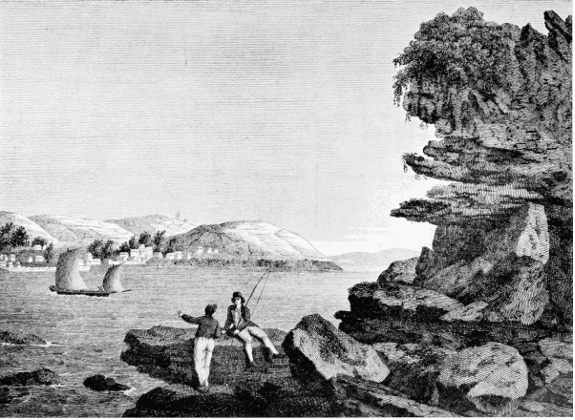

of Beer, Devonshire

“THE ROB ROY of the WEST”

A very noticeable feature of the Devon and Cornwall coasts is the trenched and banked-up paths from the little coves. By these paths the kegs and bales were removed under cover of night.

As an excuse for keeping droves of donkeys, it was pretended that the sea-sand and the kelp served as admirable dressing for the land; and no doubt so they did; the trains of asses sometimes came up laden with sacks of sand, but not infrequently with kegs of brandy.

Now a wary preventive man might watch too narrowly the proceedings of these trains of asses. Accordingly squires, yeomen, farmers alike set to work to cut deep ways in the face of the downs, along the slopes of the hills, and bank them up, so that whole caravans of laden beasts might travel up and down absolutely unseen from the sea and greatly screened from the land side.

Undoubtedly the sunken ways and high banks are a great protection against the weather. So they were represented to be—and no doubt greatly were the good folks commended for their consideration for the beasts and their drivers, in thus at great cost shutting them off from the violence of the gale. Nevertheless, it can hardly be doubted that concealment from the eye of the coastguard was sought by this means quite as much as, if not more than the sheltering the beasts of burden from the weather.

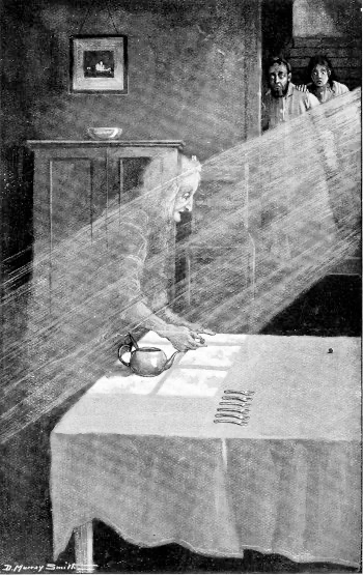

A few years ago, an old church-house in my own parish was demolished. The church-house was originally the place where the parishioners from a distance, in a country district, put up between the morning and afternoon services on the Sunday, and was used for “church ales,” etc. It was always a long building of two stories; that below served for the men, that above for the women, and each had its great fireplace. Here they ate and chattered between services, as already said, and here were served with ale by the sexton or clerk. In a great many cases these church-houses have been converted into taverns. Now this one in the writer’s parish had never been thus altered. When it was pulled down, it was found that the floor of large slate slabs in the lower room was undermined with hollows like graves, only of much larger dimensions—and these had served for the concealment of smuggled spirits. The clerk had, in fact, dug them out, and did a little trade on Sundays with selling contraband liquor from these stores.

The story is told of a certain baronet near Dartmouth, now deceased, who had a handsome house and park near the coast. The preventive men had long suspected that Sir Thomas had done more than wink at the proceedings of the receivers of smuggled goods. His park dipped in graceful undulations to the sea and to a lovely creek, in which was his boathouse. But they never had been able to establish the fact that he favoured the smugglers, and allowed them to use his grounds and outbuildings.

