awful moment arrived, and about 12 o’clock at night, our vessel struck with great violence. Although previous to her striking all hands appeared paralysed, now arrived the period of action. The boat was fortunately got out without accident, and all hands got into her with such articles as we could immediately put our hands on, among which were a kettle, a frying-pan, our knives and steels, and a fire-bag (this article is a tinder-box supplied with cotton matches, and carefully secured from damp in a tarpaulin bag), but without any provisions or clothes except what we stood upright in.

“The night was dark and rainy, and the vessel was pitching bowsprit under; we were surrounded by rocks, and the nearest shore was a perpendicular cliff of great height. We however tugged at the oars, but made little progress, the kelp being extremely thick, long and strong, and the current running direct to the shore. After four hours incessant labour, we succeeded in effecting a landing, on a more accessible part of the island, but our boat was swamped, and it was with great difficulty we succeeded at length in dragging her ashore; which however we accomplished, and by turning her bottom upwards, and propping up one side as before described, we crept under and obtained some little shelter from the rain, being all miserably cold, wet and hungry.

“We remained huddled together till daylight appeared, and our craving appetites then told us it was time to seek for sustenance; we therefore sallied forth in search of a sea-elephant; and although they were rather scarce at this period of the year, it was not long before we found one; nor was it long before we dispatched it. With its blubber we soon kindled a fire, and the heart, tongue, and such other parts as were edible, with the assistance of our kettle and frying-pan, were soon in a forward state of cookery. We also made a fire of some blubber under our boat, and by it we dried our clothes, and made ourselves more comfortable.

“When we were in some measure refreshed, and had recruited our strength with the food we had procured, a party of us set out over the hills, in the direction of the spot where the vessel was wrecked, in order to ascertain her fate, and to see if there was a possibility of saving anything out of her. They returned about the middle of the day, and reported that she was lying on the rocks, on her beam ends, with a large hole in her lower planks, and the sea breaking over her; so that it was impossible she should hold together much longer; it was evident, therefore, that all hope of saving her was at an end, and our endeavours could now only be exerted for the purpose of saving any portion of the wreck that might prove serviceable to us in our desolate situation.

“On the following morning we succeeded in launching our boat, and we then proceeded towards the wreck. In our progress we discovered a cove much nearer the vessel than where we landed, and we resolved to make this our immediate station.

“We next visited the wreck, and succeeded in saving the captain’s chest, the mate’s chest, and also some planks. The last thing we saved, and which we found floating on the water, was the identical Bible put on board by Captain Cox. What made this circumstance more remarkable was, that although we had a variety of other books on board, such as our navigation books, journals, log-books, etc., this was the only article of the kind that we found, nor did we discover the smallest shred of paper of any kind, except this Bible.

“On the next day the wind blew very strong, and we saw that nothing remained of our vessel but the mast, which had become entangled by the rigging among the rocks and sea weed, and this was the last thing we were enabled to secure.

“The weather continued so wet and boisterous for three weeks from this time, that it was as much as we could well do to procure necessary food for our sustenance, and we therefore contented ourselves with the shelter our boat, tussicked up, afforded us during that period; the weather at last proving less inclement, we set about collecting all the materials we had saved, and then commenced erecting for ourselves a more commodious dwelling-place. The sides we formed of stones and the wood saved from the wreck, for there was not shrub or tree growing on the whole island. The top we covered with sea-elephants’ skins, and at the end of a few weeks we were comparatively well lodged. We made our beds of the long grass, called tussick, with which the island abounded; and the skins of the seals we chanced to kill served us for sheets, blankets, and counterpanes. Wanting glass we were obliged to do without windows; the same opening, therefore, that served us for entrance, served us also for the admission of light and air; and when the weather obliged us to shut out the cold, we were obliged to shut out the light of day also.

