Hals tells the following story of Mr. Edward Chapman, of Constantine. But before giving it, it will be well to say a few words of the Chapman family. The name suffices to show that it was not Cornish by origin, and indeed in the Heralds’ Visitation it is recorded to have come from the North. Why they came down one cannot say, but they married well. One John Chapman, of Harpford, in Devon, had to wife a daughter of Chichester, of Hall, and his son Edward married a Prideaux, and settled at Resprin in S. Winnow, and as that was a manor that belonged to the Prideaux family it is probable that his wife was an heiress. Edward, the grandson, baptized at S. Winnow May 12th, 1647, was probably the person mentioned by Hals, to whom the adventure is attributed. He was married to a daughter of Bligh, of Botathen.

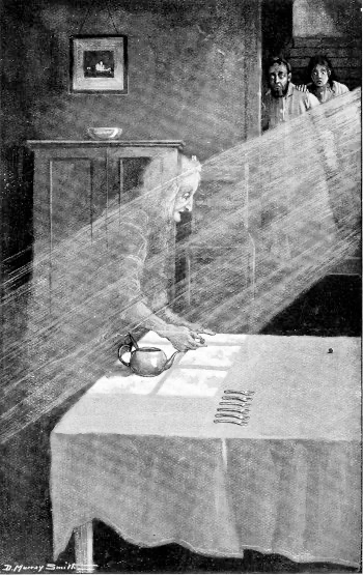

“This gentleman received from God’s holy angels a wonderful preservation in the beginning of the reign of William III when returning from Redruth towards his own house about seven miles distant, with his servant, late at night, and both much intoxicated with liquor (as himself told me); nevertheless having so much sense left as to consider that they were to pass through several tin mines or shafts near the highway, on the south-east side of Redruth town, alighted both from their horses, and led them in their hands after them. The servant went somewhat before his master, the better to keep the right road in those places, which occasioned Mr. Chapman’s turning aside somewhat out of the way, whereby in the dark he suddenly fell into a tin mine above twenty fathoms deep, at whose fall into this precipice his horse started back and escaped; in this pit or hole Mr. Chapman fell directly down fifteen fathoms without let or intermission, where meeting with a cross drift (above six fathoms of water under it), he in his campaign coat, sword, and boots, was miraculously stopped, when, coming to himself, he was not much sensible of any hurt or bruises he had received, through the terror and horror of his fall; when, considering in what condition he was, he resolved to make the best expedient he could to prevent his falling further down (where, by the dropping of stones and earth moved by his fall, he understood there was much water under), so he rested his back against one side of the ruin, and his feet against the other, athwart the hole, and in order to fix his hands on some solid thing, drew his sword out of its sheath, and thrust the blade thereof as far as he could into the opposite part of the shaft, and so in great pain and terror rested himself.

“The suddenness of this accident, and the horse’s escaping in the dark as aforesaid, was the reason why Mr. Chapman’s servant, who went before him, did not so soon find him wanting as otherwise he might, which as soon as he did, he went back the roadway in quest of him, calling him aloud by his name; but receiving no answer, nor being able to find his horse, he concluded his master had rode home some other way, whereupon, giving up all further search after him, he hastened home to Constantine, expecting to have met him there; but contrary to his expectations, found he was not returned. Whereupon his servants, early next morning, went forth to inquire after him, and suspecting (as it happened) he might be fallen into some tin-shafts about Redruth, hastened thither, where, before they arrived, some tinners had taken custody of his horse (with bridle and saddle on), which they found grazing in the Wastsell Downs. Whereupon, consulting together about this tragical mishap, it was resolved forthwith that some of these tinners, for reward, should search the most dangerous shafts in order to find his body, either living or dead; accordingly they employed themselves that day till about four o’clock in the afternoon without any discovery of him. Finally, one person returned to his company, and told them that at a considerable distance he heard a kind of human voice underground; to which place they repaired, and making loud cries to the hole of the shaft, he forthwith answered them that he was there alive, and prayed their assistance in order to deliver him from that tremendous place; whereupon, immediately they set on tackle ropes and windlass on the old shaft, so that a tinner descended to the place where he rested, and having candle-light with him, bound him fast in a rope, and so drew him safely to land, where, to their great admiration and joy, it appeared he had neither broke any bone, or was much bruised by the fall; verifying that old English proverb, that drunkards seldom take hurt; for, as the tinners said, if he had fallen but two or three feet lower, he must inevitably have been drowned in the water. But maugre all these adverse accidents, after about seventeen hours’ stay in the pit aforesaid, he miraculously escaped death, and lived many years after, and would recount this story with as much pleasure as men do the ballads of ‘Chevy Chase’ or ‘Rosamond Clifford.’”