However, at last, one night a party of men with kegs on their shoulders were seen stealing through the park towards the mansion. They were observed also leaving without the kegs. Accordingly, next morning the officer in command called, together with several under lings. He apologized to the baronet for any inconvenience his visit might occasion—he was quite sure that Sir Thomas was ignorant of the use made of his park, his landing-place, even of his house—but there was evidence that “run” goods had been brought to the mansion the preceding night, and it was but the duty of the officer to point this out to Sir Thomas, and ask him to permit a search—which would be conducted with all the delicacy possible. The baronet, an exceedingly urbane man, promptly expressed his readiness to allow house, cellar, attic—every part of his house, and every outbuilding—unreservedly to be searched. He produced his keys. The cellar was, of course, the place where wine and spirits were most likely to be found—let that be explored first. He had a cellar-book, which he produced, and he would be glad if the officer would compare what he found below with his entries in the book. The search was made with some zest, for the Government officers had long looked on Sir Thomas with mistrust; and yet were somewhat disarmed by the frankness with which he met them. They ransacked the mansion from garret to cellar, and every part of the outbuildings, and found nothing. They had omitted to look into the family coach, which was full of rum kegs, so full that, to prevent the springs being broken or showing that the carriage was laden, the axle-trees were “trigged up” below with blocks of wood.

When a train of asses or mules conveyed contraband goods along a road, it was often customary to put stockings over the hoofs to deaden the sound of their steps.

One night many years ago, a friend of the writer—a parson on the north coast of Cornwall—was walking along a lane in his parish at night. It was near midnight. He had been to see, and had been sitting up with, a dying person.

As he came to a branch in the lane he saw a man there, and he called out “Good night.” He then stood still a moment, to consider which lane he should take. Both led to his rectory, but one was somewhat shorter than the other. The shorter was, however, stony and very wet. He chose the longer way, and turned to the right. Thirty years after he was speaking with a parishioner who was ill, when the man said to him suddenly: “Do you remember such and such a night, when you came to the Y? You had been with Nankevill, who was dying.”

“Yes, I do recall something about it.”

“Do you remember you said ‘Good night’ to me?”

“I remember that someone was there; I did not know it was you.”

“And you turned right instead of left?”

“I dare say.”

“If you had taken the left-hand road you would never have seen next morning.”

“Why so?”

“There was a large cargo of ‘run’ goods being transported that night—and you would have met it.”

“What of that?”

“What of that? You would have been chucked over the cliffs.”

“But how could they suppose I would peach?”

“Sir! They’d ha’ took good care you shouldn’t ha’ had the chance!”

The principal ports to which the smugglers ran were Cherbourg and Roscoff; but also to the Channel Islands. During the European War, and when Napoleon had formed, and forced on the humbled nations of Europe, his great scheme for the exclusion of English goods from all ports, our smugglers did a rare business in conveying prohibited English wares to France and returning with smuggled spirits to our shores, reaping a harvest both ways. If a revenue cutter hove in sight and gave chase, they sank their kegs, but with a small buoy above to indicate where they were, and afterwards they would return and “creep” for them with grappling irons. But the preventive officers were on the alert, and although they might find no contraband on the vessel they overhauled, yet the officers threw out their irons and searched the sea in the wake of the ship, and kept a sharp look-out for the buoys. If the contraband articles were brought ashore, and there was no opportunity to remove them at once, they were buried in the sand, to be exhumed when the coast was clear.

The smugglers had more enemies to contend with than the preventive men. As they were known to be daring and experienced sailors, they were in great request to man the navy, and every crib and den was searched for them that they might be impressed.

The life was hard, full of risks, and although these men sometimes made great hauls, yet they as often lost their cargoes and their vessels. They were very frequently in the pay of merchants in England, who provided them with their ships and bailed them out when they were arrested. Rarely did a smuggler realize a competence, he almost invariably ended his days in poverty. One of the most notorious of the Devon free-traders was Jack Rattenbury, who was commonly called “The Rob-Roy of the West.” He wrote his Memoirs when advanced in life, and when he had given up smuggling, not that the trade had lost its attraction for him, but because he suffered from gout, and he ended his days as a contractor for blue-lias lime for the harbour in course of erection at Sidmouth.