“While constructing our hut, we found on the island traces of some Americans who had visited these islands sixteen years before, and who had built a hut. The sea-elephants, however, had trodden almost everything into the ground; and as we had no tools wherewith to dig, we could not search for anything they might have left. Providence, however, at length threw the means in our way of effecting our wishes; for one of our company, while searching for eggs at a considerable distance from our building, found a pick-axe, and brought it home in high glee. To men situated as we were, it was not to be wondered at that we should deem this almost a miracle. Suffice it to say, we all returned our hearty thanks for the favour, and set to work digging up the place where traces of the hut remained. Our labour proved not to be in vain, for we got up a quantity of timber; also part of a pitch-pot, which would hold about a gallon. This proved highly valuable to us, for, by the help of a piece of hoop-iron, we manufactured it into a frying-pan, our other being worn so thin by constant use, that it was scarcely fit to cook in. Digging further we found a broad axe, a sharpening-stone, a piece of a shovel, and an auger; also a number of iron hoops. These things were of essential service to us. We did not save any of our lances from the ship, and we had often considerable labour to kill the large male sea-elephants; but we now took the handle of our old frying-pan, and with the help of the sharpening-stone, gave it a good point; we then fixed it in a handle, and with this weapon we dispatched these animals with ease.

“The dog-seals are named by South-seamen Wigs, and the female seals are called Clap-matches. The Wigs are larger than the largest Newfoundland dog, and their bark is somewhat similar. When attacked they would attempt to bite; and it required some dexterity to avoid their teeth, the wounds from which were difficult to heal. The flesh we found very rank. The young ones are usually denominated Pompeys, and are excellent for food.

“The supply of seals we found very scanty; our principal dependence, therefore, was on the sea-elephants, which, from their great tameness, became an easy prey. They served us for meat, washing, lodging, firing, grates, washing-tubs, and tobacco pipes. The parts we made use of for food, were the heart, tongue, sweetbread, and the tender parts of the skin; the snotters (a sort of fleshy skin which hangs over the nose) and the flappers. These, after boiling a considerable time, formed a jelly, and made, with the addition of some eggs, adding a pigeon or two, or a sea-hen, very good soup. The blood served to wash with, as it quickly removed either dirt or grease. When we had articles that needed washing, and had killed an elephant, we used to turn the carcase on its back, and the intestines being taken out, a quantity of blood would flow into the cavity. In this we cleansed the articles, and then rinsing them in the stream, they were washed as well as if we had been provided with soap.

“The skins served us for roofing, and of them we also formed our shoes or moccasins, and these we used to sew together with thongs formed from the sinews. Their teeth we formed into the bowls of pipes, and to this attached the leg bone of some water-fowl, and together it formed a good apparatus. Having no tobacco, we used the dried grass that grew on the island.

“Of sea-elephants’ blubber we made our fires, and their bones laid across on some stones formed grates to lay the blubber on. Of a piece of blubber also, with a piece of rope-yarn stuck in it, we formed our lamps, and it produced a very good light. The largest elephants are about 25 ft. long and 18 ft. round, and their blubber was frequently 7 in. thick and would yield a tun of oil. The brain of the animal, which was almost as sweet as sugar, was frequently eaten by us raw. The only kind of vegetable on the island, besides grass, was a plant resembling a cabbage, but we found it so bitter that we could make no use of it.

“Mr. Veale had fortunately saved his watch uninjured, so we were able to divide our time pretty regularly. We usually rose about 8 in the morning, and took breakfast at 9 o’clock; after breakfast some of the party would go catering for the day’s provisions, while the others remained at home to fulfil the domestic offices. We dined generally about 1 o’clock, and took tea about 5. For some months this latter meal, as far as the beverage went, consisted of boiled water only, but we afterwards manufactured what we named Mocoa as a substitute for tea, and this consisted of raw eggs beat up in hot water. We supped about 7 or 8 o’clock, and generally retired to rest about 10.

“I have before said that the most valuable thing we preserved from the wreck was our Bible, and here I must state that some portion of each day was set apart for reading it; and by nothing perhaps could I better exemplify its benefits than by stating that to its influence we were indebted for an almost unparalleled unanimity during the whole time we were on the island. Peace reigned among us, for the precepts of Him who was the harbinger of Peace and Goodwill towards men were daily inculcated and daily practised. The Bible when bestowed was thrown by unheeded: it traversed wide oceans, it was scattered with the wreck of our frail bark, and was indeed and in truth found upon the waters after many days, and not only was the mere book found, but its value was also discovered, and its blessings, so long neglected, were now made apparent to us. Cast away on a desert island, in the midst of an immense ocean, without a hope of deliverance, lost to all human sympathy, mourned as dead by our kindred, in this invaluable book we found the herald of hope, the balm and consolation, the dispenser of peace.

“Another striking fact may here be stated. One of our crew was a professed Atheist: he was, however, extremely ignorant, not being able even to read. This man had frequently derided our religious exercises, but having no one to second him, it did not disturb the harmony that reigned among us.

“This man’s conversion was occasioned by an interposition which he deemed supernatural. The story he gave of himself was as follows: He had been out seeking for provender alone, and evening closed on him before he could reach our dwelling. The darkness perplexed him, and the ground which he had to cross being very uneven and interspersed with many rocks and declivities, fear rather increased than decreased his power of perception, and he became unable to proceed.”

It may here be added that one of the great dangers of the island were the bog-holes, Goodridge supposes worked in the soil by the bull-elephants; these are eight or nine feet deep and become full of mire: any one stepping in would suddenly be engulfed.

“Here he first felt his own weakness; he hallooed loudly for help, but he was far out of hearing of our abode. Bereft of all human aid, and every moment adding to his fear, he at length called on the name of his Maker and Saviour, and implored that assistance from Heaven which he had before so often scorned. He prayed now most fervently for deliverance, and suddenly, as he conceived, a light appeared around him, by which he was enabled to discover his path and reach our hut in safety. So fully satisfied was he himself that it was a miraculous interposition of Providence that from that period he became quite another man.

“Great numbers of birds visit these islands. There are three species of Penguins beside the King Penguin, and these are named by South Sea men, Macaroonys, Johnnys, and Rock Hoppers. The Macaroonys congregate in their rookeries in great numbers, frequently three or four thousand; they ascend very high up the hills, and form their nests roughly among the rocks. They are larger than a duck, and lay three eggs, two about the size of duck’s eggs, on which they sit; the other is smaller, and is cast out of the nest, and we used to term it the pigeon’s egg, for another kind of bird which frequent these islands, almost in every respect resembling a pigeon, make their principal food of eggs, and would rob the nests to procure them unless they found those cast-out eggs, which most commonly satisfied them till the others by incubation were unfit for food. A similar practice we observed with the Rock Hoppers, but the Johnnys, like the King Penguins, lay only one egg each, unless deprived of them.

“The Johnnys build their nests superior to either of the others among the long grass. These birds lay in winter as well as in summer, and by robbing their nests we kept them laying nearly all the year round. We observed that when we robbed those which formed their nests on the plain, that they rebuilt their nests higher up. When we took the eggs of these birds, they would look at us most piteously, making a low, moaning noise, as if in great distress at the deprivation, but would exhibit no kind of resistance. The King Penguins, however, would strike at us with their flippers, and their blows were frequently severe.

“The Rock Hoppers form their rookeries at the foot of high hills, and make their nests of stones and turf. This is the only species of Penguin that whistles; the King Penguins halloo, and the Johnnys and Macaroonys make a sort of yawing noise.

“One kind of bird which proved very valuable to us are called Nellys. They are larger than a goose, and resort to these islands in great numbers. They make burrows in the ground, and were very easily caught. These birds are so ravenous, that after we had killed a Sea-Elephant, they would, in a few hours, completely carry off every particle of flesh we did not make use of, leaving the bones clean as possible. Their young became very good eating in March.”

Although this party knew that the other party of sealers had been left on the larger island, they did not venture to cross to it, as the seas were very rough, and winds were almost always contrary. However, this party on the western island, in December, 1821, finding the seals very scarce, and other provisions scanty, determined on visiting the eastern island, but without the least expectation of finding any remnants of the vessel, much less of meeting any of their comrades, whom they supposed to be all drowned.

They arrived on the 13th December, and entered the same cove where was the residence of those who had escaped the wreck. The joy of all hands on meeting is better conceived than described. The new arrivals had brought with them their kettle, frying-pan, and other implements; and also the discovery they had made that the cabbage growing on the islands if boiled for three or four hours lost its bitterness. This now proved to be a rich delicacy after such long deprivation of vegetable diet.