It will not be necessary to give the life of this man in full. It was divided into two periods—his career on a privateer and his career as a smuggler—spent partly in fishing, partly as a pilot, mainly in carrying on free trade in spirits, between Cherbourg, or the Channel Islands, and Devon. Naturally, Rattenbury speaks of himself and his comrades as all honourable men, it is the informers who are the spawn of hell. The record year by year of his exploits as a smuggler, presents little variety, and the same may be said of his deeds as a privateer. We shall therefore give but a few instances illustrative of his career in both epochs of his life.

John Rattenbury was born at Beer in the year 1778. Beer lies in a cleft of the chalk hills, and consists of one long street of cottages from the small harbour. His father was a shoemaker, but tired of his awl and leather apron, he cast both aside and went on board a man-of-war before John was born, and was never heard of more. It is possible that Mrs. Rattenbury’s tongue may have been the stimulating cause of his desertion of the last.

The mother of John, frugal and industrious, sold fish for her support and that of her child, and contrived to maintain herself and him without seeking parish relief. The boy naturally took to the water, as all the men of Beer were fishermen or smugglers, and at the age of nine he went in the boat with his uncle after fish, but happening one day when left in charge to lose the rudder of the row-boat, his uncle gave him the rope’s end so severely that the boy ran away and went as apprentice to a Brixham fisherman; but this man also beat and otherwise maltreated him, and again he ran away. As he could get no employment at Beer, he went to Bridport and engaged on board a vessel in the coasting trade. But he did not remain long with his master and returned to Beer, where he found his uncle entering men for privateering, and this fired John Rattenbury’s ambition and he volunteered.

“About the latter end of March, 1792, we proceeded on our first cruise off the Western Islands: and even now, notwithstanding the lapse of years, I can recall the triumph and exultation which rushed through my veins as I saw the shores of my native land recede, and the vast ocean opening before me.”

Instead of making prizes, the privateer and her crew were made a prize of and conveyed to Bordeaux, where the crew were detained as prisoners. John Rattenbury, however, contrived to make his escape to an American vessel lying in the harbour, on which, after detention for twelve months, he sailed to New York. There he entered on an American vessel bound for Copenhagen, and on reaching that place invested all the money he had earned and carried away with him from Bordeaux in fiddles and clothes. Then he sailed in another American vessel for Guernsey, where he profitably disposed of his fiddles and clothes. He had engaged with the captain for the whole voyage to New York, but when at Guernsey at his request the captain allowed him to return to England to visit his family, on passing his word that he would rejoin the ship within a specified time. Rattenbury returned to Beer, and broke his promise, which he regards as a mistake. He remained at home six months occupied in fishing, “but,” says he, “I found the employment very dull and tiresome after the roving life I had led; and as the smuggling trade was then plied very briskly in the neighbourhood, I determined to try my fortune in it.” Fortune in smuggling as in gambling favours beginners so as to lure them on. However, after a few months, Rattenbury had lapses into the paths of honesty. In one of these, soon after, he did one of the most brilliant achievements of his life. I will give it in his own words:—