As the chance of any vessel coming to the Crozets became apparently less and less, the whole party now resolved to attempt to construct a vessel in which to make their escape. Those on the western isle had found there remains of wooden huts, and some beams and planks had been dug up on the eastern isle. It was found that the means of subsistence on that island where the whole party was now settled would not suffice for all. It was accordingly resolved again to separate. Captain Veale and his brother, Goodridge, Soper, and Spesinick, an Italian, were to go to the western isle and remain there, but the timber found there was to be transferred to the eastern isle, where the vessel was to be constructed. This accordingly was effected. Meanwhile Goodridge’s clothes had worn out, and he had to clothe himself in seal-skins.

In building the ship numerous were the difficulties experienced. Tools were few and imperfect. They had neither pitch nor oakum. The rigging was made of the ropes taken on shore by the sealing party wherewith to raft off to the boats the skins procured, as the surf on the beaches prevented their landing to load with safety and convenience.

By the beginning of January, 1823, the vessel was completed by the ten men on the eastern isle, and it was equipped with sails of seal-skins. They also formed vessels for taking a stock of fresh water, from the skins of pup elephants; and they provided a store of salted tongues, eggs, and whatever could be got for a voyage in the frail bark. Then the boat was sent over to the western isle to fetch away those on it to assist in launching the ship; and lots were to be cast as to the five whom alone it would accommodate, and who were to be sent off in this frail vessel, without compass or chart, on the chance of falling in with some ship in the Southern Seas.

Two years had now nearly passed since the party had been wrecked.

Seven had come over to the western isle to summon the Veales, Goodridge, and the rest, but it was not possible to return the same day; and during the night a violent gale of wind sprang up, and the boat having been hauled up in an exposed situation, the wind caught her, carried her to a distance of seventy yards, and so damaged her as to render her unseaworthy, the stern being completely beat in. This disaster produced consternation; for the other boat, that left on the eastern isle, had been ripped up to line the ship that had been constructed.

On the 21st, “about noon, whilst most of us were employed in preparing for our meal, Dominic Spesinick, who was an elderly man, left us to take a walk; he had proceeded to a high point of land about three parts of a mile distant from our hut, and saw a vessel passing round the next point. He immediately came running towards us in great agitation, and for some time could do nothing but gesticulate, excess of joy having completely deprived him of the power of utterance. Capt. Veale, who was with me, asked what the foolish fellow was at, and he having by this time a little recovered himself, told us that he had certainly seen a vessel pass round the point of the island. We had so often been deceived by the appearance of large birds sitting on the water, which we had mistaken for vessels at a distance, that we were slow to believe his story; however, it was agreed that John Soper should go with him, taking a direction across the island, so that they might, if possible, intercept the vessel; and being supplied with a tinder-box, in order to light a fire, to attract the notice of the crew should they gain sight of her, off they started.

“The hours passed very slowly during their absence, and when night approached, and they were not returned, a thousand conjectures were started to account for their stay. Morning at length came, after a tedious night. Some had not closed their eyes, whilst the others who had caught a few minutes sleep had been disturbed by frightful dreams, and wakened only to disappointed hopes.

“Our two companions had been fortunate enough to reach that part of the island in which the vessel was still in sight; and by finding the remains of a sea-elephant that had been recently killed, they ascertained that the crew had been on shore, and they hastened to kindle a fire; but finding they could not attract the attention of those in the vessel from the beach, they proceeded with all haste to ascend a hill in the direction she was still steering. Spesinick, however, became exhausted, and was unable to proceed further. Soper went on, but had to descend into a valley before he could gain another elevated spot to make a signal from. Spesinick, returning to the beach where they had kindled the fire, to his great joy, saw a boat from the vessel coming on shore. The crew had reached the beach before Spesinick got to it; but his voice was drowned by the noise of a rookery of macaroonys he had disturbed on the hill. Seeing the fire, the smoke of which had first attracted their attention, they were convinced that there were human beings on the island, and had commenced a search. In the interim, Spesinick had made for the boat, and having reached it clung to it in a fit of desperate joy that gave him the appearance of a maniac; and the crew, on returning, found him in such questionable guise that they hailed him before approaching. Dressed in shaggy fur skins, with a cap of the same material, and beard of nearly two years’ growth, it was not probable that they should take him for a civilized being. They soon, however, became better acquainted, and he gave them an outline of the shipwreck, the number of men on the island, and that Soper was not far off.