“Being in want of a situation, I applied to Captain Jarvis, and agreed to go with him in a vessel called the Friends, which belonged to Beer and Seaton. As soon as she was rigged we proceeded to sea, but, contrary winds coming on, we were obliged to put into Lyme; the next day, the wind being favourable, we put to sea again, and proceeded to Tenby, where we were bound for culm. At eight o’clock the captain set the watch, and it was my turn to remain below; at twelve I went on deck and counted till four, when I went below again, but was scarcely dropped asleep, when I was aroused by hearing the captain exclaim, ‘Come on deck, my good fellow! Here is a privateer, and we shall all be taken.’ When I got up, I found the privateer close alongside of us. The captain hailed us in English, and asked us from what port we came and where we were bound. Our captain told the exact truth, and he then sent a boat with an officer in her to take all hands on board his own vessel, which he did, except myself and a little boy, who had never been to sea before. He then sent the prize-master and four men on board our brig, with orders to take her into the nearest French port. When the privateer was gone, the prize-master ordered me to go aloft and loose the maintop-gallant sail. When I came down, I perceived that he was steering very wildly through ignorance of the coast, and I offered to take the helm, to which he consented, and directed me to steer south-east by south. He went below, and was engaged in drinking and carousing with his companions. They likewise sent me up a glass of grog occasionally which animated my spirits, and I began to conceive a hope not only of escaping, but also of being revenged on the enemy. A fog too came on, which befriended the design I had in view; I therefore altered the course to east by north, expecting that we might fall in with some English vessel. As the day advanced the fog gradually dispersed, and, the sky getting clearer, we could perceive land; the prize-master and his companions asked me what land it was; I told them that it was Alderney, which they believed, though at the same time we were just off Portland. We then hauled our wind more to the south until we cleared the Bill; soon after we came in sight of land off St. Alban’s: the prize-master then again asked what land it was which we saw; I told him it was Cape La Hogue. My companions then became suspicious and angry, thinking I had deceived them, and they took a dog that had belonged to our captain, and threw him overboard in a great rage and knocked down his house. This was done as a caution to intimate to me what would be my fate if I had deceived them. We were now within a league of Swanage, and I persuaded them to go on shore to get a pilot: they then hoisted out a boat, into which I got with three of them, not without serious apprehension as to what would be the event. We now came so near the shore that the people hailed us, and told them to keep further west. My companions began to swear, and said the people spoke English: this I denied, and urged them to hail again; but as they were rising to do so, I plunged overboard and came up the other side of the boat; they then struck at me with their oars, and snapped a pistol at me, but it missed fire. I still continued swimming, and every time they attempted to strike me, I made a dive and disappeared. The boat in which they were now took water, and finding they were engaged in a vain pursuit, and endangering their own safety, they suddenly turned round, and rowed away as fast as possible to regain the vessel. Having got rid of my foes, I put forth all my efforts to get to the shore, which I at last accomplished. In the meantime, the men in the boat reached the brig, and spreading all canvas, bore away for the French coast. Being afraid they would get off with the vessel, I immediately sent two men, one to the signal-house at St. Alban’s and another to Swanage, to obtain all the assistance they could to bring her back.

“Fortunately, there was at the time in Swanage Bay a small cutter, belonging to His Majesty’s customs, called the Nancy, commanded by Captain Willis; and as soon as he had received the information, he made all sail after them; but I was not on board, not being able to reach them in time. The cutter came up with the brig, and by retaking, brought her into Cowes the same night, where the men were put in prison. Captain Willis then sent me a letter, stating what he had done, and advising me to go as quickly as possible to the owners, and inform them of all that had taken place. This I did without delay, and one of them immediately set off for Cowes, when he got her back by paying salvage—but I never received any reward for the service I had rendered, either from the owners or from any other quarter.”

John Rattenbury was then aged sixteen.

As Rattenbury was returning to Devon in a cutter, the vessel was stopped and overhauled by a lieutenant and his gang seeking able-bodied seamen to impress them.

“When it came to my turn to be examined, I told him I was an apprentice, and that my name was German Phillips (that being the name of a young man whose indenture I had for a protection). This stratagem was of no avail with the keen-eyed lieutenant, and he took me immediately on board the Royal William, a guard ship, then lying at Spithead. I remained in close confinement for a month, hoping by some chance I might be able to effect my escape; but seeing no prospect of accomplishing my design, I at last volunteered my services for the Royal Navy; if that can be called a voluntary act, which is the effect of necessity, not of inclination.

“And here I cannot help making a remark on the common practice of impressing seamen in time of war. Our country is called the land of liberty; we possess a just and invincible aversion to slavery at home and in our foreign colonies, and it is triumphantly said that a slave cannot breathe in England. Yet how is this to be reconciled with the practice of tearing men from their weeping and afflicted families, and from the peaceable and useful pursuits of merchandise and commerce, and chaining them to a situation which is alike repugnant to their feelings and their principles?”

At Spithead Rattenbury succeeded in making his escape. But he had left his pocket-book on board, and by this means the lieutenant found out what were his real name and abode, and thenceforth he was hunted as a deserter and put to great shifts to save himself from capture.

In 1800, when he was twenty-one, he was taken in a vessel by a Spanish privateer and brought to Vigo; but on shore made himself so useful and was so cheerful that he was given his liberty and travelled on foot to Oporto, where he found a vessel bound for Guernsey, laden with oranges and lemons, and worked his way home in her.

“Before I set out on my last voyage, I had fixed my affections on a young woman in the neighbourhood, and we were married on the 17th of April, 1801. We then went to reside at Lyme, and finding that I could not obtain any regular employment at home, I again determined to try my fortune in privateering, and accordingly engaged myself with Captain Diamond of the Alert.”

But this expedition led to no results. No captures were made, and Rattenbury returned home as poor as when he started, and almost at once acted as pilot to foreign vessels. On one occasion a lieutenant came on board to impress men, and took Rattenbury and put him in confinement. Next day he told the lieutenant that if he would accompany him to Lyme, he would show him a public-house where he was sure to find men whom he could impress. The officer consented and landed with Jack and some other seamen, and proceeded to the tavern; but finding none there he ordered Rattenbury back to the boat. At that moment up came Rattenbury’s wife, and he made a rush to escape whilst she threw herself upon the lieutenant and had a scuffle with him; and as the townfolk took her part, Rattenbury managed to escape.

On another occasion he was at Weymouth, and the same lieutenant, learning this fact, tracked him to the tavern where he slept, and burst in at 2 a.m. Rattenbury had just time to climb up the chimney before the officer and his men entered. They searched the house, but could not find him. When they were gone he descended much bruised, half-stifled, and covered with soot.

“Wearied out by the incessant pursuit of my enemies, and finding that I was followed by them from place to place like a hunted stag by the hounds, I at last determined, with a view to getting rid of them, again to go privateering.” Accordingly he shipped on board the Unity cutter and cruised about Madeira and Teneriffe, looking out for prizes. But this expedition was as unsuccessful as the other, and in August, 1805, he returned home; “and I determined never again to engage in privateering, a resolution which I have ever since kept, and of which I have never repented.”

We now enter on the second period of Rattenbury’s career.

“On my return home, I engaged ostensibly in the trade of fishing, but in reality was principally employed in that of smuggling. My first voyage was to Christchurch, in an open boat, where we took in a cargo of contraband goods, and, on our return, safely landed the whole.

“Being elated with this success, we immediately proceeded to the same port again, but on our way we fell in with the Roebuck tender: a warm chase ensued; and, in firing at us, a man named Slaughter, on board the tender, had the misfortune to blow his arm off. Eventually, the enemy came up with and captured us; and, on being taken on board, found the captain in a great rage in consequence of the accident, and he swore he would put us all on board a man-of-war. He got his boat out to take the wounded man on shore; and, while this was going forward, I watched an opportunity, and stowed myself away in her, unknown to any person there. I remained without being perceived, amidst the confusion that prevailed; and when they reached the shore, I left the boat, and got clear off. The same night, I went in a boat that I had borrowed, alongside the tender, and rescued all my companions; we likewise brought three kegs of gin away with us, and landed safe at Weymouth, from whence we made the best of our way home.

“The same winter I made seven voyages in a smuggling vessel which had just been built; five of them were attended with success, and two of them turned out failures.

“In the spring of 1806, I went to Alderney, where we took in a cargo; but, returning, fell in with the Duke of York cutter, in consequence of getting too near her boat in a fog without perceiving her. Being unable to make our escape, we were immediately put on board the cutter, and the crew picked up some of our kegs which were floating near by, but we had previously sunk the principal part. As soon as we were secured, the captain called us into his cabin, and told us that if we would take up the kegs for him, he would give us our boat and liberty, on the honour of a gentleman. To this proposal we agreed, and having pointed out where they lay, we took them up for him. We then expected that the captain would have been as good as his word; but, instead of doing so, he disgracefully departed from it, and a fresh breeze springing up, we steered away hard for Dartmouth. When we came alongside the castle, the cutter being then going at the rate of 6 knots, I jumped overboard; but having a boat in her stern, they immediately lowered her with a man. I succeeded, however, in getting on shore, and concealed myself among some bushes; but two women who saw me go into the thicket inadvertently told the boat’s crew where I was, upon which they retook me, and I was carried on board quite exhausted with the fatigue and loss of blood, for I had cut myself in different places.”