“The vessel proved to be an American schooner called the Philo, Isaac Perceval, master, on a sealing and trading voyage.

“Soper, being still unaware of the boat having gone ashore, as it must have done so, while he was crossing the valley, on coming to a place where, on a foraging excursion, we had erected a shelter at the opening of a cave, he set the place on fire, and the boat which had returned with Spesinick put off and took him on board also, much to his joy. By this time it was nearly dark, and too late to send or make any communication to us on that evening, but on the following morning, 22 January, the captain of the schooner sent his boat to fetch off the remaining ten.

“We had by this time almost given up all hopes of our expected deliverance, and had gone to a neighbouring rookery to gather all the eggs we could collect. Shortly after ten a shout from one of our companions, Millichant, aroused our attention, and we soon perceived the American schooner’s boat coming round the point. Down went the eggs. Some capered, some ran, some shouted, and three loud cheers from us were quickly answered by those in the boat.

“Here I cannot help breaking off in my narrative to remark on the providential nature of our succour. The damage done to our boat had caused us much distress, but now how different were our views of the accident; for had our boat not been damaged, our return to the other island would have followed as a matter of course; and, in all probability, we should never have seen the vessel that now proved the means of our deliverance.”

On 23 January, Captain Perceval steered for the east island, and took off the remainder of the shipwrecked men.

“The day of departure now arrived, and after remaining on those islands one year, ten months, and five days, we bade them adieu—shall I say with great joy? Certainly; and yet I felt a mixture of regret. Whether from the perverseness of my nature, or from any other cause, I can only say—so it was.”

The American captain was bent on collecting seal-skins, and it was his purpose to visit the islands of Amsterdam and St. Paul’s, and then make his way to the Mauritius, where he would leave those whom he had rescued. Meanwhile, he required them, like a shrewd, not to say grasping Yankee, to work for him at the seal fishery; and this they did till the 1st April, when he was at St. Paul’s. There dissatisfaction broke out among those he had rescued. He had kept them working hard for him during two months, and had not given them even a change of clothing. The Italian Mazora spoke out, and Captain Perceval was furious and ordered him to be set on shore; he would take him no further in his ship. At this his comrades in misfortune spoke out also. Having suffered so long together they would not desert a comrade, and they all resented the way in which Captain Perceval was taking an unfair advantage of them. They had, in fact, secured for him five thousand seal-skins and three hundred quintals of fish. The Yankee captain having now got out of them all he could, did not trouble himself about taking them any further, and sent ten of them ashore: only three—Captain Veale, his brother, and Petherbridge—went on with the American ship. Two others, Soper and Newbee, had remained at their own wish at Amsterdam, which they could leave when they wished, as it lay in the direct track of all ships going from the Cape of Good Hope to New South Wales.

The American captain gave a cask of bread and some necessaries to those he put ashore on St. Paul’s.

Here they remained, renewing their hardships on the Crozets, but in a better climate, till the first week in June, when a sloop, a tender to the King George whaler, arrived, looking for her consort in vain. The sloop was only twenty-eight tons and could not accommodate more than three, and the lot decided that Goodridge should be one of these three. Then the sloop sailed for Van Diemen’s Land, and after a rough passage of thirty-six days reached Hobart Town on 7 July.

We need not follow Goodridge’s narrative further, though what remains is interesting: his observations on the condition of the convicts, the settlers, and so forth. He there got into trouble, being arrested and thrown into prison on the suspicion that he was a runaway sailor from the King George, and he had great difficulty in obtaining his discharge. He was also attacked and nearly murdered by bushrangers.

At length, in the beginning of 1831, he was able to start for home. He embarked on 15 February. “On Sunday morning, 31st July, we came off Torbay, and now I anxiously looked out for some conveyance to land: I was in sight of my native village—my heart beat high. The venerable tower of Paignton, forming as it does one of the most conspicuous objects in the bay, was full in view, and with my glass I could trace many well-remembered objects, even the very dwelling of my childhood and the home of my parents.” On 2 August, Goodridge reached home to find his parents still alive, though the old man was infirm and failing. He had been away eleven years; but of these a good many had been spent by him in business in Van Diemen’s Land.