Next morning Rattenbury was brought up before the magistrates at Dartmouth along with his comrades in misfortune, and they were sentenced to pay a fine of a hundred pounds each, or else to serve on board a man-of-war, or go to prison. They elected the last, and were confined in a wretched den where they could hardly move and breathe. Worn out by their discomfort, they agreed to enlist, and were liberated and removed to a brig in Dartmouth roads. On coming on board he found all the officers drinking, and that the mainsail had been partly hoisted so that the officers could not command a prospect of the shore. Seizing his opportunity he jumped overboard, and seeing a boat approaching held up his hand to the man in it, as a signal to be taken up. The fellow did so, and in less than five minutes he was landed at Kingswear, opposite Dartmouth. He paid the fisherman a pound, and made his way to Brixham, where he hired a fishing-smack and got safely home.

Soon after he purchased part of a galley, and resumed his smuggling expeditions, and made several successful trips in her, till he lost his galley at sea. Then he went to Alderney in an open boat, with two other men, to get kegs, but on their way back were chased, captured, and carried into Falmouth, where he was sentenced to be sent to gaol at Bodmin.

“We were put into two post-chaises, with two constables to take care of us. As our guards stopped at almost every public-house, towards evening they became pretty merry. When we came to the ‘Indian Queen’—a public-house a few miles from Bodmin—while the constables were taking their potations, I bribed the drivers not to interfere. Having finished, the constables ordered us again into the chaise, but we refused. A scuffle ensued. One of them collared me, some blows were exchanged, and he fired a pistol, the ball of which went close to my head. My companion in the meantime was encountering the other constable, and he called on the drivers to assist, but they said it was their duty to attend the horses. We soon got the upper hand of our opponents, and seeing a cottage near, I ran towards it, and the woman who occupied it was so kind as to show me through her house into the garden and to point out the road.”

Eventually he reached Newquay with his comrade. Thence they hired horses to Mevagissey, where they took a boat for Budleigh Salterton. On the following day they walked to Beer.

This is but a sample of one year out of many. He was usually engaged in shady operations, getting him into trouble. On one occasion he undertook to carry four French officers across the Channel who had made their escape from the prison at Tiverton, for the sum of a hundred pounds, but was caught, and narrowly escaped severe punishment. Soon after that he was arrested as a deserter, by a lieutenant of the sea-fencibles when he was in a public-house drinking along with a sergeant and some privates. But he broke away and jumped into the cellar, where he divested himself of shirt and jacket, armed himself with a reaping-hook, and closing the lower part of a half-hatch door stood at bay, vowing he would reap down the first man who ventured to attack him. His appearance was so formidable, his resolution was so well known, that the soldiers, ten in number, hesitated. As they stood doubtful as to what to do, some women ran into the house crying out that a vessel had drifted ashore, and a boy was in danger of being drowned, that help was urgently needed. This attracted the attention of the soldiers, and whilst they were discussing what was to be done, Rattenbury leaped over the hatch, dashed through the midst of them, and being without jacket and shirt slipped between their fingers. He ran to the beach, jumped into a boat, got on board his vessel, and hoisted the colours. The story told by the women was a device to distract the attention of his assailants. The lieutenant was furious, especially at seeing the colours flying, as a sign of triumph on the part of Rattenbury, who spread sail and scudded away to Alderney, took in a cargo of contraband spirits, and returned safely with it.

Occasionally, to give fresh zest to his lawless transactions, he did an honest day’s work, as when he piloted safely into harbour a transport vessel that was in danger. We need not follow him through a succession of hair’s-breadth escapes, of successes and losses, imprisonments and frauds. He carries on his story to 1836, when, so little had he profited by his free-trading expeditions, that he was fain to accept a pension from Lord Rolle of a shilling a week.

NOTE.—There is an article by Mr. Maxwell Adams on “Jack Rattenbury” in Snell’s Memorials of Old Devonshire.